Standard & Poor’s made a splash early in the year with its downgrade of the credit of nine euro countries. The markets were little moved by its pronouncement, an indication that investors had for the most part already factored in the agency’s view. At this writing, the initiatives announced by European leaders do not seem to be enough to end the crisis, especially since recession will further worsen Europe’s public finances. Fortunately, the economies of the U.S. and of emerging countries are likely to offset the European downturn.

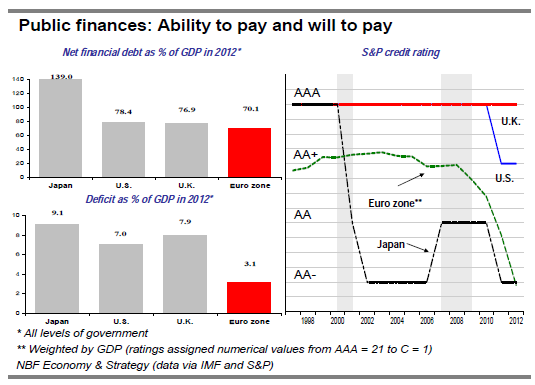

In assessing a borrower’s creditworthiness, rating agencies weigh a company’s or a government’s ability to pay. But for government there is another twist: its will to pay must also be weighed. Historically, the indebtedness and financial stress of defaulting sovereign states have varied greatly, an indication that context and political institutions play an important role in such situations. A political entity may be able to remedy the situation but lack the will to do so. This is the idea behind S&P’s explanation of its downgrade of the nine euro countries: “Today’s rating actions are primarily driven by our assessment that the policy initiatives that have been taken by European policy makers in recent weeks may be insufficient to fully address ongoing systemic stresses in the eurozone.” Thus although the euro zone has a smaller debt burden than the U.K. and less than half its forecast deficit, the credit rating of the zone as a whole is now three notches below that of its offshore neighbour (top chart). It is two notches lower than that of the U.S. and equal to that of Japan, though the latter’s financial position is at first sight much more fragile.

A sad finding, but the position of the euro zone is not hopeless. Its member countries must contemplate a greater degree of cooperation to overcome the crisis. Their governments must go beyond the announced plan to impose sanctions on countries lacking fiscal discipline and to harmonize their tax regimes. In our view, the salvation of the zone also lies in convergence of social and economic policies toward a model geared to economic growth. And if member countries agree to issue bonds jointly, taking advantage of the relatively good financial shape of the zone as a whole, the crisis will be over.

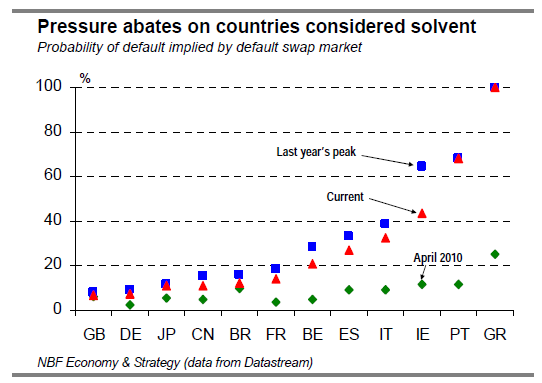

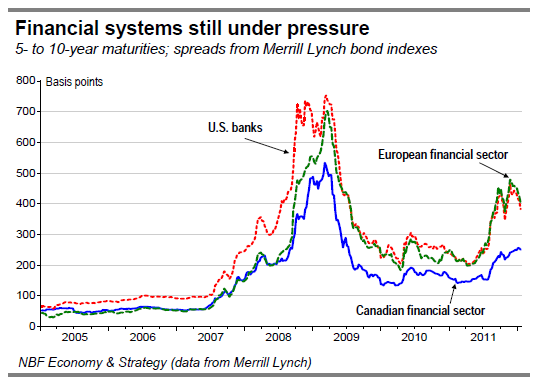

As noted above, S&P’s multiple downgrades did not exacerbate pressures on euro-zone governments and institutions. For Greece and Ireland, the countries considered insolvent, fears remain at a peak. For the other countries in difficulty, fears are below last year’s peak (chart, below). By offering banks attractive terms for three-year money, the ECB has eased pressures on the European financial system.

