The euro zone remains the centre of attention. Fears for two of the heavyweights, Spain and Italy, are up a notch. To add to the worry, reports of September retail sales and industrial production suggest a euro zone already in recession. On the other hand, there has been encouraging news from both the U.S. and China. We think the global economy will continue to expand in the fourth quarter.

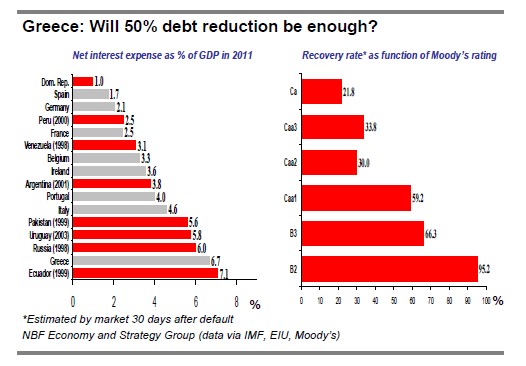

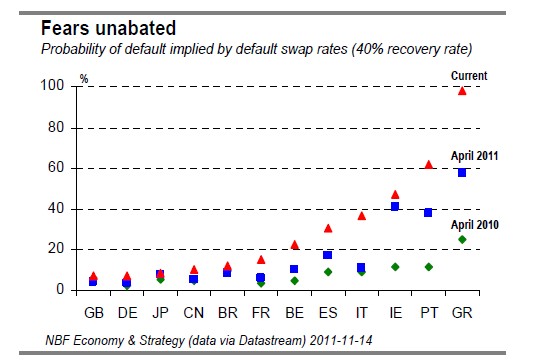

The workout plan for the European debt crisis brought only a few days’ respite. Among other provisions, the plan recognized Greece’s insolvency and proposed an orderly partial restructuring of its debt, in which Greece would have to repay only half of what it owes to the private sector. With this 50% reduction, the country’s debt-to-GDP ratio would fall to about 120% by 2020 – better than today’s 165%, but in our view still a very heavy burden. Assuming an interest rate of 5% (highly optimistic given the 7% that Italy recently had to pay to refinance), a debt of 120% of GDP would cost 6% of GDP to service. By way of comparison, seven of the last eight countries to default had debt service costs smaller than that. After Mr. Papandreou’s announcement that he would put that plan to a referendum, he resigned and left his place to a new coalition government that will finally move ahead with the reforms demanded for it.

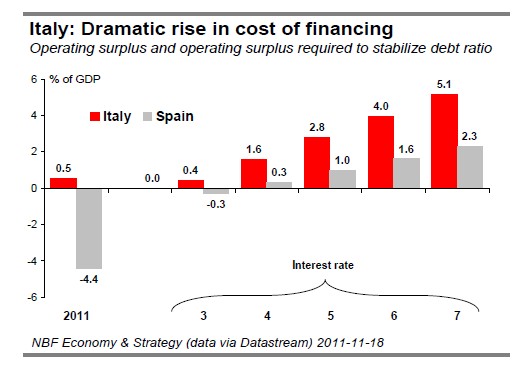

Spreads to German bond rates have widened for most euro countries in recent weeks. But the most troubling cases are those of two heavyweights, Italy and Spain. Not so long ago it was Spain that aroused more worry. Its debt, though still a relatively low 67% of GDP in 2011, was ballooning because of large government deficits. Today, investors are more worried about Italy, whose debt is 121% of its GDP and which has been slow to put in place structural reforms that would bring government spending growth into line with revenue growth over the coming years. The interest rate that Italy must pay to float its 10-year bonds recently topped 7%, the threshold at which other troubled euro countries have called for help. By our calculation, based on the IMF’s five-year growth forecast, Italy’s current debt and its operating surplus, a financing rate between 3% and 4% would be required to stabilize the country’s debt-to- GDP ratio. That’s approximately the rate Italy was paying a year ago. To stabilize its debt ratio while paying 7% interest, the country would have to run an operating surplus of 5.1% of GDP instead of the current 0.5%.

