Investing.com’s stocks of the week

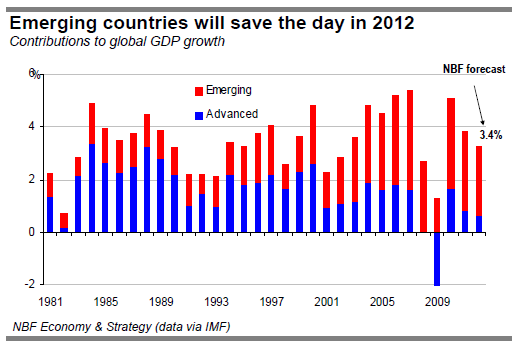

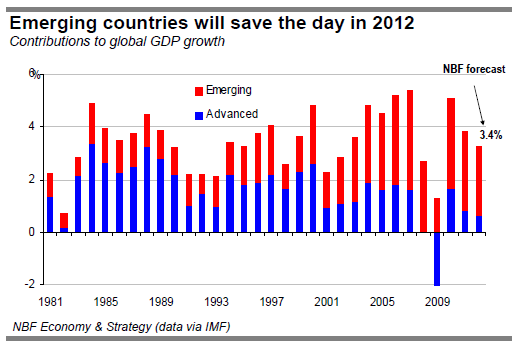

It’s been a difficult year for the global economy. We see continuing deceleration in 2012. The crisis of public finances in the euro zone has undercut the economy of the region: the fiscal austerity forced on virtually all of its governments has made a recession practically inevitable. Despite an anticipated rebound in the U.S., the advanced economies as a group are likely to grow less in 2012 than in any of the last 30 years outside the recent recession. The emerging economies, however, with their ever-growing weight in the world, can be expected to pull global growth to 3.4% in 2012.

The cyclical rebound from the economic and financial crisis of 2008-09 turned out to be short-lived. We estimate 2011 global economic growth at 3.9%, the lowest since 2003, excluding the last recession. A number of headwinds arose in the first half of the year. Strong inflationary pressures, notably in energy and food, crimped consumer purchasing power around the world. In many countries, mainly those whose labour markets have been slow to recover, income gains have barely matched inflation. Consumer spending has slowed accordingly. Then Japan was struck by a tsunami that destroyed much of its industrial plant and disabled global supply chains for months. Though these factors are unlikely to affect growth in 2012, euro-zone public finances will remain the focus of investor attention.

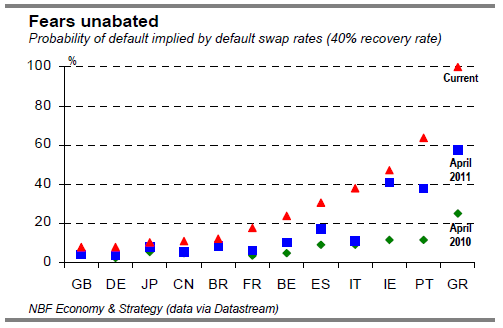

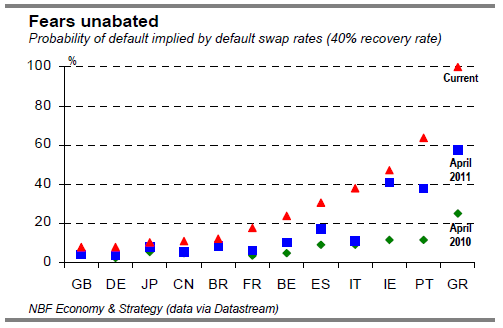

In Europe, the crisis that began in the spring of 2010 with worries about the solvency of Greece has ended up spreading throughout the zone. European leaders have been unable to agree on action that would limit investor apprehensions to the worst-off of the euro countries. The default swap market registers fears about Italy greater than those about Greece in April 2010. The soaring cost of Italy’s borrowing is made especially perilous by the country’s high debt load. The upshot is that stabilizing its debt-to-GDP ratio will take measures much more drastic than initially foreseen.

In our view, the size of Italy’s debt and its importance in the European banking system require that the authorities keep its financing costs sustainable, especially since Italy, unlike Greece and Portugal, is generally regarded as solvent. Things would probably not have reached this pass had European leaders not done too little, too late as investor apprehension mounted. Economists have long insisted that monetary union is not viable without fiscal union. There has been real progress recently, not least in a plan to improve the Stability and Growth Pact that would entail a loss of fiscal sovereignty for member countries whose deficits or debt exceed set limits. To survive, however, we think the euro zone must ultimately go further, harmonizing its economic and social policies on a model more favourable to growth and more sustainable in the long term. In the meantime, further short-term measures will also be necessary to limit the financing costs of Spain and Italy. Since insufficient funds are available to bail out these countries, it seems increasingly clear that the rescue of the euro zone will require issuance of eurobonds, ECB purchases of new bond issues, or both.

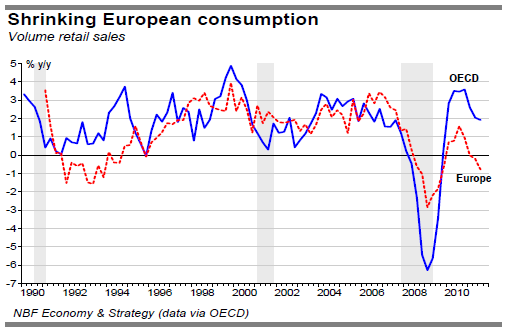

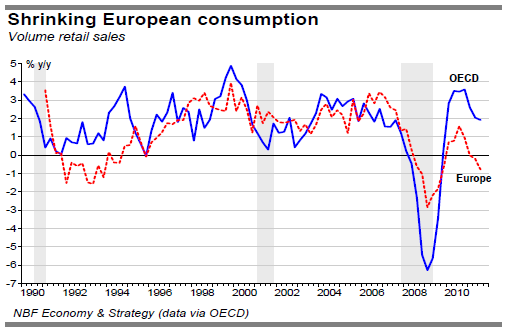

For the euro economies, the damage has been done. Most countries of the zone are being forced to eliminate their deficits much faster than they had planned. The resulting across-the-board fiscal austerity is likely to plunge the zone into its second recession in less than four years, especially since the climate of uncertainty has undermined household and business confidence. Industrial production has been in decline for two months now and retail sales are down from a year ago. These conditions could exacerbate pressures on governments and financial institutions as they wrestle with their heavy indebtedness. In our view, however, the central banks have the tools in place to move quickly to prevent the economic downturn from becoming a financial crisis.

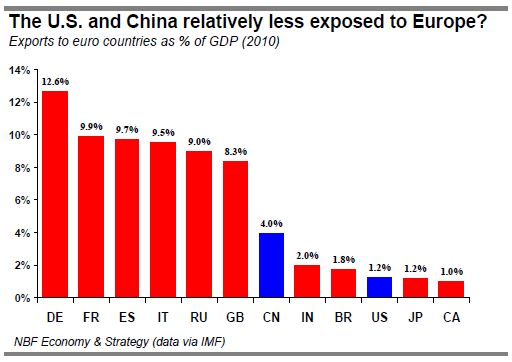

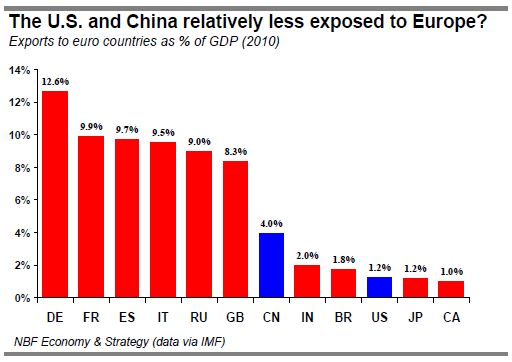

Even Germany, whose austerity measures need not be as sweeping as those of other euro countries, is unlikely to come through unscathed. Germany exports a hefty 12.6% of its GDP to other euro countries. The euro zone’s neighbours may also feel the shock waves. The U.K., already facing an outlook of slow growth in its domestic economy, will grow hardly at all if its major trading partners stumble. The Chinese and U.S. economies, on the other hand, are much less exposed. Their exports to the euro zone amount to only 4.0% and 1.2% of GDP respectively. So if European governments and central banks can stop their recession from turning into a credit crunch, the two heavyweights of the global economy will pull through.

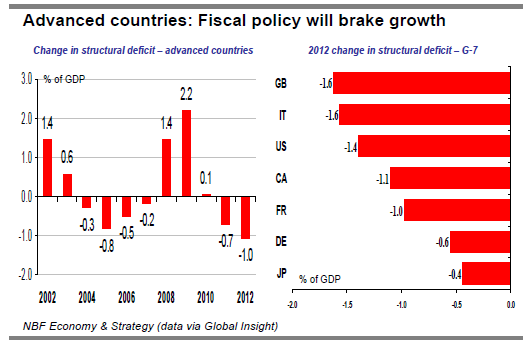

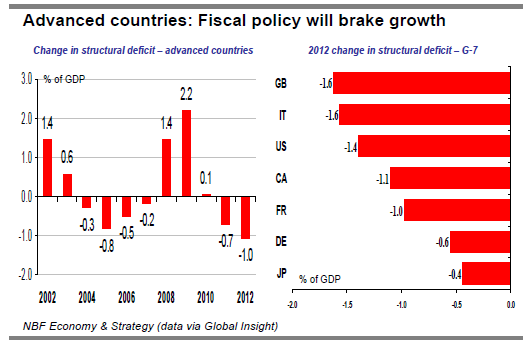

The scope of the austerity that will grip the advanced economies in 2012 can be seen in IMF projections of changes in structural deficits, illustrating the effect of discretionary changes to government budgets as of September. At that time the IMF considered that the braking effect of fiscal policy in the advanced countries would be the sharpest since it began compiling the data in 2002 – 40% sharper than in 2011. And it is quite possible that the fiscal braking will be even more severe than expected, since countries including France and Italy have adopted additional austerity measures since September.