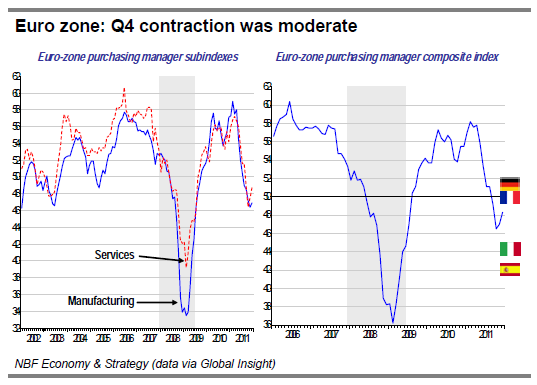

Europe’s crisis of public finances that began in the spring of 2010 has entered a new phase. The euro zone probably slipped into recession in the last quarter of 2011. Yet the contraction is unlikely to have been sharp – the consensus expects 0.6% annualized. Though purchasing-manager indexes show a retreat in manufacturing since August and in services since September, the amplitude is nothing like that of 2009. And the two indexes rebounded slightly in December. But some countries could take a bigger hit than others. The indexes for France (at a four-month high) and Germany (a three-month high) suggest stagnation of output rather than contraction, while those for Spain and Italy are sharply negative (chart, below).

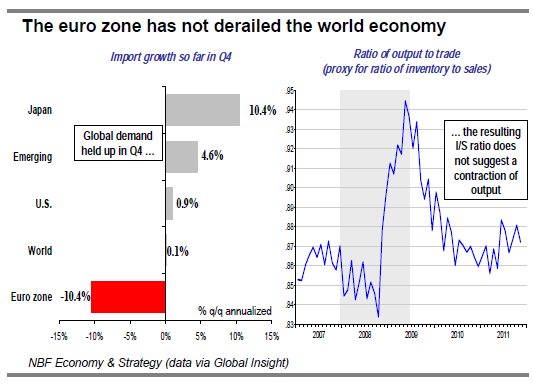

Meanwhile, indicators remain encouraging for the global economy as a whole. The CPB reports a 1% rebound of world trade in November, the first increase in three months. While euro-zone imports were down 10.4% annualized in Q4 (after two months of data for the quarter), global imports were virtually flat as a result of strong demand from Japan and emerging economies. Since industrial production was basically flat from September to November, the ratio of output to trade (which is a proxy for manufacturing inventory imbalances) is far from the excess that could trigger a contraction in production.

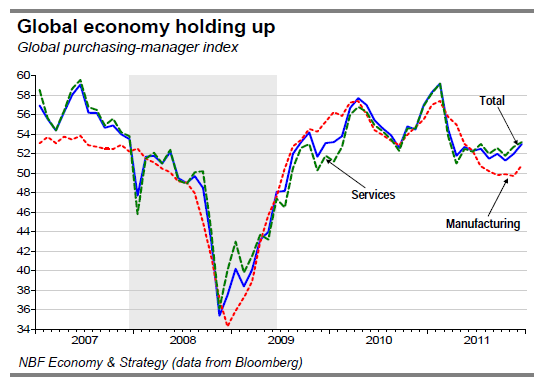

The JPMorgan Global purchasing-manager index also shows the world economy cooling but still expanding. Corroborating CPB data on industrial production, its manufacturing index was barely below 50 from September to November, an indication of flat output. In December it rose to 50.8, the highest since last June. Its service index also rebounded in December, to a nine-month high of 53.2. The two rises together took the composite index up one point in December, the strongest gain in 11 months.