In other words, each refinancing at 7% would force it to introduce further austerity measures. Since Italy’s debt ratio is higher than Spain’s, the rise in financing rates exacerbates its problems much more. Italy’s debt is greater than that of Ireland, Greece, Spain and Portugal combined, making it a much greater systemic risk than other countries.

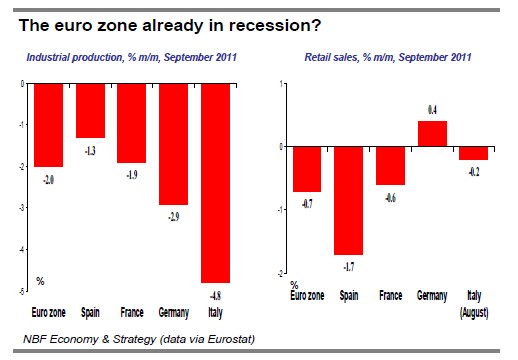

The odds of recession in the euro zone have been raised in recent months by the effect of the sovereign debt crisis on household and business confidence and by the austerity measures that have been launched in a number of countries simultaneously. Euro-zone industrial production fell 2% in September. In Italy, the worst performer, the decline was 4.9%. Germany, Europe’s manufacturing power, recorded a second straight month of decline. September retail sales were also disappointing – down 0.7% for the zone as a whole despite Germany’s 0.4% rise, which was disappointing after a 2.7% contraction in August.

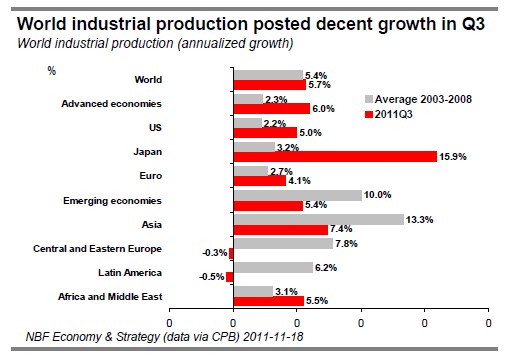

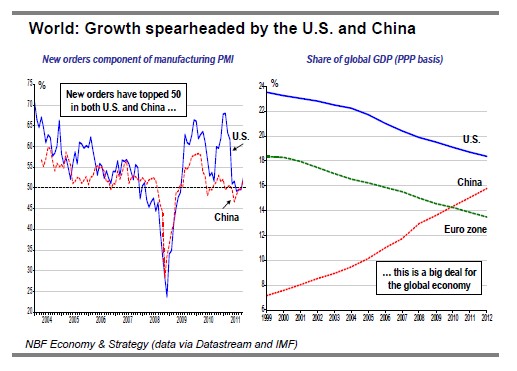

Data on world trade from the CPB were also disappointing for September, trade down 1% and industrial production decreasing 0.4%. But due to monthly data volatility, we are not overly concerned by this report. If you look at the quarter as a whole, industrial production was up 5.7% annualized, which is above the performance of the expansion from 2003 to 2008. This progression is only partly explained by strong growth in Japan (still in catch up mode due to the consequences of the tsunami) since both U.S. and Euro-zone also posted growth over their trends. Moreover, manufacturing sector in both U.S. and China should hold out in coming months. In both countries the new orders component of the manufacturing PMI index moved above 50 in October for the first time in seven months, auguring well for future production. The U.S. and China together account for about 35% of global GDP, compared to less than 14% for the euro zone.

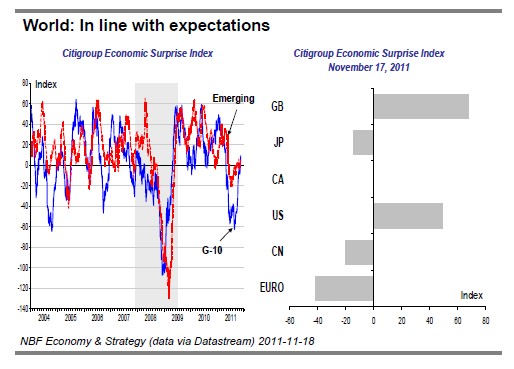

The economic surprise indexes of both the G-10 countries and emerging countries attest that economic indicators are now in line with consensus expectations. This is welcome news, since the consensus, even after revising down its outlook, sees global growth on the order of 3.7% in 2011 and 3.6% in 2012. The U.S. has surprised on the upside recently, as has the U.K.