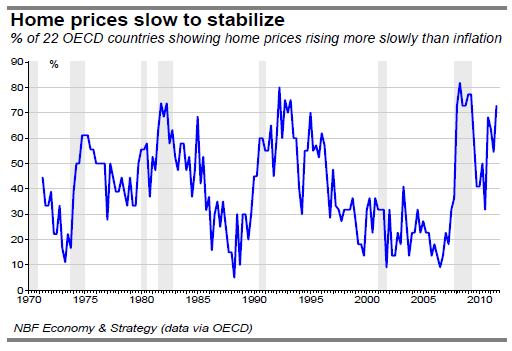

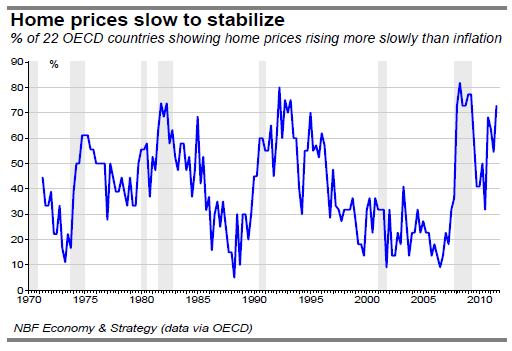

The watch list includes, besides governments, the real estate sectors of the advanced economies. The housing market is exposed to additional risk as a number of countries go into recession. We are especially surprised to see 16 of the 22 OECD countries for which data are available reporting deflation of real home prices in the most recent quarter for which data are available. One reason is that the demographics of European countries including Germany, Spain and Italy are unfavourable

to real estate – the ranks of their first-time homebuyers are depleting sharply. This trend, combined with a euro-zone labour market that is especially hard on young people, suggests to us that the housing sector in some advanced countries may remain under pressure over the coming quarters.

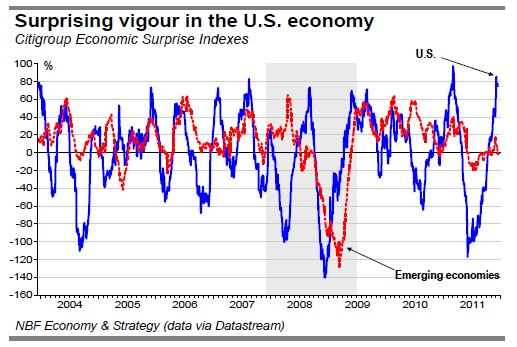

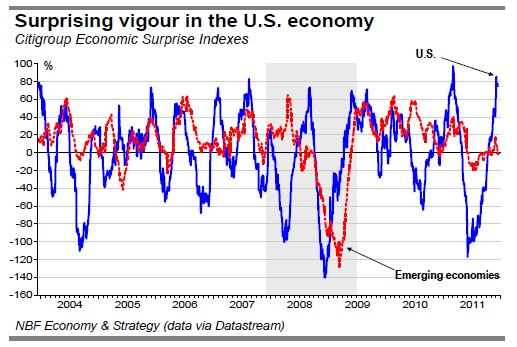

As the euro economy deteriorates, the U.S. economy has been gaining strength. The Citigroup Economic Surprise Index for the U.S. recently approached its most positive reading ever. We are especially comforted by improvements in the labour market at a time when an unusually divided political landscape has generated high uncertainty about fiscal policy. Despite these risks, we see the U.S. economy accelerating to growth of 2.5% in 2012 after a difficult 2011 (see U.S. section for details). As for the emerging economies, which bulk ever larger in the world economy, current indicators are essentially in line with the consensus expectation.

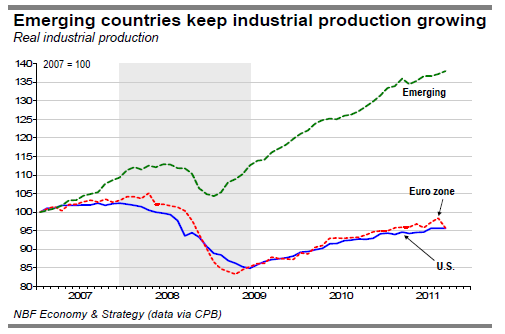

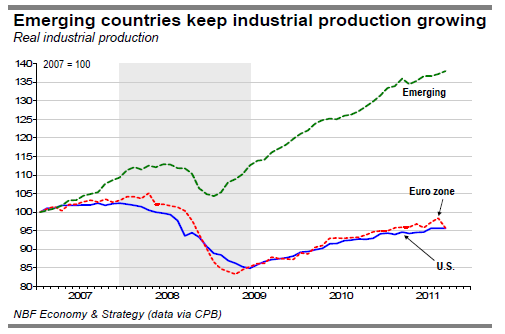

World industrial production, meanwhile, is still trending up, mainly as a result of a surge in the emerging economies. However, recession in Europe is likely to slow imports from Asia. A recent deceleration of China’s economy aroused apprehension, though the 9.1% growth rate of its third quarter would be the envy of almost any other country. It should be kept in mind that to counter inflation, Beijing has considerably reduced its monetary accommodation in an attempt to cool its economic growth rate to about 8%. However, the anticipated sluggishness of the advanced economies in 2012 is likely to slow China’s growth to a rate below that threshold.

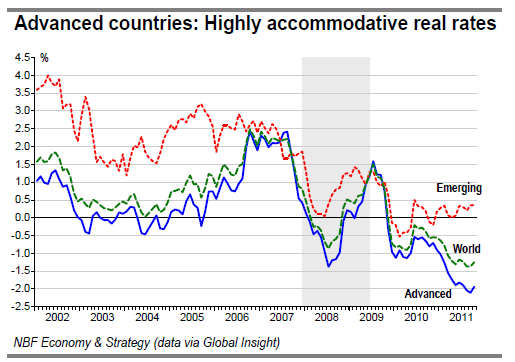

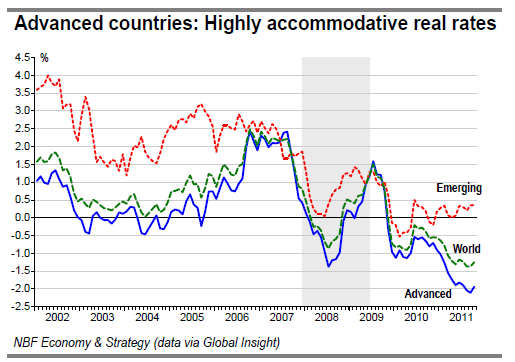

In that event, Beijing can be expected to offset export softness by stimulating domestic demand, especially since recent reports show a sharp deceleration of consumer prices. The recent decline of commodity prices, in response to a decline of physical and financial demand and to the rise of the U.S. dollar, will ultimately show up as disinflation. If the economic picture deteriorates further, inflation fears will completely dissipate and a number of central banks, especially in emerging countries, could put their shoulders to the wheel. In the advanced countries, real short rates are now more stimulative than in 2008. In addition, several central banks use unconventional monetary stimulus currently.

All these factors considered, we see the advanced economies taken together as likely to expand 1.3% in 2012. Outside the great recession of 2008-09, that would be the weakest annual growth of the last 30 years. Yet the emerging economies, given their growing share of world output, are likely to push global growth to 3.4% in 2012.

From 1980 to 2000, the advanced economies accounted for 63% of global growth. Since 2000 they have accounted for 28%. This new reality justifies optimism in the face of old-world difficulties.

It’s now clear that the U.S. economy not just avoided recession in 2011 but in fact accelerated as the year progressed. GDP in Q4 is tracking well above 2% annualized, the best quarterly performance of 2011. Momentum should carry through to 2012, with the US achieving above-potential growth for the first time in six years, helped by resilient domestic demand and inventory rebuilding. The big caveat, however, is that a European-triggered global financial crisis is averted by policymakers who would, presumably, have learnt about the devastating costs of inaction à la 2008.

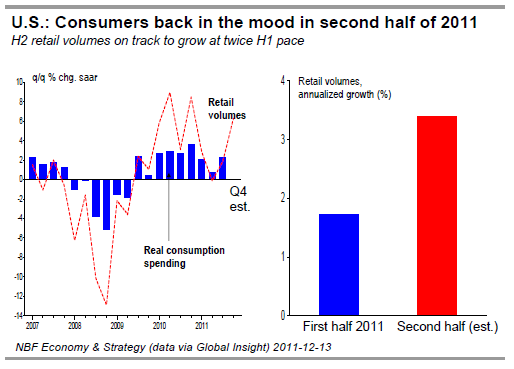

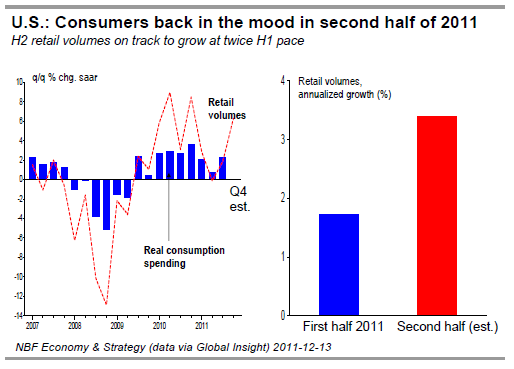

The U.S. economy has rarely done badly when its consumers have been in a spending mood. Its acceleration in the second half of 2011 was largely a result of consumers getting their mojo back. With two months in, Q4 real retail spending is tracking + 6.3% annualized, the highest since Q4 of 2010. Retail volumes in the second half of 2011 are on track to grow at twice the pace of the first half.

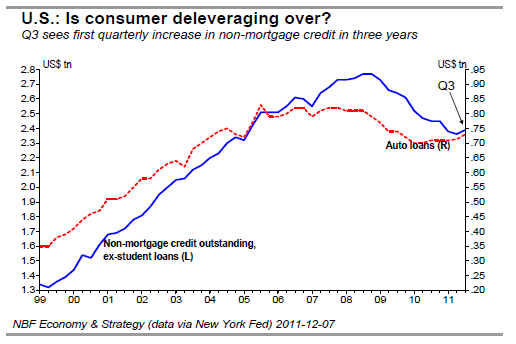

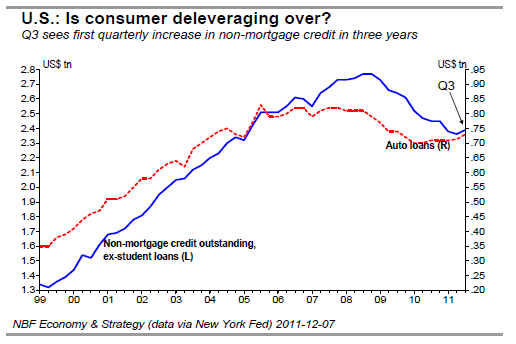

The outlook for 2012 consumer spending seems positive, partly because of a slower pace of deleveraging. Mortgage credit outstanding continues to drop, but more slowly than before. In Q3, moreover, non-mortgage credit (even excluding student loans), led by auto loans, showed the first quarterly increase in three years. Together with a stabilization of the savings rate, these are signs that the worst of the deleveraging process may be over.