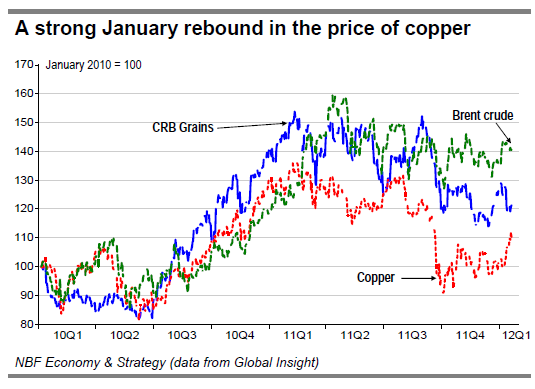

The recent run-up of copper prices is also reason for optimism. It shows sustained demand for a metal with many industrial uses. Risk aversion and fears of a global slowdown drove its price down 31% between August and October. The rebound of the past month has taken it back to the level of September 20th. As for oil, its price held up in the second half of 2011 despite an uptick in fears of global recession. In addition to geopolitical concerns that have supported the commodity price most recently, global demand also played a role. An easing of oil prices would have meant an immediate boost to consumer purchasing power, but it was not to be. Household food bills, however, are likely to benefit from a significant drop in grain prices.

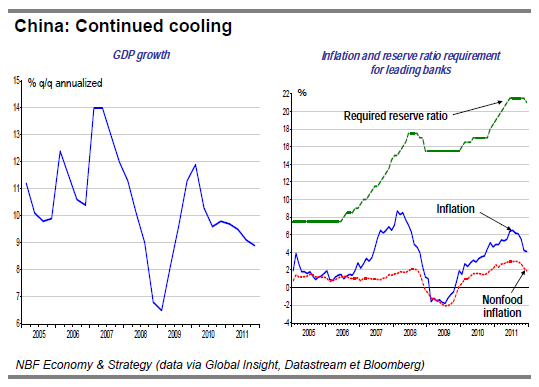

With fear of inflation supplanted by fear of slowdown, the central banks of emerging countries have begun to backpedal from their withdrawal of accommodation, Brazil’s and India’s are seeking to stimulate domestic demand to offset a drop in exports to Europe. China’s central bank, seeing inflation abate, reduced its bank reserve requirement in early December. Despite the worries about China’s slowdown, it is a soft one so far. Growth slipped from 9.1% annualized in Q3 to 8.9% in Q4. We expect further cooling in 2012, to an average rate of 7.9%, a soft landing by any measure. Note that unlike the OECD, China has ample room to loosen monetary policy to stimulate its economy further if needed.

In short, recent indicators reinforce our belief that despite a European recession, the economies of the U.S. and of the emerging countries should be able to help the global economy grow at 3.4% this year, if a global financial crisis can be averted.

U.S.: Taking off, finally

As Europe flounders, hope for supporting the global economy rests once again of the U.S. There is reason to be optimistic. U.S. consumers, the main driver of the world’s largest economy seem to have got their mojo back thanks to an ascending labour market. Housing is stabilizing and fundamentals for business investment are good. Healthy domestic demand will be supplemented by a highly competitive export sector, presenting the U.S. with the opportunity to achieve above-potential growth for the first time in six years.

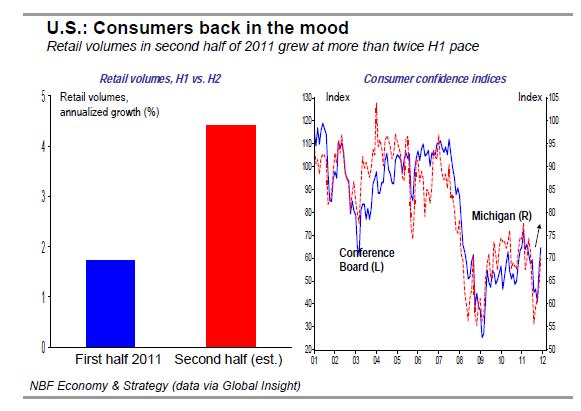

Left for dead just a few months ago (remember the ubiquitous talk of recession?), the resilience of the U.S. economy has surprised yet again. Fourth quarter GDP growth printed 2.8% annualized, the best performance of 2011. The resurgence of the U.S. economy has much to do with its largest component, consumption. Rising household confidence has been self-fulfilling: retail sales grew more than twice as fast in the second half of 2011 as in the first half.

