BOSTON (Reuters) - Headwinds from China and the world's commodity markets may once again be upending the U.S. Federal Reserve's plans less than a month into its first-in-a-decade tightening cycle.

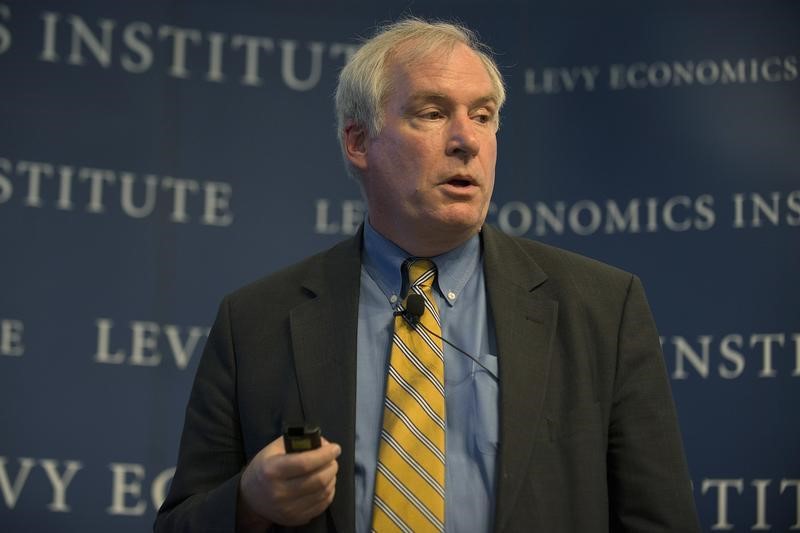

The rout in China's stock market, weak oil prices and other factors are "furthering the concern that global growth has slowed significantly," Boston Fed President Eric Rosengren said on Wednesday.

Rosengren, who votes on the Fed's rate-setting committee this year, also said a second hike will face a strict test as the Fed looks for tangible evidence that U.S. growth will be "at or above potential" and inflation is moving back up toward the Fed's 2 percent target.

When the Fed raised rates by a quarter point in December, policymakers in general forecast four further rate hikes this year.

But since then a marked drop in China's stock market and the yuan, a stubbornly strong dollar and a further decline in oil prices to near 12-year lows have presented a recurrence of challenges the Fed hoped it had left behind last autumn.

The Fed delayed an initial interest rate rise last September when a market sell-off in China triggered a fall in U.S. stocks.

U.S. equity markets, buffeted by renewed volatility, largely looked past last Friday's stellar jobs report. The Commerce Department will also likely report later this month that domestic growth in the fourth quarter slowed, which could further add to jitters.

Investors currently think the Fed will raise rates again in April, according to an analysis of fed funds futures contracts compiled by the CME Group (O:CME).

On Monday, Atlanta Fed president Dennis Lockhart said he did not think there would be enough new data to make a decision on a second hike until at least April, in part because of China's effect on U.S. equity markets.

Robert Kaplan, the Dallas Fed's new president, also cautioned that four interest-rate hikes are "not baked into the cake" given global stock market volatility set off by fears over a cooling Chinese economy.

"This is an unusual start to the year, obviously," Kaplan said on Monday.

While Kaplan thought there might be enough economic data to hand by March to decide whether to raise rates again, "there's no substitute for time in assessing economic data as it unfolds," he said.

The Fed upgraded language in its December policy statement to reflect its desire to see more certainty inflation would trend upwards. Any slowing in domestic growth would hamper this.

Lockhart said he wanted "hard evidence" on a rise in inflation and another Fed policymaker, Chicago Fed president Charles Evans, said last Thursday that it would be mid-year before the Fed would be able to accurately gauge if inflation was moving up.

And while the Fed should not overreact to short-term temporary fluctuations in financial markets, policymakers should take seriously the potential downside risk to their forecasts, Rosengren cautioned.

"These downside risks reflect continued headwinds from weakness within countries that represent many of our major trading partners and only limited data to support the projected path of inflation to target," he said.

The Fed holds the first of its scheduled eight policy meetings this year on Jan. 26-27.