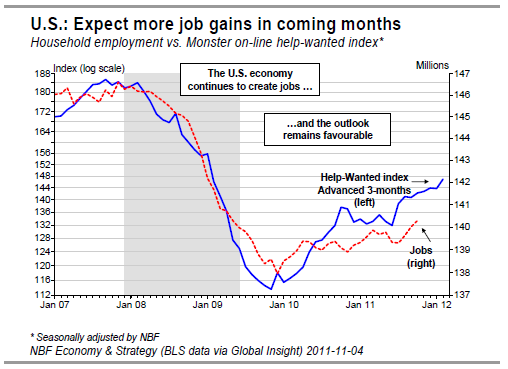

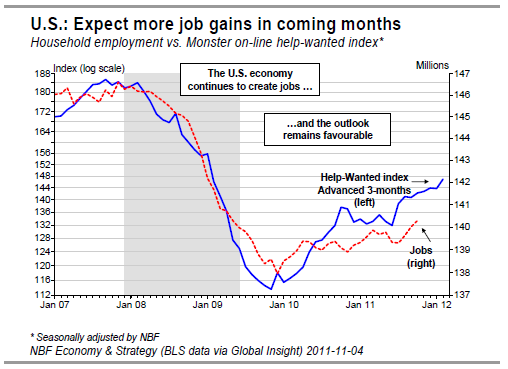

Another plus for consumer spending is the recovery now under way in employment. Non farm payrolls rose 681,000 from June through November, with all gains coming from the private sector. The household survey also shows a clear improvement in the labour market – full-time employment up 759,000 over the same period. In November more than 113 million Americans were employed full-time, the most since April 2009. Odds are that the uptrend will extend into the new year, particularly given the strength of helpwanted listings, which tend to lead the household employment survey.

Complementing the improvement in credit and the labour market in 2012 will be a diminished drag on consumer spending from the negative wealth effect of home prices.

Has housing finally hit bottom?

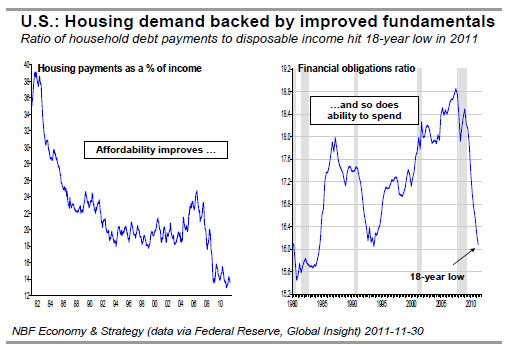

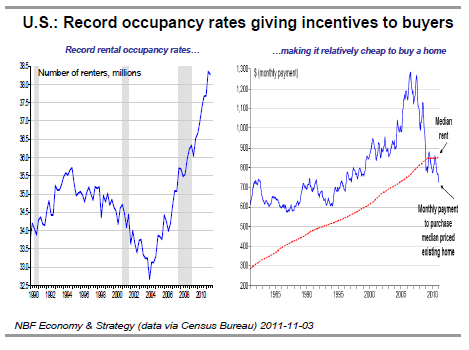

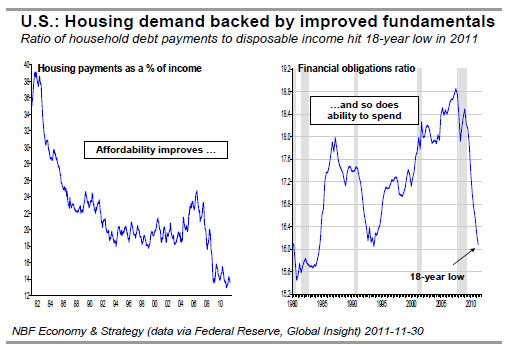

While it’s too early to say whether the double-dip housing recession is definitely over, there are signs suggesting some stabilization ahead. Residential investment grew in both Q2 and Q3, the first back-toback quarterly increases since 2005. The pace of home-price deflation seems to be moderating as supply and demand come into better balance. Thanks to lower mortgage rates and depressed home prices, affordability is the best in a generation. That, coupled with an 18-year low in the financial obligations ratio, makes borrowing more likely.

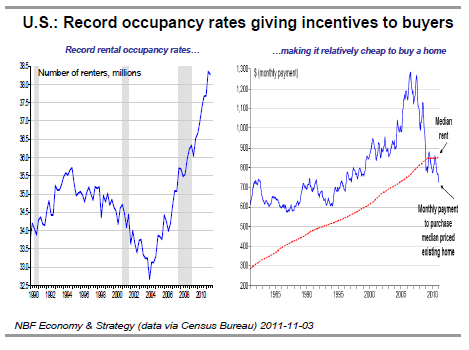

Moreover, higher rental demand has driven rents high enough as to give renters incentives to become home owners. On the supply side, while inventory remains large, the drop in foreclosure rates is also helping somewhat in keeping supply growth under control. The overall improving market conditions explain perhaps why builder confidence in December was the second highest since 2007, according to the National Association of Home Builders. That said, don’t expect a significant turnaround in the housing market just yet. A flattish trend is more likely for home prices in 2012, with improving demand likely to be offset by supply increases from both new construction and foreclosures that have yet to hit the market. But importantly, the reduced drag from housing should be supportive of consumption spending in 2012.

Business investment to remain solid

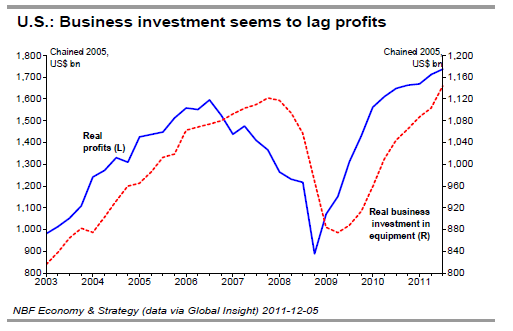

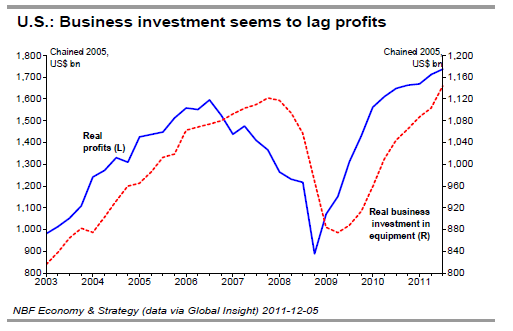

Domestic demand is likely to gain further support in 2012 from investment spending as businesses seek to maintain the growth of productivity and profits. Though U.S. output is now back to pre-recession levels, employment remains 5% or so below the prerecession peak. In short, the U.S. is doing more with less. This productivity boost has come from massive capital outlays over the last couple of years, with investment in equipment and machinery now back to pre-recession levels after growing 15% in 2010 and roughly 10% in 2011. Given the solid corporate profits of 2011 and the usual lag between profits and investment, there is reason to expect capital spending to continue at a healthy pace in 2012, particularly if global economic uncertainty dissipates somewhat.

economy was subjected to a near government shutdown in April, a debt-ceiling drama and the ensuing US credit downgrade by S&P in July/August, and the failure of the Super Committee in November. December saw further debates and footdragging by Congress on what ought to be a straightforward decision on the extension of payroll tax cuts. The fiscal outlook remains unclear. Assuming nothing else changes on Capitol Hill (and the current political impasse suggests just that outcome) the US economy will face $2.1 tn in spending cuts over ten years. Add to that the end of the Bush-era tax cuts and the potential fiscal drag rises to over 2% of GDP in 2013. Facing the prospect of a recession-inducing fiscal drag, a new Congress after the 2012 Presidential elections will very likely kick the can down the road.

The inventory cycle to boost 2012 GDP

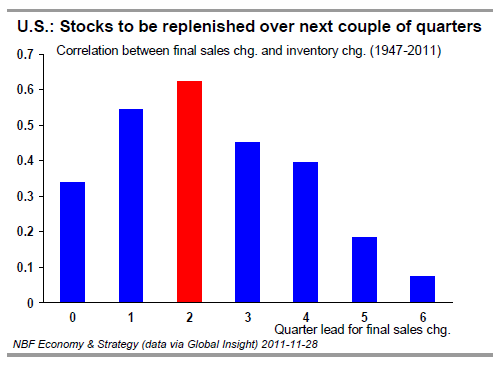

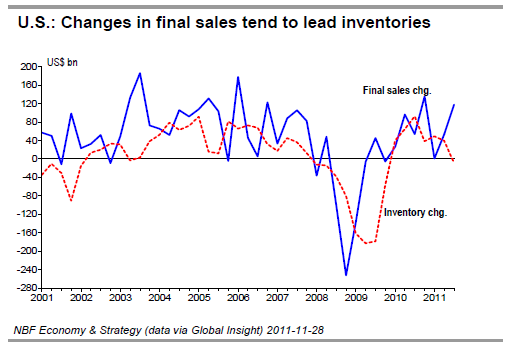

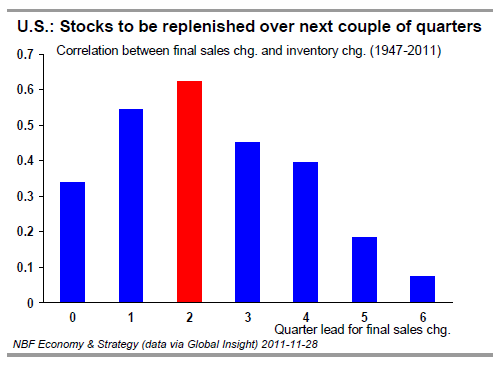

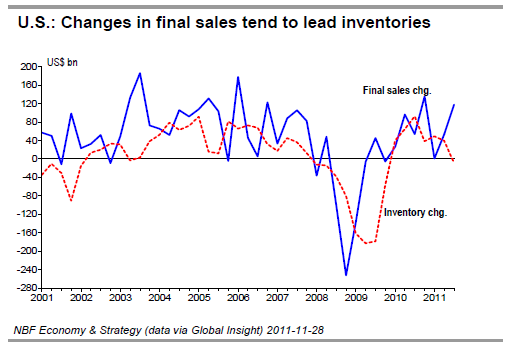

Having braked growth in 2011, inventories are set to contribute to it in 2012. Destocking has chopped 3.3% off GDP in the last four quarters alone (Q410 to Q311), the largest 4-quarter cumulative drag outside of a recession in 25 years. Now, unless we’re in a recession or heading precipitously towards one, such inventory cuts are unsustainable. In our view, with domestic demand seemingly still resilient, it’s a question of time before the restocking process kicks back into gear. History suggests there tends to be a couple of quarters lag in the inventory response to changes in final sales.

