They say that the four most dangerous words in investing/finance/economics are “This time it’s different.”

And so why worry, the thinking goes, about massive quantitative easing and profound fiscal stimulus? “After all, we did it during the Global Financial Crisis and it didn’t stoke inflation. Why would you think that it is different this time? You shouldn’t: it didn’t cause inflation last time, and it won’t this time. This time is not different.”

That line of thinking, at some level, is right. This time is not different. There is not, indeed, any reason to think we will not get the same effects from massive stimulus and monetary accommodation that we have gotten every other time similar things have happened in history. Well, almost every time. You see, it isn’t this time that is different. It is last time that was different.

In 2008-10, many observers thought that the Fed’s unlimited QE would surely stoke massive inflation. The explosion in the monetary base was taken by many (including many in the tinfoil hat brigade) as a reason that we would shortly become Zimbabwe. I wasn’t one of those, because there were some really unique circumstances about that crisis.[1]

The Global Financial Crisis (GFC hereafter) was, as the name suggests, a financial crisis. The crisis began, ended, and ran through the banks and shadow banking system which was overlevered and undercapitalized. The housing crisis, and the garden-variety recession it may have brought in normal times, was the precipitating factor…but the fall of Bear Stearns and Lehman, IndyMac, and WaMu, and the near-misses by AIG, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, Merrill, Goldman, Morgan Stanley, RBS (and I am missing many) were all tied to high leverage, low capital, and a fragile financial infrastructure. All of which has been exhaustively examined elsewhere and I won’t re-hash the events. But the reaction of Congress, the Administration, and especially the Federal Reserve were targeted largely to shoring up the banks and fixing the plumbing.

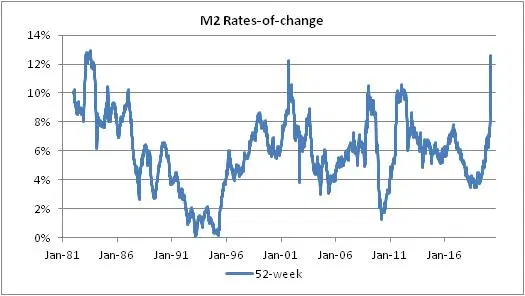

So the Federal Reserve took an unusual step early on and started paying Interest on Excess Reserves (IOER; it now is called simply Interest on Reserves or IOR in lots of places but I can’t break the IOER habit) as they undertook QE. That always seemed like an incredibly weird step to me if the purpose of QE was to get money into the economy: the Fed was paying banks to not lend, essentially. Notionally, what they were doing was shipping big boxes of money to banks and saying “we will pay you to not open these boxes.” Banks at the time were not only liquidity-constrained, they were capital-constrained, and so it made much more sense for them to take the riskless return from IOER rather than lending on the back of those reserves for modest incremental interest but a lot more risk. And so, M2 money supply never grew much faster than 10% y/y despite a massive increase in the Fed’s balance sheet. A 10% rate of money growth would have produced inflation, except for the precipitous fall in money velocity. As I’ve written a bunch of times (e.g. here, but if you just search for “velocity” or “real cash balances” on my blog you’ll get a wide sample), velocity is driven in the medium-term by interest rates, not by some ephemeral fear against which people hold precautionary money balances – which is why velocity plunged with interest rates during the GFC and remained low well after the GFC was over. The purpose of the QE in the Global Financial Crisis, that is, was banking-system focused rather than economy-focused. In effect, it forcibly de-levered the banks.

That was different. We hadn’t seen a general banking run in this country since the Great Depression, and while there weren’t generally lines of people waiting to take money out of their savings accounts, thanks to the promise of the FDIC, there were lines of companies looking to move deposits to safer banks or to hold Treasury Bills instead (T-bills traded to negative interest rates as a result). We had seen many recessions, some of them severe; we had seen market crashes and near-market crashes and failures of brokerage houses[2]; we even had the Savings and Loan crisis in the 1980s (and indeed, the post-mortem of that episode may have informed the Fed’s reaction to the GFC). But we never, at least since the Great Depression, had the world’s biggest banks teetering on total collapse.

I would argue then that last time was different. Of course every crisis is different in some way, and the massive GDP holiday being taken around the world right now is of course unprecedented in its rapidity if not its severity. It will likely be much more severe than the GFC but much shorter—kind of like a kick in the groin that makes you bend over but goes away in a few minutes.

But there is no banking crisis evident. Consequently the Fed’s massive balance sheet expansion, coupled with a relaxing of capital rules (e.g. see here, here and here), has immediately produced a huge spike in transactional money growth. M2 has grown at a 64% annualized rate over the last month, 25% annualized over the last 13 weeks, and 12.6% annualized over the last 52 weeks. As the chart shows, y/y money growth rates are already higher than they ever got during the GFC, larger than they got in the exceptional (but very short-term) liquidity provision after 9/11, and near the sorts of numbers we had in the early 1980s. And they’re just getting started.

Moreover, interest rates at the beginning of the GFC were higher ( 5-Y rates around 3%, depending when you look) and so there was plenty of room for rates, and hence money velocity, to decline. Right now we are already at all-time lows for M2 velocity and it is hard to imagine interest rates and velocity falling appreciably further (in the short-term there may be precautionary cash hoarding but this won’t last as long as the M2 will). And instead of incentivizing banks to cling to their reserves, the Fed is actively using moral suasion to push banks to make loans (e.g. see here and here), and the federal government is putting money directly in the hands of consumers and small businesses. Here’s the thing: the banking system is working as intended. That’s the part that’s not at all different this time. It’s what was different last time.

As I said, there are lots of things that are unique about this crisis. But the fundamental plumbing is working, and that’s why I think that the provision of extraordinary liquidity and massive fiscal spending (essentially, the back-door Modern Monetary Theory that we all laughed about when it was mooted in the last couple of years, because it was absurd) seems to be causing the sorts of effects, and likely will cause the sort of effect on medium-term inflation, that will not be different this time.

[1] I thought that the real test would be when interest rates normalized after the crisis…which they never did. You can read about that thesis in my book, “What’s Wrong with Money,” whose predictions are now mostly moot.

[2] I especially liked “The Go-Go Years” by John Brooks, about the hard end to the 1960s. There’s a wonderful recounting in that book about how Ross Perot stepped in to save a cascading failure among stock brokerage houses.