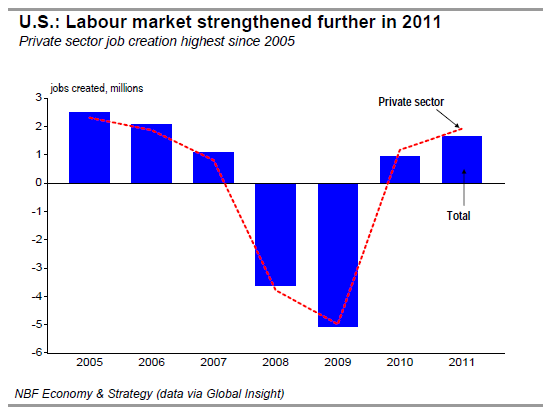

The newfound confidence was likely spurred by improvement in the labour market. Including December’s triple digit gains, the U.S. economy indeed added 1.9 million private sector jobs last year, the highest annual tally since 2005. With initial jobless claims falling to a four-year low in early January, momentum in the labour market likely carried over to 2012. That together with the extension of payroll tax cuts through February can be expected to boost consumer spending.

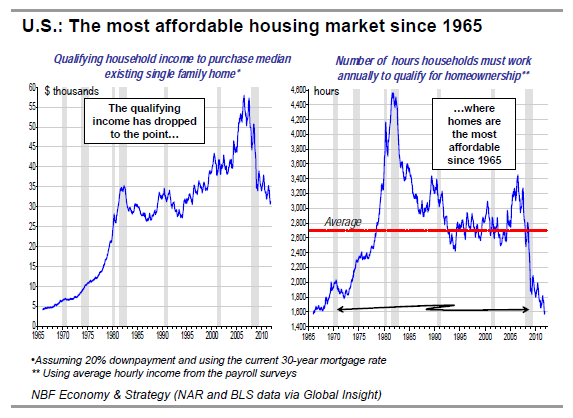

Stabilization of the housing market is also helping. In the lead-up to the great recession of 2008-09, the negative wealth effect of the collapse of the housing bubble had a disastrous impact on consumption. While we do not rule out further declines in the near term, home prices may find a floor in 2012. Demand fundamentals are good, thanks in part to the uptrending labour market but also because housing is the most affordable in decades. With interest rates and home prices in the basement, the qualifying income has dropped enough to make the purchase of a home much easier. Moreover, higher rents make purchasing a home relatively less costly than renting in many cases. Supply fundamentals are a bit harder to gauge given the foreclosures that may or may not hit the market in coming months. But current data show the smallest inventory of homes for sale since 2006.

The multi-year low in supply is true across most types of housing – single homes and multis. No wonder the confidence index of the National Association of Home Builders rose in January to the highest level since mid-2007. So, after acting as a drag on consumer spending, housing may be about to add lift to the economy.

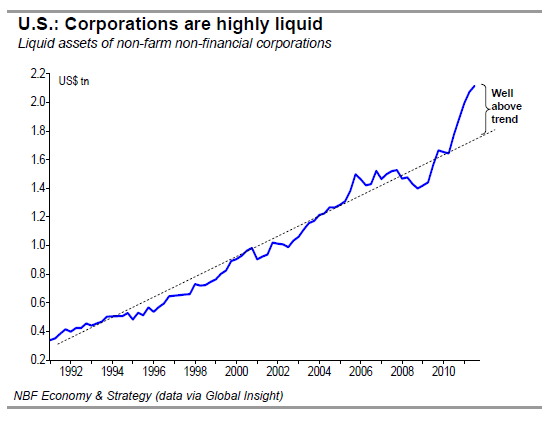

Domestic demand stands to benefit from business capital spending as well as from consumption and residential construction. While investment spending moderated in Q4, the outlook for that important component of GDP is promising. The strong profits of recent quarters are likely to boost investment once the cloud of uncertainty dissipates. Moreover, U.S. corporations are highly liquid and it’s just a matter of time before that pile of cash, which incidentally earns near-zero interest, is directed towards more productive investments as firms seek better returns. Investment in latest technology and machinery is necessary since firms depend on productivity improvements to compete against global competitors, several of whom arguably benefit from their country’s undervalued currencies. The drive towards productivity enhancements is already paying off for exporters, which now account for a record high 14% of U.S. GDP. Barring a global recession, the trade sector should remain a strong contributor to the U.S. economy.