So, the surge in final sales in Q3 bodes well for inventory rebuilding over the next few quarters, assuming of course that the global economic picture doesn’t darken any further.

Trade supported by a competitive US dollar

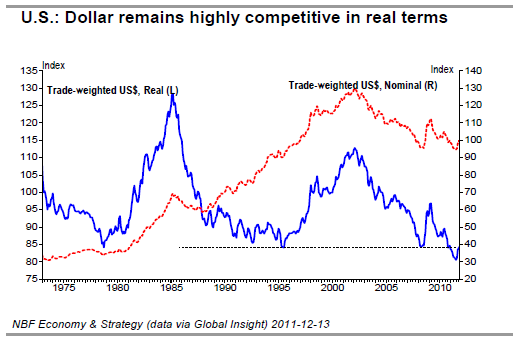

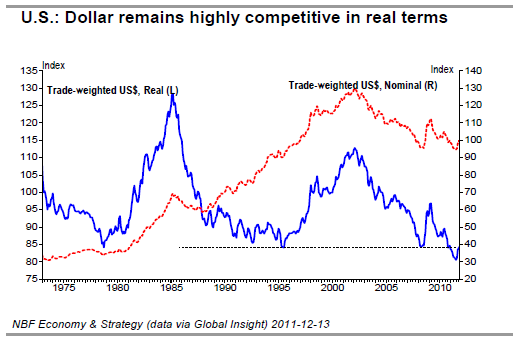

The resilience of domestic demand will be especially welcome in 2012 as global growth slows. Trade may face some headwinds as a European recession translates into sluggish demand for American exports. That said, the overall impact on US growth isn’t likely to be significant, particularly given that only 20% or so of US exports go to Europe, and exports account for less than 14% of the overall US economy. Moreover, the highly competitive U.S. dollar, which in real terms is still near historic lows, will provide some offset, especially in markets of buoyant demand such as Asia and South America.

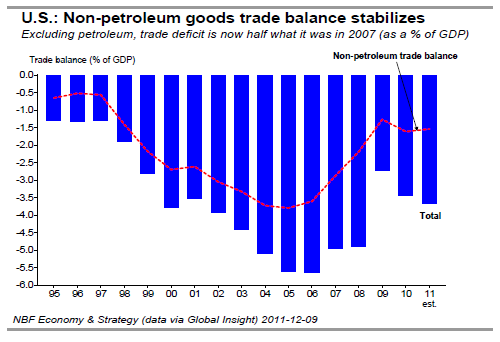

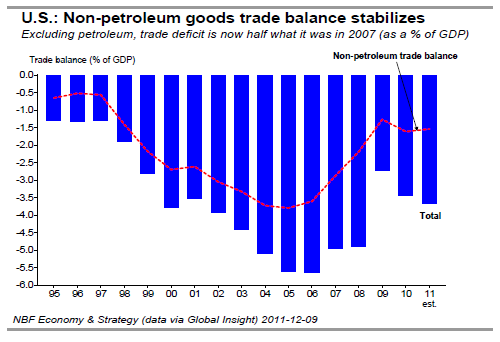

Further down the road, exports are set to benefit from the long-term trend of depreciation of the U.S. dollar. On trade fundamentals alone, the greenback needs not depreciate much more: the trade deficit excluding petroleum is stabilizing at just 1.5% of GDP. Depreciation pressures will come from elsewhere – the country’s precarious fiscal position, the Fed’s easy money policy, China’s reduction of its foreign exchange reserves. We see the USD losing ground against most currencies, primarily the yuan and the OPEC currencies if the latter are allowed to come off the peg.

crisis, perhaps via sovereign defaults. According to data from the Bank of International Settlements, US exposure to European banks stood at US$3.8 tn at the end of Q2. Taking into account derivative contracts, guarantees and credit commitments, the exposure rises to roughly US$5.9 tn. Although the bulk of that is being held by the nonbank private sector, the banking sector also has significant exposure (over US$700 bn). No wonder that CDS spreads for American financials have risen

in tandem with European ones as the debt crisis intensified on the old continent. Should European debt turn sour, expect US banks to take write-downs triggering balance sheet repairs via recapitalizations and asset sales. That eventuality – a credit crunch – is the major channel through which Europe could affect the United States.

QE3 in 2012?

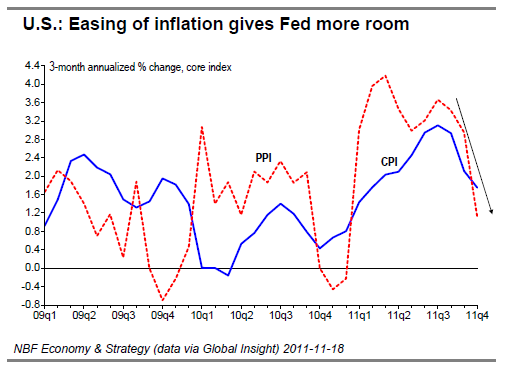

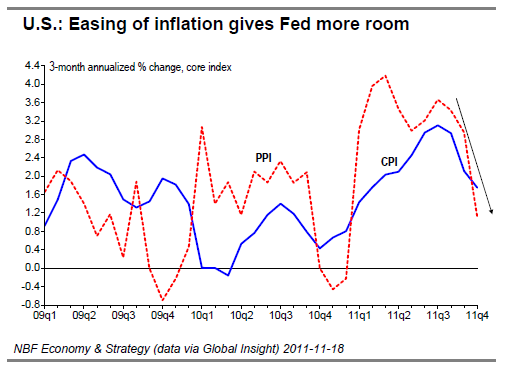

Fortunately, the US has a more proactive central bank than Europeans do. While an improving US economy and better credit flow make a third round of unsterilized bond purchases (QE3) less necessary at this point, a European-triggered credit crunch would have the Fed take prompt action. The recent easing in inflationary pressures, with both the CPI and PPI on a declining path, and stable inflationary expectations, give the Fed more room to act if necessary. Note that even with the currently wellfunctioning financial markets, FOMC members continue to talk about the possibility of unleashing QE3 as a way of stimulating the economy. Should credit markets freeze à la 2008, expect talk to translate into action.

All told, barring a European-triggered global financial crisis and subsequent world recession, US economic growth should accelerate to an above-potential 2.5% in 2012 thanks to a combination of resilient domestic demand and inventory rebuilding. Fiscal drag will continue to impose a speed limit on the economy in 2012, although that will pale in comparison to the impacts seen in 2013 and beyond.

Facing challenges both at home and abroad in 2012, Canada stands to underperform the US for the first time in six years. Domestic demand will be under siege from a likely softening in housing, and a more moderate pace to consumption spending. Trade will be vulnerable to the lagged impacts of a strong Canadian dollar although there will be some offset in the form of increasing demand from an accelerating US economy. With domestic demand treading water and European inertia threatening to trigger a global financial crisis, the Bank of Canada is likely to delay rate hikes to 2013.

Labour market deceleration in 2012

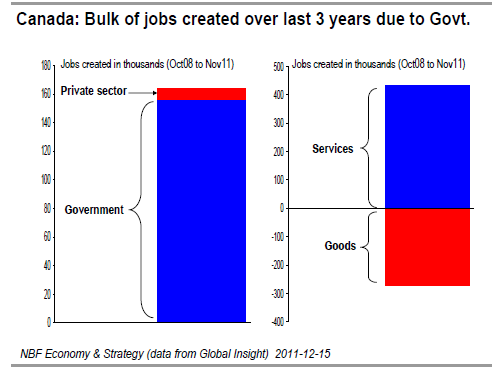

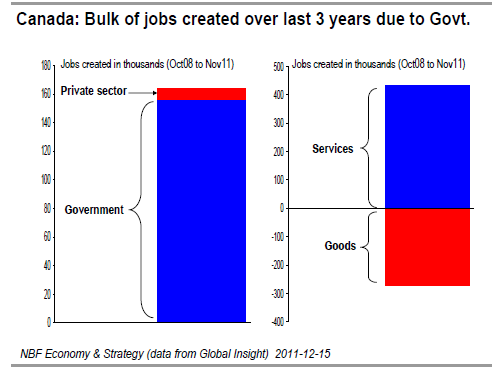

Canada’s labour market recovery has been much stronger than that of the US, with employment here now above the pre-recession peak compared to American payrolls still languishing 5% below prerecession levels. The difference between the two countries has, of course, been the relatively better economic growth in Canada. But government payrolls have also been a big driver in boosting Canadian employment. Over the last three years (Oct08 to Nov11), Canada has added roughly 164,000 jobs, 95% of which came from government. Contrast this with the US where the purge in public sector payrolls has been unprecedented. The increase in hiring by government together with the 278,000 job gains in private sector service-producing industries lifted total services employment enough as to offset the purge in the goods sector payrolls.

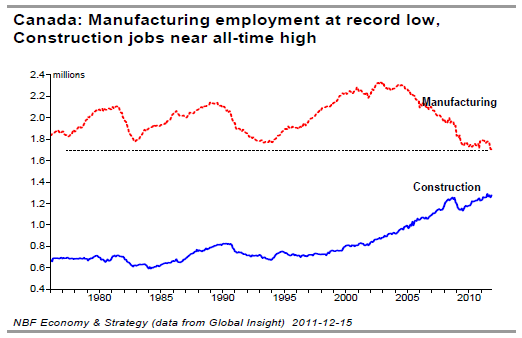

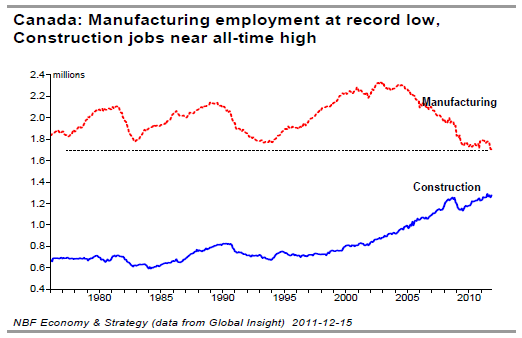

The employment slump in the goods sector was driven by the manufacturing sector whose payrolls are at a record low. This avalanche of pink slips from factories was partially offset by the uptrend in construction employment which reached new highs in 2011.

