By Stephanie Kelly

LAKE CHARLES, La. (Reuters) - Storm-weary coastal Louisiana residents who fled from the path of Hurricane Delta in recent days streamed back to their homes on Sunday to face cleanup and repairs from the second hurricane to batter their state over the past six weeks.

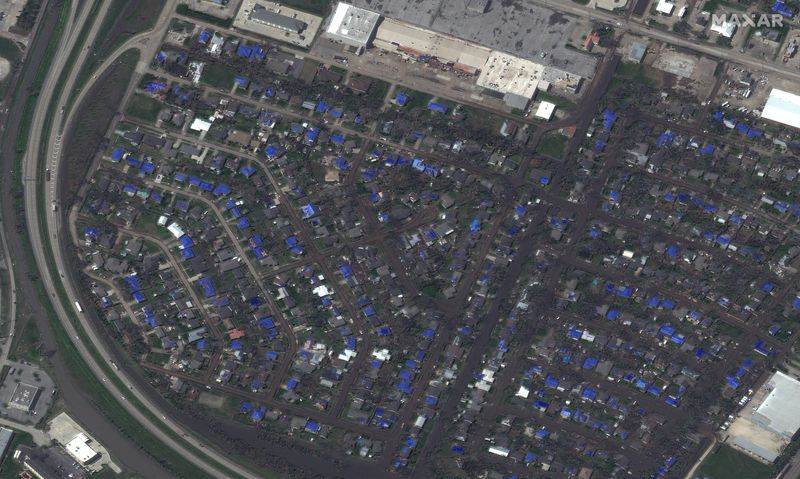

Many returned to find that Delta, dissipating substantially as it drifted farther inland on Sunday, had ripped away temporary tarpaulin roofs installed over their homes in late August after Hurricane Laura, a more powerful storm, struck with devastating force.

Delta, the 10th named storm of the 2020 Atlantic hurricane season to make U.S. landfall, churned ashore on Friday evening near the southwestern Louisiana town of Creole as a Category 2 hurricane on the five-step Saffir-Simpson intensity scale, packing maximum sustained winds of 100 miles per hour (160 kph).

By Sunday, the storm had been downgraded to a post-tropical cyclone over the southern Appalachians, but still posed a heavy rainfall threat, the U.S. National Hurricane Center said.

U.S. energy workers headed back to offshore oil and gas platforms in the northern Gulf of Mexico to restart production that was largely halted as Hurricane Delta barreled into the region, with 91% of crude oil output remaining off-line on Sunday, according to federal regulators.

Governor John Bel Edwards reported the first storm-related death from Delta, an 86-year-old man killed by a fire that started from the refueling of a generator.

"If you are using a generator, please be safe," Edwards warned on Twitter, noting that most deaths from Hurricane Laura stemmed from improper usage of such equipment.

SWELTERING HEAT ADDS TO STORM MISERY

Delta knocked out power to more than 600,000 homes and businesses, but electricity had been restored by Sunday to about half those customers, Edwards told a news conference. The power outages appeared to be a factor in the pace of evacuees returning home.

As of Sunday morning, more than 9,100 Louisianans were still in emergency shelters or other temporary housing, most of them in hotels or at a "mega" shelter set up in the city of Alexandria, according to Catherine Heitman, spokeswoman for the Department of Children and Family Services.

The misery index for returning evacuees was compounded by extreme heat and humidity engulfing southern Louisiana following Delta, and the discovery of property damage made worse by the latest storm.

Lake Charles resident Gerard Meschwitz, 62, who fled to Houston last week, came home on Sunday morning to find that Delta's winds had torn apart some sections of his roof that had been left intact by Laura.

Others braved the hurricane at home only to decide after it passed that the sweltering weather was now too much to bear without air conditioning or a fan.

"I don't see any electricity coming back anytime soon, so I'm going to give them about a week and then come back," said Sam Jones, 77, a Lake Charles resident who rode out the hurricane at home and was heading to his son's home in Fort Worth, Texas.

"When you can't put any air on, it puts you to where you don't get a good night sleep," said Jones, who only recently had power restored to his own home after Laura.

A neighbor who did evacuate came back on Saturday to grab some essentials before leaving again because she was also without power.

New Orleans was housing evacuees in its hotels as Louisiana's largest city was largely unimpaired by the hurricane, said Kelly Schulz, a representative for an organization that promotes tourism there.

Insured losses from Delta were projected to run to $2 billion, while Laura's losses were estimated at around $10 billion, including over $2 billion to offshore energy production facilities, said Steve Bennett, chief product officer for the Demex Group, a technology company.

Insured losses from natural catastrophes have been rising steadily over the past several decades, as a result of climate change and population growth, Bennett said.