It’s the broken-record phrase of the financial industry...

“With higher risk comes higher reward.”

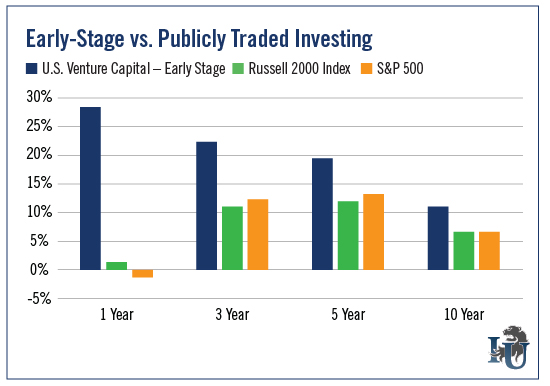

But there is a reason for this common quote’s existence. It’s a simple law of nature. And this week’s chart shows you that this isn’t just scientific theory.

Early-stage investing involves getting an equity stake in a company before it goes public. The earlier you invest in the startup process, the higher the risk and potential reward.

And the biggest rewards come when a private company you own a stake in goes public. This is when 10-bagger returns become a reality.

It’s All for the Cash, Man

An IPO is basically a fundraising event for private companies.

There are many reasons to take a company public. The credibility of being publicly traded can help build your brand. It also turbo-boosts share liquidity.

But the biggest reason is to raise cash.

The typical IPO raises between $100 million and $1 billion for a company. It’s the biggest payday for investors who got in before the event.

What may surprise you is that IPOs are not a 20th-century contrivance. They have been around for centuries.

The first modern IPO occurred in March 1602 when the Dutch East India Company offered shares to the public in order to raise capital. In the United States, the first IPO was for the Bank of North America around 1783.

Now, fast-forward 200-some years. In October, First Data Corporation (N:FDC) raised $2.5 billion in gross proceeds, making it 2015’s largest IPO.

Best Chance for a 10-Bagger

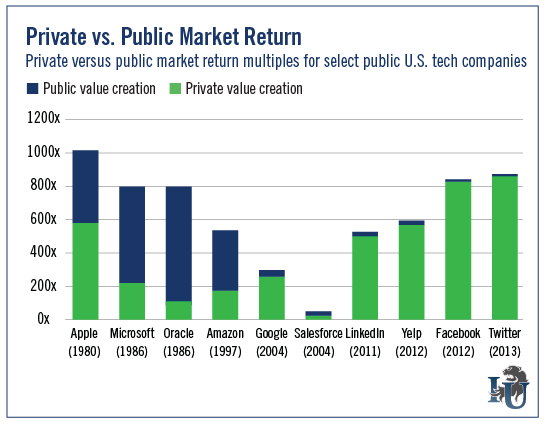

It’s the kind of gain every investor dreams about. Just imagine owning Microsoft (O:MSFT) early in the game.

When the company went public in 1986, it was valued at around $500 million. Over the next 10 years, the stock would rise more than 6,000%.

But the chances of this type of post-IPO return have dwindled.

Take Google (O:GOOGL) - now Alphabet (O:GOOG) - which went public in 2004. It had a valuation of $24 billion. Over the next 10 years, its stock would rise around 950%. A great return, but nowhere near the returns from Microsoft.

So what changed?

Small companies (especially fast-growing ones) are now waiting as long as possible to go public.

Over the last 40 years, we’ve seen an average of 250 IPOs per year. Since 2009, however, that number has dropped to 170 annually.

This overall trend has moved us toward larger and less frequent IPOs. And, as a byproduct, it’s made it so the greatest returns are available to only private institutions and wealthy, connected individuals.

Luckily, things are starting to change.

Lawmakers realized there was a problem. Small businesses were not getting the capital needed to grow and thrive. Plus, regular investors were being left out of huge investment opportunities.

So the JOBS Act was passed in 2012. This new set of rules allows everyone, not just rich “accredited” investors, to invest in private, early-stage companies.