What do those patterns suggest for the 2012 employment? Simply put, those trends aren’t bullish. The destruction of manufacturing jobs is symptomatic of a structural problem that’s not going away anytime soon (C$ impacts are described further on). And the gains in construction jobs which have been fed by stimulus programs and the expansion of housing, are likely to reverse as both of those boosters fade in 2012. Hiring in the resources sector may provide some support, although the expected softening in commodity prices should limit employment gains there. In any case, any job gains in the resources sector, which accounts for less than 10% of overall goods sector employment, are unlikely to have a significant positive impact. So expect the goods sector payrolls to remain weak.

This time, however, there won’t be as much of an offset from services payrolls. Government hiring at the pace seen over the last three years isn’t sustainable, nor likely to be permitted to continue particularly with deficit-cutting plans underway. The saving grace for Canadian employment in 2012 may be from private sector service-providing sectors, but even there we’re not expecting miracles given the anticipated softening of the overall economy. All told, employment growth should be modest at just under 1% in 2012, contrasting with a roughly 1.5% increase in the prior year. That should leave the unemployment rate averaging north of 7% in 2012.

Consumers under stress

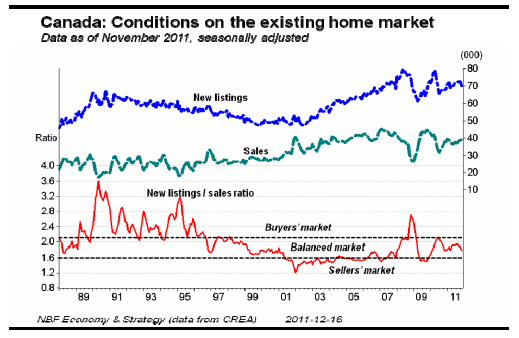

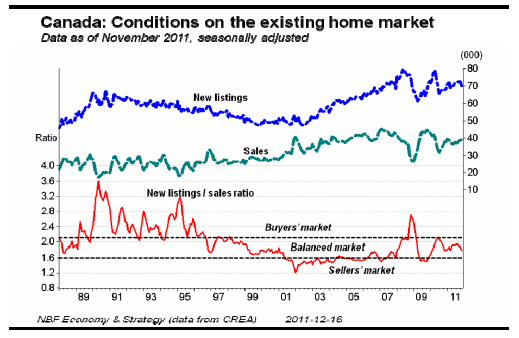

A tepid labour market will evidently weigh on consumption spending in 2012. However, a slower global economy should cap gasoline prices which will offer Canadians some relief. That’s pretty much the reverse of the scenario that played out in 2011 when the benefits of a relatively strong labour market on consumption spending was offset by high gasoline prices. Another difference will be the impact of the housing market on consumers. For now the Canadian housing market is being described as

“balanced” with the listings-to-sales ratio remaining low enough as to allow home prices to rise at a modest pace.

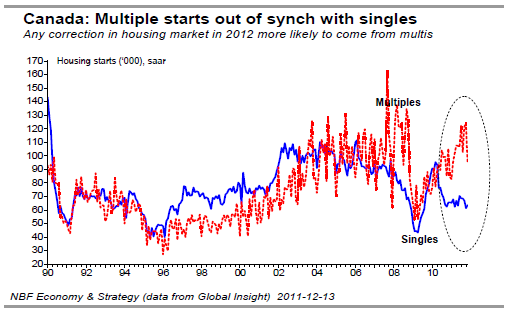

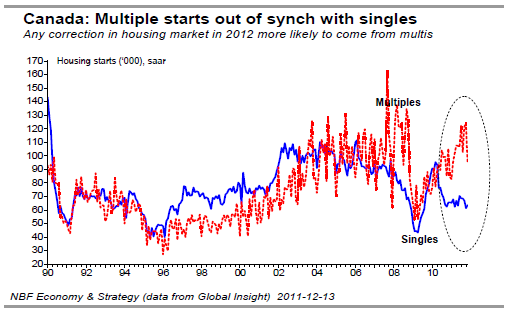

But with the labour market likely to decelerate, the resulting weakness in household incomes should work as to bring the existing home market closer to buyers’ market territory, hence limiting price increases or even prompting price declines in some cases. The market for multiple units e.g. condos, apartments, seem more prone for a price correction given how far new supply has strayed from that of singles.

So the housing wealth effect which has helped boost consumption spending over the last several years is likely to be less of a factor going forward.

How serious is the deleveraging threat to consumption spending?

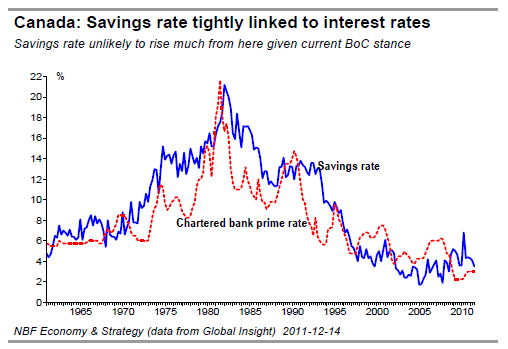

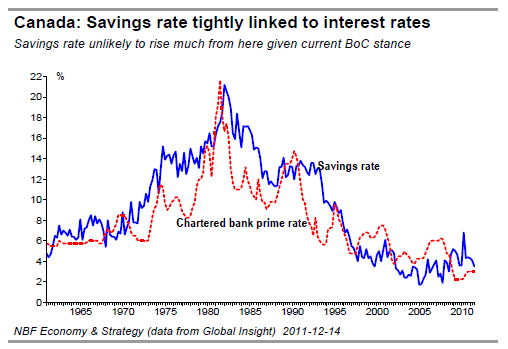

We are less concerned about the negative impacts of deleveraging on consumption because we do not expect the savings rate to rise significantly given that interest rates are set to remain low for a while. Rock bottom interest rates are clearly discouraging savings and encouraging debt accumulation.

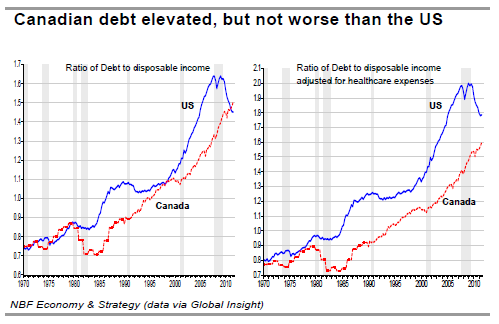

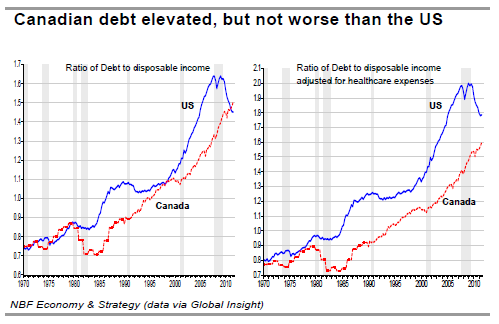

The Bank of Canada is in a bind because it’s being forced by global events to keep interest rates low, hence fueling the debt accumulation spree of Canadians. In fact, the longer the BoC delays rate increases, the harder it will be for it to raise rates without triggering a housing-led recession. Which is why the BoC felt that it had to, repeatedly, warn Canadians against over-leverage, going so far as to say that “Canadians are now more indebted than the Americans”. While the latter statement may be true if one looks at an unadjusted ratio of household debt to disposable income which is indeed higher in Canada, the comparison is arguably unfair. Disposable incomes of Americans aren’t exactly comparable to Canadian ones since the former get a lot less bang for the buck having to assume more significant expenses like health care outlays. An adjusted ratio, which removes health care expenses from the calculations, shows that Canadians aren’t quite as levered as Americans.

That said, there’s no denying that the Canadian debt picture isn’t pretty. Canadians will find it harder to service their debt once interest rates resume their ascendancy. But rates are set to remain low over the next several years, meaning that debt servicing costs should remain manageable over the near to medium term. Deleveraging would become a more serious problem for consumption spending if interest rates rise quickly or if the housing market collapses. We’re not expecting either of those to materialize. Still, consumers will face enough challenges as to limit spending growth to less than 2% in 2012.

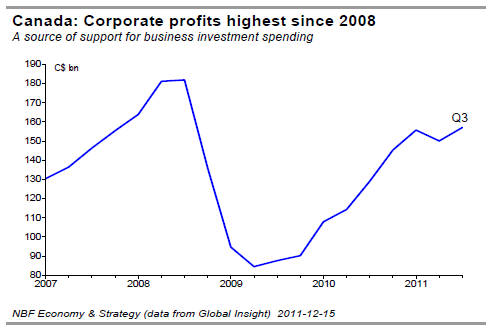

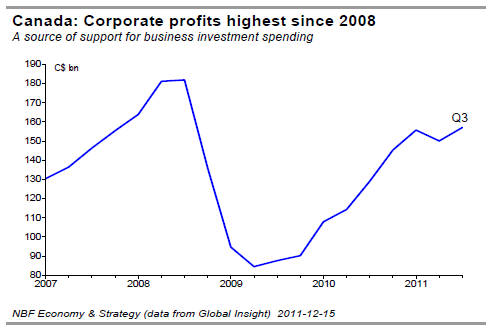

Providing a partial offset in 2012 to a flatlining housing market and the anemic growth in consumption and government spending, will be business investment spending. Buoyed by strong corporate profits, low interest rates and a strong Canadian dollar, business outlays have decent fundamentals for expansion. Planned outlays relating to projects in energy, namely hydro and the oil sands will also help support investment. That, however, won’t prevent overall domestic demand to ramp down to a sub-2% performance in 2012.

