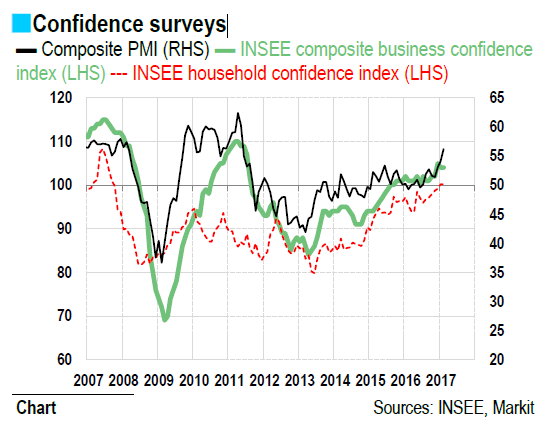

■ The latest confidence surveys are encouraging and point to another quarter of strong growth, estimated at about 0.4% q/q in first-quarter 2017.

■ The European Commission’s latest in-depth review is more mixed as it highlights the limited progress that has been made in terms of structural imbalances.

■ Cost-competitiveness is improving, but the same cannot be said for non-cost competitiveness. The fiscal deficit is narrowing, but not the public debt ratio. The jobless rate has begun to decline, but not long-term unemployment.

From a cyclical perspective, the French economy is looking more upbeat. Granted the improvements have not been clear cut or strong, and the economy continues to be at the risk of major headwinds. Growth still lacks momentum and this year’s acceleration is expected to be mild (1.3% according to our estimates vs. 1.1% in 2016, adjusted for the number of working days). Nonetheless, the most recent indicators are encouraging. The INSEE composite business sentiment index levelled off at 104 in February, the highest level since 2011, and well above the benchmark average of 100. We forecast a quarterly growth rate of 0.4%. Yet given the strong business climate, growth could be stronger, marking an acceleration with regard to fourth-quarter 2016. Indeed, the January-February average of the INSEE index is one point higher than its average level in the fourth quarter. This positive signal is also bolstered by the Markit PMI indices (the composite index hit 56.2 in February, which is also the highest level since 2011) and by the upturn in household confidence (at its highest level since 2007, see chart).

From a structural perspective, in contrast, the situation is still deteriorated according to the European Commission’s latest in-depth annual review. Although some progress has been made, it remains limited in scope compared to the imbalances that need to be corrected. Export market shares have stopped declining since 2012, and cost-competitiveness is in the process of improving, thanks notably to the cuts in employers’ contributions that lower the cost of labour. But France still faces a long road ahead before it regains lost market shares and sustainably reduces the trade deficit. This task will be even harder given the weak productivity gains. The level of investment is considered as satisfactory but not its characteristics (concentrated around a limited number of large firms; in subsectors of declining importance; with little technological progress embedded). As to the business environment, companies are still strapped with high taxation, heavy regulatory restrictions (despite government efforts to reduce and simplify red tape), and an unstable legal framework. Improvements still need to be made in terms of non-cost competitiveness.

As to public finances, the fiscal deficit should drop below the 3% threshold this year. But the Commission highlights the slow pace of the adjustment, and raises questions about the sustainability of deficit reduction. Recently the deficit was reduced mainly through lower interest rates and cutbacks in public investment. It is unlikely that interest rates will remain this low ad vitam aeternam, and France’s growth potential is likely to be hurt by any further cuts in public investment. Under these conditions, how can the deficit be reduced in line with recommendations? Tax revenues already make up a big share of GDP (53.5% in 2015), leaving little leeway for further tax increases. The solution would be to reduce the weight of other spending (excluding debt servicing and public investment), which is also very high (51.4% of GDP in 2015, 57% all expenses combined). For the Commission, the spending savings would have to be big in order to manage to lower the public debt ratio, which is elevated (estimated at 96.4% in 2016) and still rising.

As to the job market, the good news is that the unemployment rate has finally begun to decline after peaking in 2015. Yet compared to the Eurozone (where unemployment started to fall in 2013), this decline has occurred much later and more slowly: the French unemployment rate has shed half a point, compared to a full point for the Eurozone over the same period. As a result, the two jobless rates are now at the same level, at slightly below 10% according to Eurostat data, which remains high. Moreover, long-term unemployment continues to rise in France. In terms of reforms, the El Khomri labour law has been adopted, resulting in a series of measures that makes it easier for companies to adjust, which should help remedy certain job market rigidities. In contrast, the renegotiation of the unemployment insurance scheme did not come to a successful conclusion, nor, as a consequence, the problem of job market segmentation been addressed. This problem is indeed increased by some modalities of the system that contribute to favour the succession of very short periods of work. From this rapid overview of the French economy’s macroeconomic imbalances, we can see the formidable task that awaits France’s next president.

by Hélène BAUDCHON