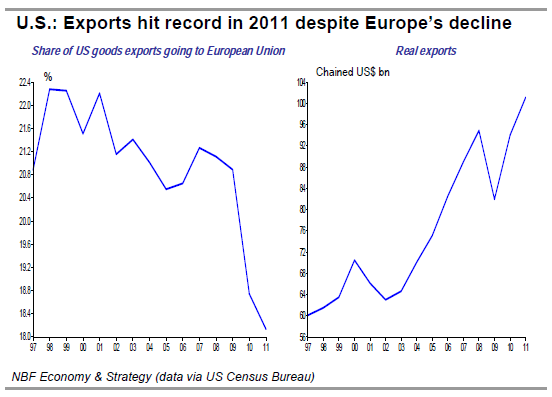

While the European recession won’t help, U.S. trade is likely to remain a strong performer. In fact, U.S. exporters are becoming less and less reliant on the European market, with the latter’s share of U.S. goods exports falling to the lowest in decades. Export volumes which hit a new record in 2011 should continue on their uptrend this year, helped primarily by emerging markets.

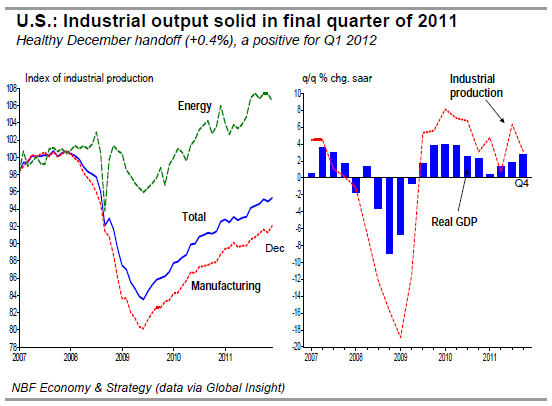

The biggest risk to the U.S. economy, besides a European-triggered global financial crisis, is domestic politics. After 2011’s annus horribilis for U.S. Congress, with a near government shutdown, an acrimonious debt ceiling debate and political bickering, which ultimately gave S&P no choice other than downgrade the U.S. credit rating, the political impasse is unlikely to wind down. That said our base case scenario includes the extension of the payroll tax cuts through year-end, something that would be deemed popular in an election year. With the domestic economy and trade both in relatively good shape, expect the strong showing of industrial output in the second half of 2011 to extend into the new year, taking the U.S. to above-potential growth in 2012 for the first time in six years.

Canada: Shifting to a lower gear

While the U.S. economy seems headed toward cruising speed, Canada’s is shifting down a notch. Although recent data have been generally bearish, that does not necessarily portend to another recession. A moderation in growth was expected in the final quarter of 2011, particularly after Q3’s hot pace. And the consistently bad news from Europe has evidently affected both consumer and business sentiment. There is nonetheless reason to be optimistic, especially in light of the apparent resurgence in the economy of our main trading partner.

