Another great game is certainly afoot in global financial markets, and China has announced its presence with authority. The bout, of course, is the currency war.

On August 11, China devalued its currency by the largest amount in one day since 1993. By doing so, it joined a phalanx of countries around the world that have actively depreciated their currencies against the U.S. dollar.

Markets have been roiling ever since. This is especially true for commodities, which are already in a weakened position.

But all the drama seems to be a bit of an overreaction.

It’s a Small Move, Really

Politicians who like to blame China for our country’s ills immediately got fired up after the devaluation. New York Senator Charles Schumer began the old song and dance about China artificially keeping the value of its currency too low.

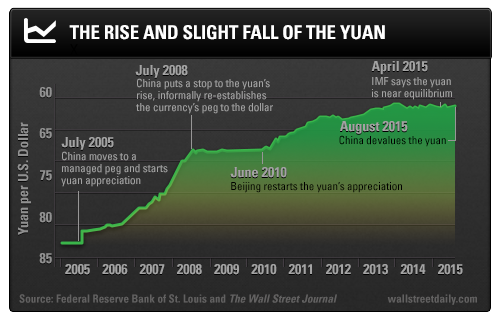

But he seems to have missed the fact that the yuan has been on an upward path for the better part of a decade.

The Bank for International Settlements says that, since the start of 2014, the yuan appreciated 10.3% on average versus all currencies.

Over the course of three days, China pushed down the value of its currency by only about 3.5%. That’s a minor adjustment compared to the vast appreciation of its currency – which has been pegged loosely to the dollar.

Compared to the Japanese yen, the yuan has made much bigger strides – it appreciated by about 80% compared to the yen over the past two years. No one is talking about the other emerging markets, either. Brazil’s currency, the real, fell about 60% against the dollar since 2011.

If China was truly interested in devaluing its currency to boost exports, it would have taken a much more dramatic step, like a 20% to 30% immediate devaluation.

That’s quite unlikely to happen.

Many of China’s companies have lots of dollar-denominated debt. A sharply lower yuan would only add to these firms’ burdens.

|

China’s decision to devalue the yuan reverberated across financial markets. Indeed, the first shots in what could devolve into a global currency war have now been fired.Commodities markets suffered as a result, but this is just a short-term reaction. The longer-term – and more significant – concern is two-fold. First, demand for oil and other natural resources is in peril. Global growth is slowing, and that has profound implications for asset values across the board. Second, the escalating global currency war has us spiraling toward “rancor and conflict,” as one Business Insider author put it. Here’s the bottom line: If you’re at all concerned about the state of the global economy, America’s position within it, and the potential vulnerability of your portfolio, you must listen to what Alan Gula has to say about the next major crisis, its root causes, and a strategy to protect your assets. |

Commodities Crumble

The markets’ reaction to China’s move says more about the state of the markets than it does about the magnitude of China’s action. Especially the commodities sector.

In the commodities world, the mood was already sour, and China’s devaluation only added to that.

You see, a weaker Chinese currency makes commodities, which are priced in dollars, more expensive to buy.

Take oil, for instance. China was expected to account for 23% of the growth in global oil consumption this year. But with the devaluation, oil stakeholders are wondering if China will continue to stockpile oil or pull back from the higher prices. Worries like these sent WTI crude oil down to $42 per barrel, the lowest since 2009.

China also accounts for about 45% of global copper demand. Unsurprisingly, copper fell to a six-year low ($2.27 per pound) after China’s announcement.

China is also a big commodities producer and, because of the devaluation, their costs have just dropped.

That’s bad news for the big miners – BHP Billiton (LONDON:BLT), Rio Tinto (LONDON:RIO), Anglo American (LONDON:AAL), and Glencore (LONDON:GLEN) – which sold off steeply.

Concern that China’s resources demand will weaken has also affected other commodities’ currencies, like the Australian dollar.

That fact lowers the costs of production (which is priced in U.S. dollars) for commodity producers in those affected countries, meaning weak players will stay in business longer than expected. This, in turn, will add to the glut in commodities, particularly in the metals and energy space, and keep prices low.

Barring a full-fledged currency war involving China, the long-term view holds a bottom and good buying opportunity in these commodities and the commodity producers.

Unfortunately, we’re not there yet.

Good investing,

by Tim Maverick