Economic Commentary

Easier Monetary Policy Offers EMs Some Respite

The world is awash with monetary stimulus. The Bank of Japan (BoJ) is the latest central bank expected to ease monetary policy following the disappointing second quarter growth of just 0.2%. The BoJ joins fellow central banks in the Euro Area and the UK who are also expected to ease later this year. And while the US Federal Reserve (Fed) might still raise rates once by the end of 2016, this is well short of the four rate hikes anticipated at the beginning of the year. Looser monetary policy by the world’s major central banks is driving bond yields in advanced economies to historic lows. This, in turn, is easing the strains on emerging markets (EMs), which have been in thrall to sizeable capital flows since the global financial crisis. EMs should use the opportunity to reduce their fragilities and lower the risk of being at the mercy of fickle foreign capital.

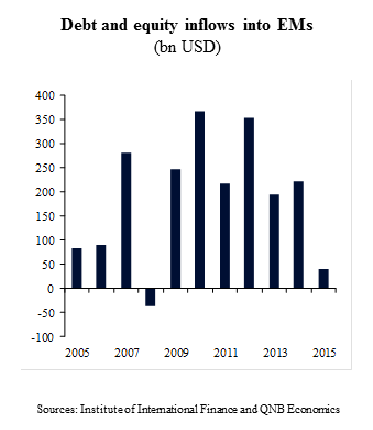

Much like today, foreign capital flocked to EMs in the aftermath of the global financial crisis in 2008. As the crisis hit advanced economies, their central banks responded aggressively by lowering interest rates and engaging in multiple rounds of quantitative easing. The intervention led to a compression of yields. For example, yields on 10-Year US government bonds nearly halved from an average of 3.7% in 2008 to 1.8% in 2012. In response, investors shifted their assets towards EMs in search of higher return. Portfolio inflows into EM debt and equity markets averaged USD296bn per year between 2009 and 2012, compared with USD151bn of annual inflows in the three years prior to 2008.

EMs became more dependent on foreign capital to finance consumption and investment. External debt increased as EM borrowers sought to take advantage of lower interest rates in advanced economies. Capital inflows resulted in asset price appreciation in many EM countries and created a dilemma for policymakers. To cool asset prices, policymakers needed to raise interest rates. But higher rates would have attracted more foreign capital hungry for yield, resulting in further appreciation of asset prices.

Debt and equity inflows into EMs (bn USD)

Sources: Institute of International Finance and QNB Economics

This set the seeds for a crisis which erupted in May 2013 following comments by the Fed that it might taper the size of its QE, resulting in a sharp reversal of the conditions prevailing for the past four years. US bond yields increased from 1.6% in May 2013 to 3.0% by year end. This began a period of capital flight from EMs towards advanced economies and exposed EM vulnerabilities. The crisis was exacerbated by the decline in commodity prices (since many EMs are commodity exporters) and worries about a disorderly slowdown in China. The issues seemed to intensify in the second half of 2015 and the first two months of 2016 as the Fed finally increased interest rates and promised to continue raising rates in the coming months. By early 2016, EMs seemed in an even worse position than 2013 given their worse current account balance, higher external debt and slower GDP growth.

But prospects changed completely around mid-2016. The Brexit vote led to a material slowdown in the UK economy, and the Bank of England responded by cutting rates and restarting its QE programme, with further easing anticipated this year. The European Central Bank and the BoJ are also expected to loosen policy later this year as their economies have stalled. The major liquidity injection by central banks in advanced economies is sinking bond yields to historic lows (1.5% in the US, -0.1% in Germany and 0.5% in the UK). It is now estimated that the value of negative-yielding bonds have risen to USD13.4tn, mainly concentrated in advanced economies. This new environment is making EMs attractive to investors again. Foreign capital is flowing back into EMs, giving them some respite.

EMs should use this opportunity to reduce vulnerabilities and avoid repeating the mistakes of the recent past. This means three things. First, avoid excessive borrowing in foreign currency, which could become harder to service in the event of capital flight and sharp depreciation of the local currency. Second, reserves should be boosted in periods of capital inflows in order to cushion the shock of sudden capital outflow. Finally, EMs should try to alter the composition of foreign capital flowing in. They should encourage more foreign direct investment at the expense of portfolio inflows. The former is stickier, less susceptible to sudden changes in sentiment and generates more sustainable growth rather than merely overheating asset prices. These measures offer an important avenue to prevent a repeat of recent crises.