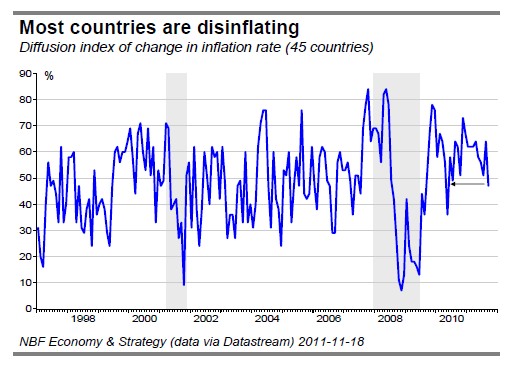

Some central banks have put their shoulders to the wheel in support of growth recently. The ECB and the Reserve Bank of Australia have lowered their policy rates. And since a majority of countries report 12-month inflation lower than a month earlier (a first in 14 months), other central banks may find room to make their monetary policy stance more accommodative.

In summary, if euro-zone sovereign debt does not tip the world into a credit crisis, the global economy will continue to expand in Q4 even without a contribution from Europe. While we revised down our growth forecast for the latter in 2012, we continue to see global growth over 3% next year.

U.S.: Accelerating growth

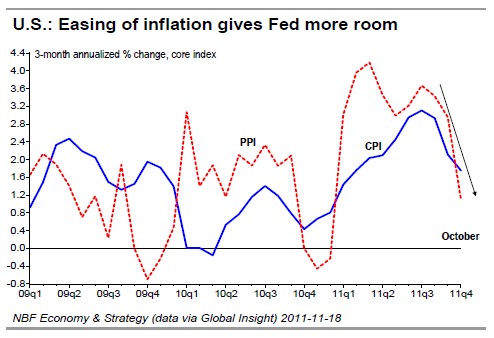

The U.S. not only managed to stay out of recession this year, but accelerated as the quarters went by. With October data in, Q4 is now tracking well over 2%, the best quarterly performance this year. So much so, that the Fed opted to do nothing new at its most recent meeting. Consumers and industry remain firm and the labour market is on a clear uptrend. That said, U.S. expansion next year is threatened by the risk of a European-triggered global financial crisis and by fiscal drag. As inflationary pressures fade, the Fed will have more room to deploy a third round of quantitative easing if the economy takes a sour turn.

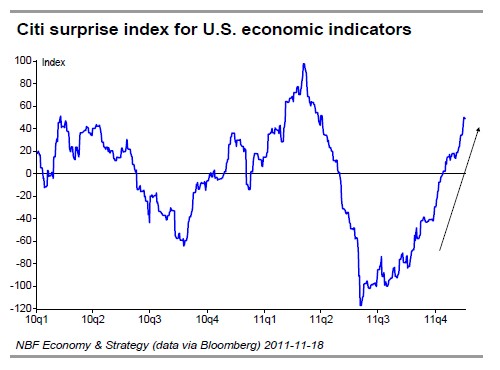

Recession? What recession? Just a few weeks ago analysts were clamouring about a likely U.S. downturn. But even taking into account the downward revision to Q3 GDP (to 2% annualized), the American economy accelerated in the second half of 2011 thanks to healthy exports and strong domestic demand. So much so, that it continues to grind out consensus-topping numbers taking the economic surprise index even further into positive territory.

Exports rose over 10% annualized in Q3, the ninth consecutive quarter of double digit growth. The cheap trade-weighted US dollar is no doubt helping here, but so is global demand which has remained resilient so far, despite the European debt crisis. The domestic economy has also surpassed expectations thanks to strong business investment and resilient consumption.

