I recently discussed why “Free, Isn’t Really Free” regarding the retail investor. While “free trades” have certainly reduced the transaction costs, the selling of data to the highest bidder has likely cost investors more than they saved. To wit:

“As is clear from the billions paid for order flow and the billions made from executing those orders, there is no such thing as ‘free trading.’ Thus, the claim of ‘commission free trading’ is often no more than a rhetorical ruse to attract new investors and distract from the billions of dollars in PFOF and other hidden costs that ultimately come out of retail investors’ pockets. It’s pretty clear that these intermediaries are often merely transferring the investors’ visible upfront commissions into invisible after-the-fact de facto commissions.”

However, there is another problem with “free trading” that will likely reduce your investing outcomes over time.

It’s A You Problem

Over the years, I’ve heard from several clients who have had trouble disciplining themselves from trading too frequently. That was in a low-cost world.

Now that trades are no-cost, it’s going to get a lot worse.

It’s difficult enough to match, much less beat, stock indexes without the drag of frequent trading. Frequent traders, from my experience, rarely do well in the stock market.

A Kiplinger article noted the same.

“In one study, Odean found that trading costs did indeed weigh on the performance of investors who traded more frequently. Such is a problem that no-commission accounts will render obsolete.

But no-commission trades won’t do anything about the results garnered from another study. Odean found that, ‘on average, the stocks these investors bought went on to underperform the stocks they sold.’

Speculative trading (trades that didn’t seem driven by, say, tax purposes or rebalancing concerns) was even worse. Across all trades, stocks that investors bought underperformed those they sold by three percentage points. However, that disparity widened to five percentage points when considering only speculative trades.

The zero-commission trade is bound to amplify the low-cost proposition of exchange-traded funds. By accelerating the huge migration of investor dollars away from actively managed mutual funds. Now, if investors simply stuck to buying broad-based index ETFs and holding them, that actually would be a good thing.

But what’s far more likely is that a big swath of these investors will trade more. They will try to pick ETFs and stocks that will beat the market over short time periods.After all, the trade is free – why not make it?”

Psychological Drag

So free trading may save you money on trading costs, but if it causes you to trade rashly, your returns may suffer. For most investors, investment returns are a much bigger deal than trading costs. Therefore, being able to trade for free can be counter-productive if it tempts you to become a day trader and tank your investment performance.

Such was the conclusion of Daniel Wiener, editor of The Independent Adviser.

“Free trading doesn’t help investors. It only encourages bad behavior. As someone who’s been managing client assets for more than 25 years, we talk about ‘time in the market, not market timing’ because long-term investing works.”

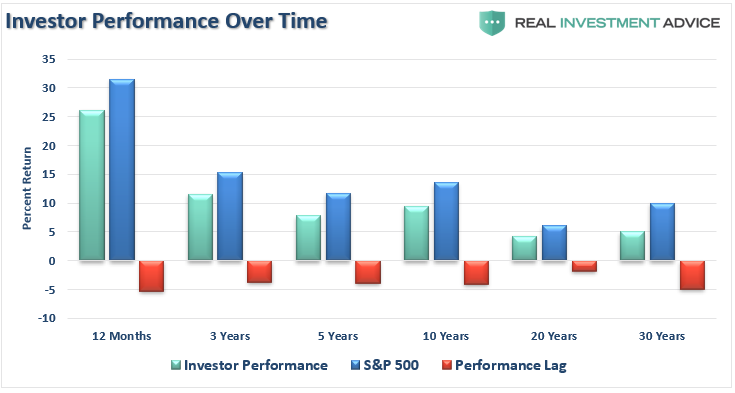

The annual Dalbar Investor Survey shows the same. Equity investors consistently do worse than the index.

Such is due primarily to the psychological pitfalls that occur from “herding” to “confirmation bias.”

“When discussing investor behavior it is helpful to first understand the specific thoughts and actions that lead to poor decision-making. Investor behavior is not simply buying and selling at the wrong time, it is the psychological traps, triggers and misconceptions that cause investors to act irrationally. That irrationality leads to buying and selling at the wrong time, which leads to underperformance.” – Dalbar

Another study by Barber, Lee, Liu, and Odean shows much the same:

“On average, individual investors lose money from trading. Barber and Odean (2000) document that the majority of losses incurred can be traced to trading costs. However, trading costs are not the whole story. On average, individual investors have perverse security selection abilities. They buy stocks that earn subpar returns and sell stocks that earn strong returns (Odean (1999)). In aggregate, the losses of individuals are material” – Barber, Lee, Liu, and Odean

Shrinking Holding Periods

Repeated studies show that long-term holding periods lead to better outcomes. Short-term trading, driven by overconfidence, generally leads to worse.