Canadian Trade: Currency impacts offset by accelerating US economy

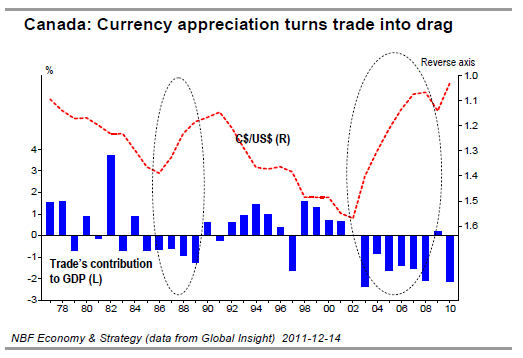

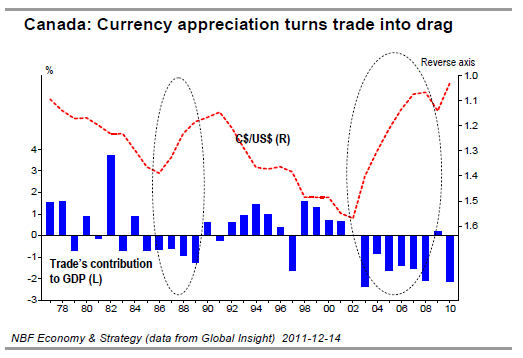

With the US economy going up one gear in 2012, demand for Canadian exports should improvesomewhat. However, it’s not going to be smooth sailing for our exporters. With only 5% or so of their products going to Europe, Canadian exporters are lucky to not have significant direct exposure to waning demand from the old continent. However, exporters of resources, will feel an indirect hit as the European recession weighs enough on global growth as to bring down commodity prices. Non-resource exporters may get some lift from an accelerating US economy but will be hampered by the lagged impacts of a strong Canadian dollar. Note that the merchandise trade balance remained in deficit territory for the third year in a row in 2011. And, as has been the case for seven of the eight preceding years, trade was likely again a drag on the economy in 2011. So the currency’s impacts can be significant.

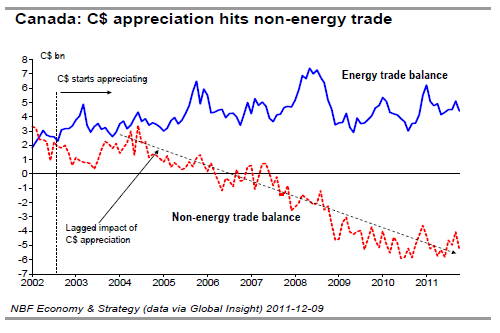

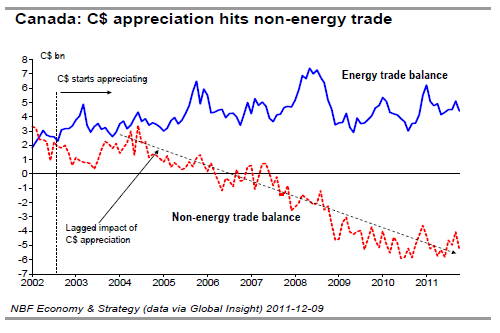

Commodity prices, which are largely determined on global markets, have been on the rise over the past several years courtesy of the growing clout of emerging markets in the world economy, fuelling the Canadian dollar’s ascent. While higher prices have allowed our resource exporters to cushion the blow of the stronger currency, non-resource exporters haven’t been so lucky. In fact, excluding resources, Canada’s trade performance has been largely disappointing, with the non-energy trade balance on a steady decline in recent years.

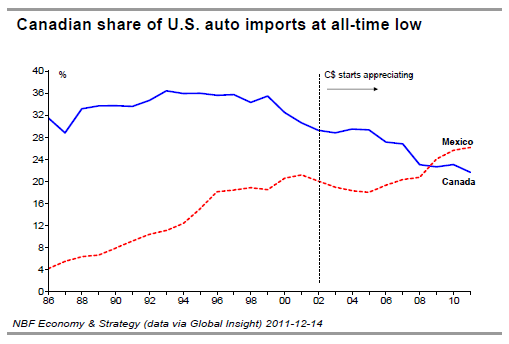

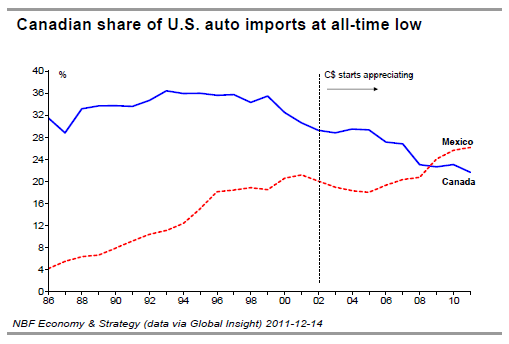

The erosion of Canada’s manufacturing base is one explanation for that alarming trend which is likely to extend into 2012. The poster child for this sad reality is the auto sector. After rebounding strongly in the preceding year, the Canadian auto sector struggled in 2011. Of course, supply chain disruptions related to the Japanese tsunami played a role there, but the negative impact of the strong currency cannot be ignored. In 2011, Canada’s share of the US auto market fell under 22% for the first time on record.

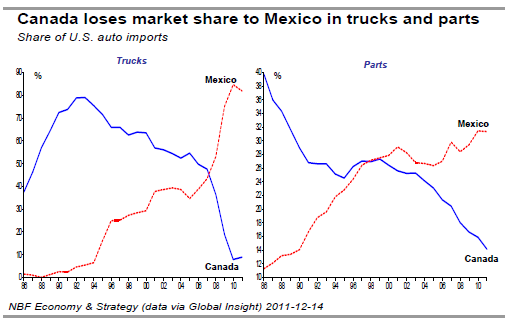

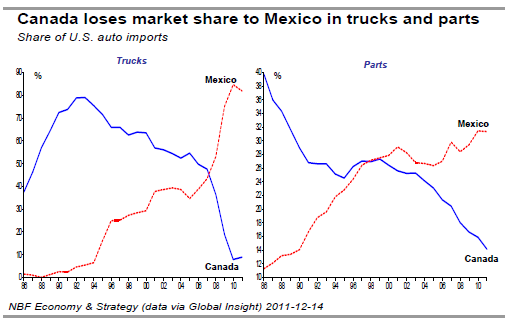

Low-cost competitors with highly competitive currencies, like Mexico, have grabbed market share particularly in high margin segments like trucks and parts. While over half of overall US truck imports came from Canada in 2002, our market share in that segment has shrunk to just 10% today. Mexico’s share, in contrast has soared past 80%. The contrast is less dramatic for the auto parts business, although the trend is similarly depressing from a Canadian standpoint.

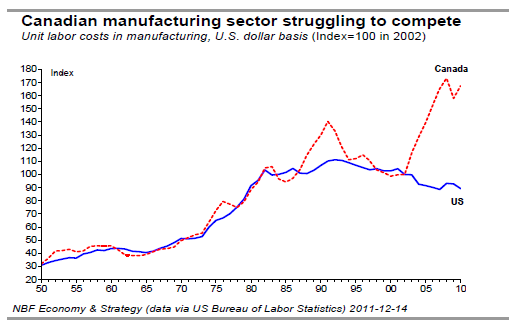

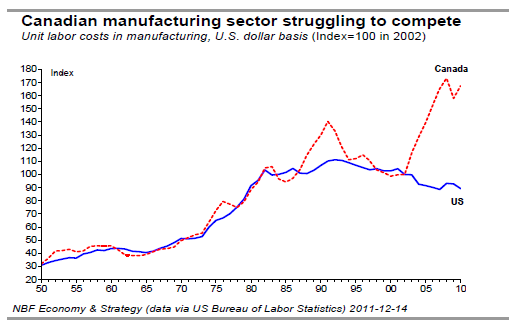

The only segment where Canadian exporters have been able to maintain market share was in the passenger car segment, although that too could change for the worse sooner rather than later. For instance, note a recent comment from Chrysler’s CEO Sergio Marchionne: “you cannot have an uncompetitive wage rate and then expect Chrysler or all the other car makers to keep on making cars in this country and be disadvantaged”. He has a valid point. While Canadian manufacturing costs have tracked US ones closely up to 2002, the gap has widened significantly since then, due to the Canadian dollar’s ascent.

And with the US dollar expected to remain weak over the next several years, and commodities continuing to inflate the loonie, salvation for Canada’s auto sector can only come via higher productivity. In fact, such a prescription applies to pretty much all of the non-resource sector. Canada is on track to improve its productivity record if recent trends in business investment are any guide, but productivity improvements won’t happen overnight. So expect non-resource exporters to remain under pressure over the near to medium term as they compete with lower-cost competitors. That said, the acceleration of the US economy should be enough as to allow trade to turn into a contributor to growth in 2012. Indeed, a rising tide tends to lift all boats, even those that are listing badly.

The contribution from trade will be offset by a weakened domestic demand resulting in tepid GDP growth of just 2% for Canada in 2012, taking away our bragging rights of having outperformed the US economy since 2006. With domestic demand under pressure and the European debt crisis having the potential to spiral into a full-blown global financial crisis, the Bank of Canada is likely to play safe and delay rate hikes to 2013.

The cyclical rebound from the economic and financial crisis of 2008-09 turned out to be short-lived. We estimate 2011 global economic growth at 3.9%, the lowest since 2003, excluding the last recession. A number of headwinds arose in the first half of the year. Strong inflationary pressures, notably in energy and food, crimped consumer purchasing power around the world. In many countries, mainly those whose labour markets have been slow to recover, income gains have barely matched inflation. Consumer spending has slowed accordingly. Then Japan was struck by a tsunami that destroyed much of its industrial plant and disabled global supply chains for months. Though these factors are unlikely to affect growth in 2012, euro-zone public finances will remain the focus of investor attention.

In Europe, the crisis that began in the spring of 2010 with worries about the solvency of Greece has ended up spreading throughout the zone. European leaders have been unable to agree on action that would limit investor apprehensions to the worst-off of the euro countries. The default swap market registers fears about Italy greater than those about Greece in April 2010. The soaring cost of Italy’s borrowing is made especially perilous by the country’s high debt load. The upshot is that stabilizing its debt-to-GDP ratio will take measures much more drastic than initially foreseen.