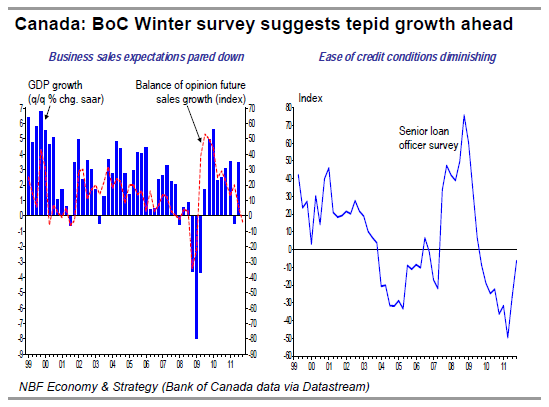

Is Canada headed for recession? Recent data have certainly been weak enough to raise the spectre of another downturn. The labour market is sputtering and despite low interest rates, business investment and construction are contracting. The Bank of Canada’s latest Monetary Policy Report presented a pared-down outlook for 2012. Its recent Business Outlook Survey was even bleaker, with the balance of opinion about the future sales growth of domestic firms turning negative for the first time since the recession. Respondents to the survey also reported diminished ease of credit, with the balance of opinion the worst since the recession. This pessimism is bad news for GDP because sales expectations tend to lead economic growth. Yet these expectations – arguably influenced by the European sovereign-debt crisis – do not preclude a positive print for GDP growth and remain consistent with our call of a tepid expansion of 2% annualized over the period 2011Q4-2012Q1.

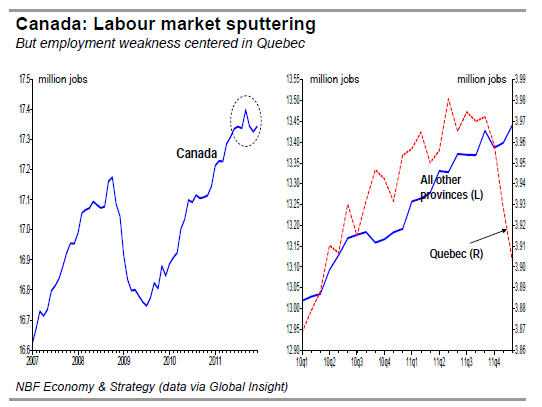

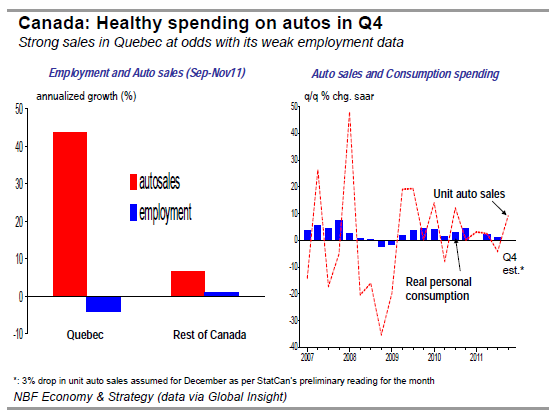

The sputtering labour market is of course another concern. Its weakness has been concentrated in Quebec; in the rest of Canada employment has continued to grow. The Quebec data are at odds with other indicators for the province, notably retail sales and unit auto sales. The latter soared well over 40% annualized from September to November, a period in which the Labour Force Survey reported employment contracting 4% annualized in Quebec. Compare that with the rest of Canada which saw employment grow roughly 1% annualized over the same period but with real auto sales expanding at less than 7% annualized.

The overall strength of Canadian auto sales bodes well for consumer spending in Q4. The gap in auto sales between Quebec and the rest of Canada is too wide to be explained entirely by Quebecers bringing their purchases forward to beat the January increase in QST. When job prospects take a turn for the worse, consumers tend to defer purchases of durable goods.

So the Quebec employment report is puzzling, particularly given what’s happening in the rest of Canada. That said, one shouldn’t be complacent, and we’ll be watching closely to see if Quebec employment catches up with the rest of Canada or, worse, if the other provinces follow Quebec’s decline.

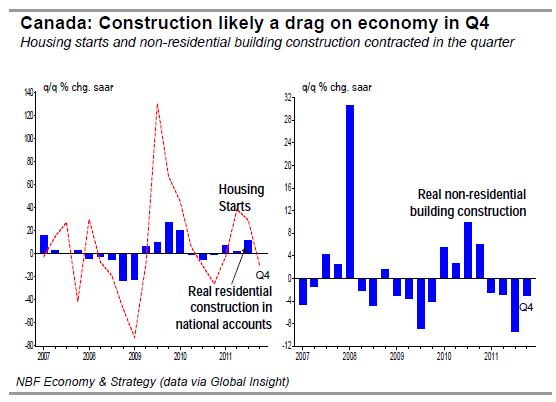

While the Quebec employment slump is puzzling, part of it can be attributed to a softening in the building construction industry (a big employer in the province). Building construction was indeed a clear drag on overall Canadian growth in Q4. Non-residential building construction saw a fourth consecutive quarter of negative growth, while residential construction may have contracted for the first time since the end of 2010 if the national housing starts data are any guide. The oft-mentioned forthcoming Canadian housing slowdown may finally have arrived. That’s one factor which we argued, in our Winter Economic Outlook, will cause Canada to underperform the U.S. economy this year. A slow moving labour market coupled with some consumer deleveraging will work as to offset the benefits of low interest rates on housing.