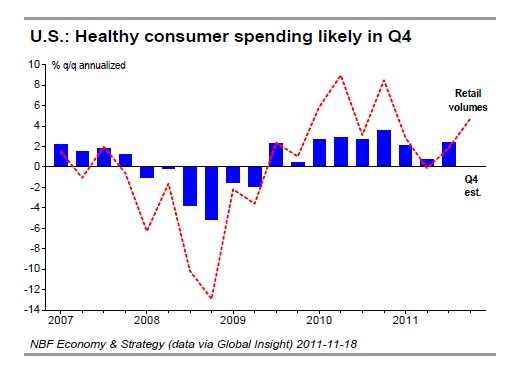

Consumer momentum carried through to Q4 as evidenced by strong October retail sales which expanded 0.5%. Highlighting the resilience of American consumers were the further increase in sales of discretionary items, +0.6% in the month following a 1.5% increase in September. Retail volumes are on track for annualized growth of 4.7% in the final quarter of the year even assuming a flat November and December.

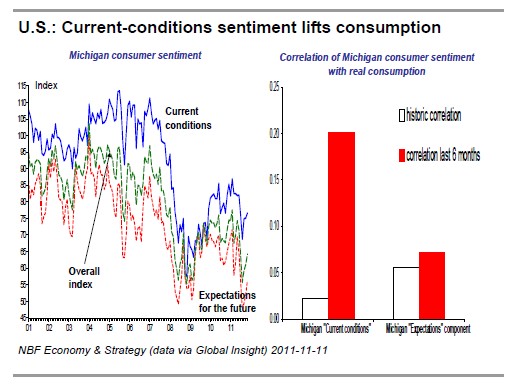

But sales growth has potential to accelerate further if the rising confidence, as depicted by the Michigan survey of consumer sentiment, is any guide. The survey shows Americans more upbeat about current conditions than about the future. In fact, in recent months, the correlation between changes in real consumption spending and changes in the Michigan’s index has been stronger for the “current conditions” index relative to the “expectations” index.

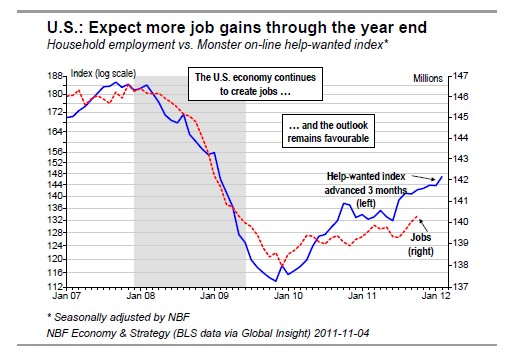

So while Americans may not be upbeat about the future, especially with uncertainty about US fiscal policy and Europe going into a recession, they’re still willing to spend if current conditions are good. And there is good news on that front. The economy is growing and the labour market is on a clear uptrend. With the downtrending initial jobless claims and the healthy “helpwanted” data (which tends to lead the household employment survey), expect further job creation ahead, something that should keep consumers upbeat and spending.

While consumers remained firm in Q4, so has industrial production. IP data for October showed a 0.7% monthly increase, causing capacity utilization to rise five ticks to 77.8%. Mining and manufacturing production continue to expand, with the latter helped by auto production which soared 3.1% in October. IP growth is now tracking 2.6% annualized in the final quarter of the year.

Even housing is surprising on the upside in the US. In October, housing starts reached 628K and the strong building permits in that month (653K) suggest some upside ahead for residential construction. No wonder that builders are getting back in the mood. November’s National Home Builders’ confidence index rose to 20, the highest since May of last year, and the second highest since April 2008. While we’re not anticipating the housing market to rebound sharply, we’re encouraged to see signs of it levelling off.

Indicators of consumption (retail sales) and industrial production in October show fourth-quarter GDP growth shaping up as the best of 2011 at well over 2%.