In our view, the size of Italy’s debt and its importance in the European banking system require that the authorities keep its financing costs sustainable, especially since Italy, unlike Greece and Portugal, is generally regarded as solvent. Things would probably not have reached this pass had European leaders not done too little, too late as investor apprehension mounted. Economists have long insisted that monetary union is not viable without fiscal union. There has been real progress recently, not least in a plan to improve the Stability and Growth Pact that would entail a loss of fiscal sovereignty for member countries whose deficits or debt exceed set limits. To survive, however, we think the euro zone must ultimately go further, harmonizing its economic and social policies on a model more favourable to growth and more sustainable in the long term. In the meantime, further short-term measures will also be necessary to limit the financing costs of Spain and Italy. Since insufficient funds are available to bail out these countries, it seems increasingly clear that the rescue of the euro zone will require issuance of eurobonds, ECB purchases of new bond issues, or both.

For the euro economies, the damage has been done. Most countries of the zone are being forced to eliminate their deficits much faster than they had planned. The resulting across-the-board fiscal austerity is likely to plunge the zone into its second recession in less than four years, especially since the climate of uncertainty has undermined household and business confidence. Industrial production has been in decline for two months now and retail sales are down from a year ago. These conditions could exacerbate pressures on governments and financial institutions as they wrestle with their heavy indebtedness. In our view, however, the central banks have the tools in place to move quickly to prevent the economic downturn from becoming a financial crisis.

Even Germany, whose austerity measures need not be as sweeping as those of other euro countries, is unlikely to come through unscathed. Germany exports a hefty 12.6% of its GDP to other euro countries. The euro zone’s neighbours may also feel the shock waves. The U.K., already facing an outlook of slow growth in its domestic economy, will grow hardly at all if its major trading partners stumble. The Chinese and U.S. economies, on the other hand, are much less exposed. Their exports to the euro zone amount to only 4.0% and 1.2% of GDP respectively. So if European governments and central banks can stop their recession from turning into a credit crunch, the two heavyweights of the global economy will pull through.

The scope of the austerity that will grip the advanced economies in 2012 can be seen in IMF projections of changes in structural deficits, illustrating the effect of discretionary changes to government budgets as of September. At that time the IMF considered that the braking effect of fiscal policy in the advanced countries would be the sharpest since it began compiling the data in 2002 – 40% sharper than in 2011. And it is quite possible that the fiscal braking will be even more severe than expected, since countries including France and Italy have adopted additional austerity measures since September.

The watch list includes, besides governments, the real estate sectors of the advanced economies. The housing market is exposed to additional risk as a number of countries go into recession. We are especially surprised to see 16 of the 22 OECD countries for which data are available reporting deflation of real home prices in the most recent quarter for which data are available. One reason is that the demographics of European countries including Germany, Spain and Italy are unfavourable

to real estate – the ranks of their first-time homebuyers are depleting sharply. This trend, combined with a euro-zone labour market that is especially hard on young people, suggests to us that the housing sector in some advanced countries may remain under pressure over the coming quarters.

As the euro economy deteriorates, the U.S. economy has been gaining strength. The Citigroup Economic Surprise Index for the U.S. recently approached its most positive reading ever. We are especially comforted by improvements in the labour market at a time when an unusually divided political landscape has generated high uncertainty about fiscal policy. Despite these risks, we see the U.S. economy accelerating to growth of 2.5% in 2012 after a difficult 2011 (see U.S. section for details). As for the emerging economies, which bulk ever larger in the world economy, current indicators are essentially in line with the consensus expectation.

World industrial production, meanwhile, is still trending up, mainly as a result of a surge in the emerging economies. However, recession in Europe is likely to slow imports from Asia. A recent deceleration of China’s economy aroused apprehension, though the 9.1% growth rate of its third quarter would be the envy of almost any other country. It should be kept in mind that to counter inflation, Beijing has considerably reduced its monetary accommodation in an attempt to cool its economic growth rate to about 8%. However, the anticipated sluggishness of the advanced economies in 2012 is likely to slow China’s growth to a rate below that threshold.

In that event, Beijing can be expected to offset export softness by stimulating domestic demand, especially since recent reports show a sharp deceleration of consumer prices. The recent decline of commodity prices, in response to a decline of physical and financial demand and to the rise of the U.S. dollar, will ultimately show up as disinflation. If the economic picture deteriorates further, inflation fears will completely dissipate and a number of central banks, especially in emerging countries, could put their shoulders to the wheel. In the advanced countries, real short rates are now more stimulative than in 2008. In addition, several central banks use unconventional monetary stimulus currently.

All these factors considered, we see the advanced economies taken together as likely to expand 1.3% in 2012. Outside the great recession of 2008-09, that would be the weakest annual growth of the last 30 years. Yet the emerging economies, given their growing share of world output, are likely to push global growth to 3.4% in 2012.

From 1980 to 2000, the advanced economies accounted for 63% of global growth. Since 2000 they have accounted for 28%. This new reality justifies optimism in the face of old-world difficulties.

U.S.: Accelerating growth in 2012

It’s now clear that the U.S. economy not just avoided recession in 2011 but in fact accelerated as the year progressed. GDP in Q4 is tracking well above 2% annualized, the best quarterly performance of 2011. Momentum should carry through to 2012, with the US achieving above-potential growth for the first time in six years, helped by resilient domestic demand and inventory rebuilding. The big caveat, however, is that a European-triggered global financial crisis is averted by policymakers who would, presumably, have learnt about the devastating costs of inaction à la 2008.

Consumers finding support

The U.S. economy has rarely done badly when its consumers have been in a spending mood. Its acceleration in the second half of 2011 was largely a result of consumers getting their mojo back. With two months in, Q4 real retail spending is tracking + 6.3% annualized, the highest since Q4 of 2010. Retail volumes in the second half of 2011 are on track to grow at twice the pace of the first half.

The outlook for 2012 consumer spending seems positive, partly because of a slower pace of deleveraging. Mortgage credit outstanding continues to drop, but more slowly than before. In Q3, moreover, non-mortgage credit (even excluding student loans), led by auto loans, showed the first quarterly increase in three years. Together with a stabilization of the savings rate, these are signs that the worst of the deleveraging process may be over.

Another plus for consumer spending is the recovery now under way in employment. Non farm payrolls rose 681,000 from June through November, with all gains coming from the private sector. The household survey also shows a clear improvement in the labour market – full-time employment up 759,000 over the same period. In November more than 113 million Americans were employed full-time, the most since April 2009. Odds are that the uptrend will extend into the new year, particularly given the strength of helpwanted listings, which tend to lead the household employment survey.

Complementing the improvement in credit and the labour market in 2012 will be a diminished drag on consumer spending from the negative wealth effect of home prices.

Has housing finally hit bottom?

While it’s too early to say whether the double-dip housing recession is definitely over, there are signs suggesting some stabilization ahead. Residential investment grew in both Q2 and Q3, the first back-toback quarterly increases since 2005. The pace of home-price deflation seems to be moderating as supply and demand come into better balance. Thanks to lower mortgage rates and depressed home prices, affordability is the best in a generation. That, coupled with an 18-year low in the financial obligations ratio, makes borrowing more likely.

Moreover, higher rental demand has driven rents high enough as to give renters incentives to become home owners. On the supply side, while inventory remains large, the drop in foreclosure rates is also helping somewhat in keeping supply growth under control. The overall improving market conditions explain perhaps why builder confidence in December was the second highest since 2007, according to the National Association of Home Builders. That said, don’t expect a significant turnaround in the housing market just yet. A flattish trend is more likely for home prices in 2012, with improving demand likely to be offset by supply increases from both new construction and foreclosures that have yet to hit the market. But importantly, the reduced drag from housing should be supportive of consumption spending in 2012.

Business investment to remain solid

Domestic demand is likely to gain further support in 2012 from investment spending as businesses seek to maintain the growth of productivity and profits. Though U.S. output is now back to pre-recession levels, employment remains 5% or so below the prerecession peak. In short, the U.S. is doing more with less. This productivity boost has come from massive capital outlays over the last couple of years, with investment in equipment and machinery now back to pre-recession levels after growing 15% in 2010 and roughly 10% in 2011. Given the solid corporate profits of 2011 and the usual lag between profits and investment, there is reason to expect capital spending to continue at a healthy pace in 2012, particularly if global economic uncertainty dissipates somewhat.

economy was subjected to a near government shutdown in April, a debt-ceiling drama and the ensuing US credit downgrade by S&P in July/August, and the failure of the Super Committee in November. December saw further debates and footdragging by Congress on what ought to be a straightforward decision on the extension of payroll tax cuts. The fiscal outlook remains unclear. Assuming nothing else changes on Capitol Hill (and the current political impasse suggests just that outcome) the US economy will face $2.1 tn in spending cuts over ten years. Add to that the end of the Bush-era tax cuts and the potential fiscal drag rises to over 2% of GDP in 2013. Facing the prospect of a recession-inducing fiscal drag, a new Congress after the 2012 Presidential elections will very likely kick the can down the road.

The inventory cycle to boost 2012 GDP

Having braked growth in 2011, inventories are set to contribute to it in 2012. Destocking has chopped 3.3% off GDP in the last four quarters alone (Q410 to Q311), the largest 4-quarter cumulative drag outside of a recession in 25 years. Now, unless we’re in a recession or heading precipitously towards one, such inventory cuts are unsustainable. In our view, with domestic demand seemingly still resilient, it’s a question of time before the restocking process kicks back into gear. History suggests there tends to be a couple of quarters lag in the inventory response to changes in final sales.

So, the surge in final sales in Q3 bodes well for inventory rebuilding over the next few quarters, assuming of course that the global economic picture doesn’t darken any further.

Trade supported by a competitive US dollar

The resilience of domestic demand will be especially welcome in 2012 as global growth slows. Trade may face some headwinds as a European recession translates into sluggish demand for American exports. That said, the overall impact on US growth isn’t likely to be significant, particularly given that only 20% or so of US exports go to Europe, and exports account for less than 14% of the overall US economy. Moreover, the highly competitive U.S. dollar, which in real terms is still near historic lows, will provide some offset, especially in markets of buoyant demand such as Asia and South America.

