By Kole Casule and Angel Krasimirov

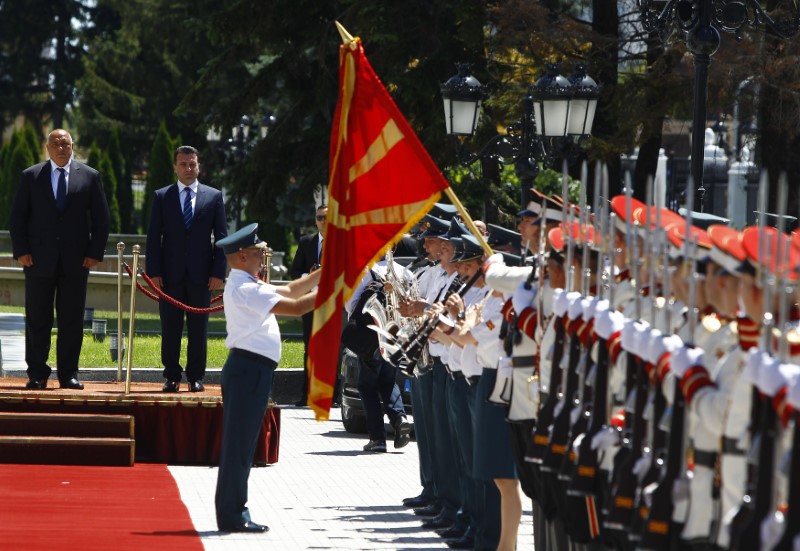

SKOPJE/SOFIA (Reuters) - Macedonian Prime Minister Zoran Zaev and his Bulgarian counterpart Boyko Borissov signed a friendship treaty on Tuesday in a move designed to end years of diplomatic wrangling and boost Macedonia's European integration.

Macedonia’s difficult relations with its bigger eastern neighbor, with which it shares close religious, historic and linguistic ties, have hampered Skopje’s efforts to join NATO and the European Union. Bulgaria belongs to both organizations.

Bulgaria still does not recognize the Macedonian language, which it views as a dialect of Bulgarian.

The two Balkan nations have also clashed over minority rights and the nationality of 19th century guerrillas who fought to free the region from Ottoman Turkish rule.

Both Skopje and Sofia hope the new treaty will help them set aside such differences.

"(This is a) joint contribution to political stabilization between the two countries and in the region," Zaev told reporters after the signing.

Macedonia, a small ex-Yugoslav republic of about 2 million, gained independence from Belgrade in 1991. It avoided the bloody Balkan wars of the 1990s, but was rocked by an insurgency of its large ethnic Albanian minority in 2001.

Skopje wants to join the EU and NATO but its efforts are blocked by its southern neighbor Greece, which says the name 'Macedonia' implies a territorial claim to its own northern province of the same name.

In the document Bulgaria pledged to support Macedonia's NATO and EU integration. The two countries said they would also improve economic ties, renounce territorial claims and improve human and minority rights.

"For the first time, without mediators or somebody telling us what to do, the two states came to a solution," said Bulgaria's prime minister Borissov.

Last week, the Bulgarian parliament unanimously supported the treaty in a rare case of such consensus in the Black Sea country of 7.1 million people.

However, parts of the document that address national issues were opposed by Macedonia's opposition and the former ruling party, the rightist VMRO-DPMNE, which said it would not support it in parliament.

The treaty also acknowledges the shared history of the two countries and their right to taking a different view of some topics.

"In politics and international law there is no such thing as the recognition of history ... Let historians deal with history," Daniel Smilov, an analyst with Bulgaria's Center for Liberal Strategies, told Reuters.