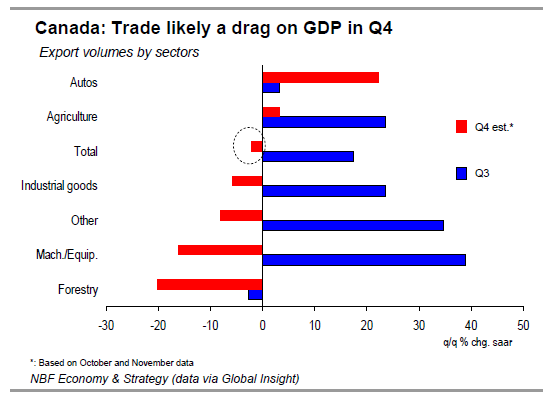

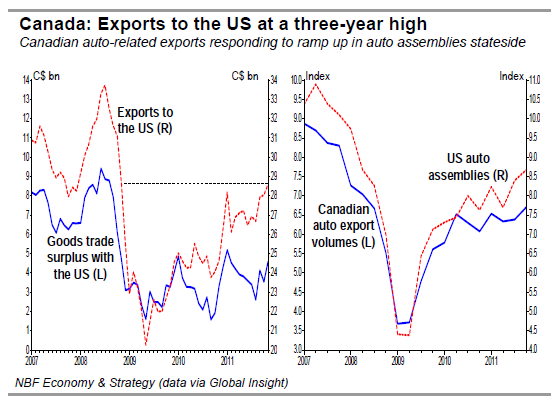

In light of the expected moderation in domestic demand, trade will take centre stage. It’s true that trade was likely a drag in the last quarter of 2011, as surging auto exports were more than offset by declines elsewhere. But 2012 may see trade turn into a net contributor, albeit a modest one. Our export revenues from the world’s largest economy reached a three-year high in November, helped in part by the ramp up in activity in the U.S. auto sector. Improving demand stateside should extend the uptrend in our exports through 2012.

Of course, the main threat to Canadian prosperity this year is a financial crisis à la 2008-09. With inflation well under wraps – annual core inflation is now below 2%, while the headline rate is at 2.3% - the Bank of Canada has more flexibility to act if necessary. But barring a Europe-led financial crisis, we continue to expect the BoC to resist rate cuts given the tighter Canadian output gap and Governor Carney’s repeated concerns about the ramp up in household debt.

- English (UK)

- English (India)

- English (Canada)

- English (Australia)

- English (South Africa)

- English (Philippines)

- English (Nigeria)

- Deutsch

- Español (España)

- Español (México)

- Français

- Italiano

- Nederlands

- Português (Portugal)

- Polski

- Português (Brasil)

- Русский

- Türkçe

- العربية

- Ελληνικά

- Svenska

- Suomi

- עברית

- 日本語

- 한국어

- 简体中文

- 繁體中文

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Bahasa Melayu

- ไทย

- Tiếng Việt

- हिंदी

World: Overall Resilience

Published 01/31/2012, 01:01 AM

Updated 05/14/2017, 06:45 AM

World: Overall Resilience

Latest comments

Loading next article…

Install Our App

Risk Disclosure: Trading in financial instruments and/or cryptocurrencies involves high risks including the risk of losing some, or all, of your investment amount, and may not be suitable for all investors. Prices of cryptocurrencies are extremely volatile and may be affected by external factors such as financial, regulatory or political events. Trading on margin increases the financial risks.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

© 2007-2025 - Fusion Media Limited. All Rights Reserved.