Further down the road, exports are set to benefit from the long-term trend of depreciation of the U.S. dollar. On trade fundamentals alone, the greenback needs not depreciate much more: the trade deficit excluding petroleum is stabilizing at just 1.5% of GDP. Depreciation pressures will come from elsewhere – the country’s precarious fiscal position, the Fed’s easy money policy, China’s reduction of its foreign exchange reserves. We see the USD losing ground against most currencies, primarily the yuan and the OPEC currencies if the latter are allowed to come off the peg.

crisis, perhaps via sovereign defaults. According to data from the Bank of International Settlements, US exposure to European banks stood at US$3.8 tn at the end of Q2. Taking into account derivative contracts, guarantees and credit commitments, the exposure rises to roughly US$5.9 tn. Although the bulk of that is being held by the nonbank private sector, the banking sector also has significant exposure (over US$700 bn). No wonder that CDS spreads for American financials have risen

in tandem with European ones as the debt crisis intensified on the old continent. Should European debt turn sour, expect US banks to take write-downs triggering balance sheet repairs via recapitalizations and asset sales. That eventuality – a credit crunch – is the major channel through which Europe could affect the United States.

QE3 in 2012?

Fortunately, the US has a more proactive central bank than Europeans do. While an improving US economy and better credit flow make a third round of unsterilized bond purchases (QE3) less necessary at this point, a European-triggered credit crunch would have the Fed take prompt action. The recent easing in inflationary pressures, with both the CPI and PPI on a declining path, and stable inflationary expectations, give the Fed more room to act if necessary. Note that even with the currently wellfunctioning financial markets, FOMC members continue to talk about the possibility of unleashing QE3 as a way of stimulating the economy. Should credit markets freeze à la 2008, expect talk to translate into action.

All told, barring a European-triggered global financial crisis and subsequent world recession, US economic growth should accelerate to an above-potential 2.5% in 2012 thanks to a combination of resilient domestic demand and inventory rebuilding. Fiscal drag will continue to impose a speed limit on the economy in 2012, although that will pale in comparison to the impacts seen in 2013 and beyond.

Canada: Headwinds from several fronts in 2012

Facing challenges both at home and abroad in 2012, Canada stands to underperform the US for the first time in six years. Domestic demand will be under siege from a likely softening in housing, and a more moderate pace to consumption spending. Trade will be vulnerable to the lagged impacts of a strong Canadian dollar although there will be some offset in the form of increasing demand from an accelerating US economy. With domestic demand treading water and European inertia threatening to trigger a global financial crisis, the Bank of Canada is likely to delay rate hikes to 2013.

Labour market deceleration in 2012

Canada’s labour market recovery has been much stronger than that of the US, with employment here now above the pre-recession peak compared to American payrolls still languishing 5% below prerecession levels. The difference between the two countries has, of course, been the relatively better economic growth in Canada. But government payrolls have also been a big driver in boosting Canadian employment. Over the last three years (Oct08 to Nov11), Canada has added roughly 164,000 jobs, 95% of which came from government. Contrast this with the US where the purge in public sector payrolls has been unprecedented. The increase in hiring by government together with the 278,000 job gains in private sector service-producing industries lifted total services employment enough as to offset the purge in the goods sector payrolls.

The employment slump in the goods sector was driven by the manufacturing sector whose payrolls are at a record low. This avalanche of pink slips from factories was partially offset by the uptrend in construction employment which reached new highs in 2011.

What do those patterns suggest for the 2012 employment? Simply put, those trends aren’t bullish. The destruction of manufacturing jobs is symptomatic of a structural problem that’s not going away anytime soon (C$ impacts are described further on). And the gains in construction jobs which have been fed by stimulus programs and the expansion of housing, are likely to reverse as both of those boosters fade in 2012. Hiring in the resources sector may provide some support, although the expected softening in commodity prices should limit employment gains there. In any case, any job gains in the resources sector, which accounts for less than 10% of overall goods sector employment, are unlikely to have a significant positive impact. So expect the goods sector payrolls to remain weak.

This time, however, there won’t be as much of an offset from services payrolls. Government hiring at the pace seen over the last three years isn’t sustainable, nor likely to be permitted to continue particularly with deficit-cutting plans underway. The saving grace for Canadian employment in 2012 may be from private sector service-providing sectors, but even there we’re not expecting miracles given the anticipated softening of the overall economy. All told, employment growth should be modest at just under 1% in 2012, contrasting with a roughly 1.5% increase in the prior year. That should leave the unemployment rate averaging north of 7% in 2012.

Consumers under stress

A tepid labour market will evidently weigh on consumption spending in 2012. However, a slower global economy should cap gasoline prices which will offer Canadians some relief. That’s pretty much the reverse of the scenario that played out in 2011 when the benefits of a relatively strong labour market on consumption spending was offset by high gasoline prices. Another difference will be the impact of the housing market on consumers. For now the Canadian housing market is being described as

“balanced” with the listings-to-sales ratio remaining low enough as to allow home prices to rise at a modest pace.

But with the labour market likely to decelerate, the resulting weakness in household incomes should work as to bring the existing home market closer to buyers’ market territory, hence limiting price increases or even prompting price declines in some cases. The market for multiple units e.g. condos, apartments, seem more prone for a price correction given how far new supply has strayed from that of singles.

So the housing wealth effect which has helped boost consumption spending over the last several years is likely to be less of a factor going forward.

How serious is the deleveraging threat to consumption spending?

We are less concerned about the negative impacts of deleveraging on consumption because we do not expect the savings rate to rise significantly given that interest rates are set to remain low for a while. Rock bottom interest rates are clearly discouraging savings and encouraging debt accumulation.

The Bank of Canada is in a bind because it’s being forced by global events to keep interest rates low, hence fueling the debt accumulation spree of Canadians. In fact, the longer the BoC delays rate increases, the harder it will be for it to raise rates without triggering a housing-led recession. Which is why the BoC felt that it had to, repeatedly, warn Canadians against over-leverage, going so far as to say that “Canadians are now more indebted than the Americans”. While the latter statement may be true if one looks at an unadjusted ratio of household debt to disposable income which is indeed higher in Canada, the comparison is arguably unfair. Disposable incomes of Americans aren’t exactly comparable to Canadian ones since the former get a lot less bang for the buck having to assume more significant expenses like health care outlays. An adjusted ratio, which removes health care expenses from the calculations, shows that Canadians aren’t quite as levered as Americans.

That said, there’s no denying that the Canadian debt picture isn’t pretty. Canadians will find it harder to service their debt once interest rates resume their ascendancy. But rates are set to remain low over the next several years, meaning that debt servicing costs should remain manageable over the near to medium term. Deleveraging would become a more serious problem for consumption spending if interest rates rise quickly or if the housing market collapses. We’re not expecting either of those to materialize. Still, consumers will face enough challenges as to limit spending growth to less than 2% in 2012.

Providing a partial offset in 2012 to a flatlining housing market and the anemic growth in consumption and government spending, will be business investment spending. Buoyed by strong corporate profits, low interest rates and a strong Canadian dollar, business outlays have decent fundamentals for expansion. Planned outlays relating to projects in energy, namely hydro and the oil sands will also help support investment. That, however, won’t prevent overall domestic demand to ramp down to a sub-2% performance in 2012.

Canadian Trade: Currency impacts offset by accelerating US economy

With the US economy going up one gear in 2012, demand for Canadian exports should improvesomewhat. However, it’s not going to be smooth sailing for our exporters. With only 5% or so of their products going to Europe, Canadian exporters are lucky to not have significant direct exposure to waning demand from the old continent. However, exporters of resources, will feel an indirect hit as the European recession weighs enough on global growth as to bring down commodity prices. Non-resource exporters may get some lift from an accelerating US economy but will be hampered by the lagged impacts of a strong Canadian dollar. Note that the merchandise trade balance remained in deficit territory for the third year in a row in 2011. And, as has been the case for seven of the eight preceding years, trade was likely again a drag on the economy in 2011. So the currency’s impacts can be significant.

Commodity prices, which are largely determined on global markets, have been on the rise over the past several years courtesy of the growing clout of emerging markets in the world economy, fuelling the Canadian dollar’s ascent. While higher prices have allowed our resource exporters to cushion the blow of the stronger currency, non-resource exporters haven’t been so lucky. In fact, excluding resources, Canada’s trade performance has been largely disappointing, with the non-energy trade balance on a steady decline in recent years.

The erosion of Canada’s manufacturing base is one explanation for that alarming trend which is likely to extend into 2012. The poster child for this sad reality is the auto sector. After rebounding strongly in the preceding year, the Canadian auto sector struggled in 2011. Of course, supply chain disruptions related to the Japanese tsunami played a role there, but the negative impact of the strong currency cannot be ignored. In 2011, Canada’s share of the US auto market fell under 22% for the first time on record.

Low-cost competitors with highly competitive currencies, like Mexico, have grabbed market share particularly in high margin segments like trucks and parts. While over half of overall US truck imports came from Canada in 2002, our market share in that segment has shrunk to just 10% today. Mexico’s share, in contrast has soared past 80%. The contrast is less dramatic for the auto parts business, although the trend is similarly depressing from a Canadian standpoint.

The only segment where Canadian exporters have been able to maintain market share was in the passenger car segment, although that too could change for the worse sooner rather than later. For instance, note a recent comment from Chrysler’s CEO Sergio Marchionne: “you cannot have an uncompetitive wage rate and then expect Chrysler or all the other car makers to keep on making cars in this country and be disadvantaged”. He has a valid point. While Canadian manufacturing costs have tracked US ones closely up to 2002, the gap has widened significantly since then, due to the Canadian dollar’s ascent.

And with the US dollar expected to remain weak over the next several years, and commodities continuing to inflate the loonie, salvation for Canada’s auto sector can only come via higher productivity. In fact, such a prescription applies to pretty much all of the non-resource sector. Canada is on track to improve its productivity record if recent trends in business investment are any guide, but productivity improvements won’t happen overnight. So expect non-resource exporters to remain under pressure over the near to medium term as they compete with lower-cost competitors. That said, the acceleration of the US economy should be enough as to allow trade to turn into a contributor to growth in 2012. Indeed, a rising tide tends to lift all boats, even those that are listing badly.

The contribution from trade will be offset by a weakened domestic demand resulting in tepid GDP growth of just 2% for Canada in 2012, taking away our bragging rights of having outperformed the US economy since 2006. With domestic demand under pressure and the European debt crisis having the potential to spiral into a full-blown global financial crisis, the Bank of Canada is likely to play safe and delay rate hikes to 2013.