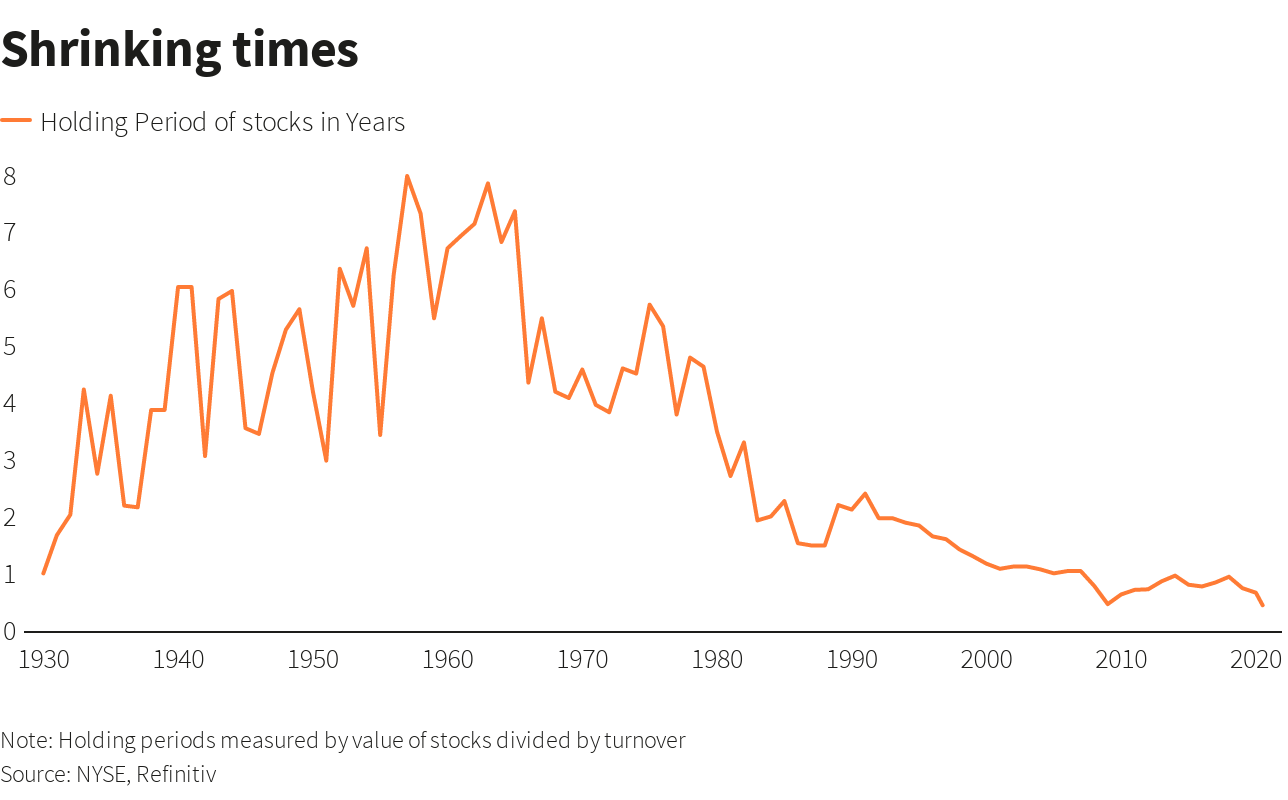

“The length of time that investors hold shares has been shrinking for decades but the trend accelerated this year. There are different ways of slicing it. However, Reuters calculations of NYSE exchange data show the average holding period for U.S. shares was 5-1/2 months in June. This was a decline from 8-1/2 months at end-2019.

The previous record low of six months was hit just after the 2008 crisis. In 1999, for example, 14 months was the average.” – Reuters

Why are holdings times shrinking?

“From 0% interest rates, pandemic-induced volatility to sports gamblers that are bored to death at home due to lack of sports betting. Then there are the millennials living in their parents’ basements with nothing else to do. Also, the day-traders by the millions playing the market using the Robinhood app. And the unemployed trying to multiply their $600+ weekly unemployment checks and also have fun doing it. Don’t forget those same people also throwing the $1,200 stimulus checks into the market to make some money to pay bills, etc. Not to mention algorithm-based machine trading by big institutions, locked-down realtors unable to flip houses finding their luck in the stock market, etc.” – David Hunkar via TFS

While the reasons for the continuing decline in holding periods are many, commission-free trading is exacerbating that trend by removing the “brake pedal” from the speeding car.

Whatever the cause, ultimately, investors’ inability to hold stocks for the long-term is damaging for the market and investors. Simply churning stocks all day long or even holding them for only a few months will not lead to a growing and robust equity market.

Right Solution For The Wrong Reason

One of the proposals by Democratic candidates, and hinted at by the current Biden Administration, is a “Financial Transaction Tax (FTT).”

An FTT is a proposal to place a “tax” on buying and selling a stock, bond, or other financial contracts like options and derivatives. Taxing stock trading is not new. America already has an FTT, albeit extremely small: currently set at roughly 2 cents per $1,000 traded.

According to the Brookings Institute, there are many problems with an FTT, harming savers and investors, reducing economic growth, and failing to raise the promised revenue by driving activities to lower-taxed areas overseas.

An FTT is a wrong proposal to solve the Government’s persistent overspending problem. However, it could reapply a “brake pedal” to slow over-trading by individuals. It also could discourage hedge funds from more predatory practices. Such could improve holding periods and longer-term returns.

The Wall Street Journal reported that online brokerages see record spikes in new accounts and trading activity in recent months. The authors argue this trend is due in part to the industrywide move to zero-commission trading. Platforms like E*Trade and Robinhood exacerbate this trend by providing individual investors to trade with few restrictions.

“Many are young and first-time traders confronting the first economic downturn of their professional lives. Yet with free trading at their fingertips and massive online communities with which to discuss trading ideas, many figure they have little to lose.

Research shows that individual investors tend to underperform the broader market, in part because of frequent trading. That hasn’t stopped scores of traders from taking the plunge.” – WSJ

Slowing It Down

As discussed previously, the selling of customer data provides high-frequency trading firms the ability to front-run retail investors.

“If people can find trading patterns and use that to make money, then fair play to them, but they should not be able to do that by selling information that does not belong to them. If they do not sell the information to anyone else, that reduces the scope for front running.” – Financial Times

The removal of payment for order flow, and a return to a transaction fee, remains the most sensible option. But, an FTT could accomplish the same.

“Proponents and opponents alike agree that an FTT would reduce high-frequency trading, or HFT. The profit margins on these individual trades are typically small—for example, profit margins could be as little as a few cents in a heavily traded stock. An FTT would make these trades unprofitable and drastically reduce, or even eliminate, HFT activity.” – Tax Foundation

While an FTT may indeed impact retail investors, resulting in reduced trading volume, it may also help squash the predatory effects of hedge funds and HFT’s.

“Some HFT-oriented trading firms have allegedly engaged in heavily scrutinized (and in some cases illegal) practices, publicized in Michael Lewis’ 2014 book Flash Boys: A Wall Street Revolt. These practices include frontrunning (detecting a large buy/sell order and moving in front of it in anticipation of the resulting price movement) and slow-market arbitrage (simultaneously buying and selling securities on separate exchanges to exploit small, transient price discrepancies).”

The removal of payment for order flow, and a return to a transaction fee, remains the most sensible option. But even an FTT might be worth considering if it reduces professional firms’ ability to take advantage of retail traders.

Free And Fair

As a fiscal conservative, I’m not too fond of taxes of any sort. I am a firm believer in “free markets.” However, for “free markets” to work effectively, they must also be “fair markets.”

Our current capital market system may be “free,” but it is not “fair” in many ways. Regulators should take steps to ban payment for order-flow, restrict high-frequency trading, and create markets that protect retail investors from predatory practices.

Such would mean that firms providing transaction services would have to go back to charging a commission for their services. But such would potentially have the knock-off effect of “slowing things down” and providing better investors’ outcomes.

However, the reality is that since Wall Street owns regulators, those money-making schemes already in place are likely to remain.

Therefore, while not a proponent, I can make the case an FTT would raise financial transaction costs, resulting in fewer of them. How this affects the overall economy depends on whether the reduced trading is beneficial. If it is, will the reduction will be significant enough to have an impact that goes beyond the investors and traders involved.

While the emergence of zero-commission trading is generally a win for investors, there’s one potential downside—the temptation to over-trade. In other words, it could be more tempting to move in and out of stock positions more frequently because it doesn’t cost anything to do it.

Don’t make this mistake. Although there are certainly some good reasons to sell stocks, the lack of trading commissions isn’t one of them.

But what we do need are “free” and “fair” capital markets.