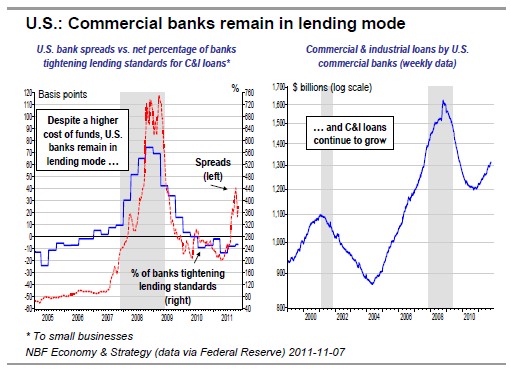

FOMC members continue to debate whether or not to deploy QE3 (i.e. unsterilized bond purchases). While easing inflationary pressures may give the Fed some room for that (CPI and PPI were both down in October), the improving economy makes that less necessary at this point. GDP growth clearly accelerated in the second half of the year. Moreover, credit seems to be flowing again in the U.S. economy, with commercial banks remaining in lending mode. The proportion of banks tightening lending standards is lower than just before the recession struck while commercial and industrial loans continue to expand. That said, QE3 may still be an option for the Fed next year, either if global financial markets freeze (i.e. if the eurozone and ECB fail to stop the rot there) or if the US fiscal drag turns out to be too brutal for a still-fragile US economy. For now, we’re keeping our 2012 growth forecasts unchanged at 2.2% although that’s conditional on the proposed payroll tax cuts being approved by Congress. The brunt of the impact of the Super Committee’s failure will be felt only in 2013, although it’s unclear if the resulting automatic cuts to spending will be allowed to stand by a new Congress after the 2012 Presidential elections.

Canada: A better second half

While Q3 GDP wasn’t yet available at this writing, it’s apparent from monthly data that Canada bounced back sharply in the third quarter following a disappointing Q2. The fourth quarter isn’t looking too bad either, particularly with the larger-than-expected U.S. rebound. The acceleration may have allowed Canada to top the BoC’s growth forecasts for the second half this year, although that’s unlikely to change the Bank’s monetary policy stance. The outlook for next year remains less buoyant given the expected headwinds from a slower moving global economy and the negative impacts of a strong Canadian dollar on trade.

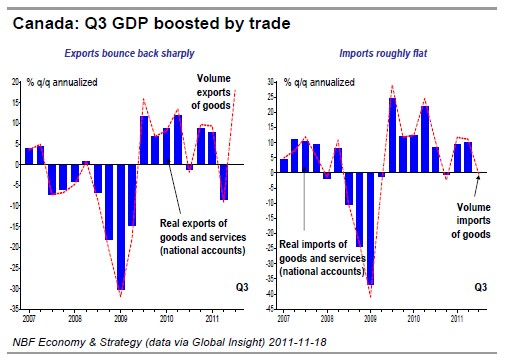

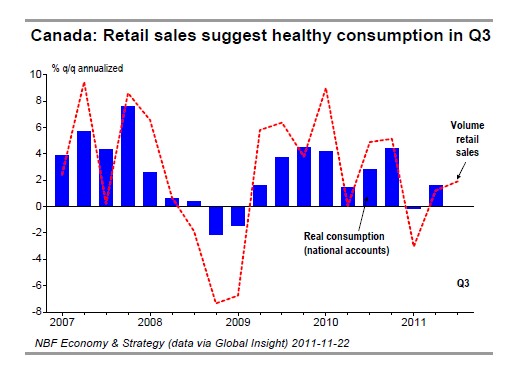

After being largely responsible for Q2’s GDP contraction, trade turned into a major contributor in the third quarter. Merchandise export volumes soared 18% in Q3, buoyed by sharp increases in exports of machinery and equipment, industrial goods and materials, agricultural products and a partial rebound in energy exports (the latter made up just about half of the lost Q2 exports). Real merchandise imports were roughly flat in the quarter as a strong increase in auto imports was offset by a drop in other categories, including the 11% annualized decline in imported volumes of machinery and equipment. While exports boosted Canadian GDP in Q3, the import data suggest some offset with a smaller contribution from inventories and softer domestic demand via declining business investment. That said, domestic demand likely got the support of consumers if retail data is any guide.

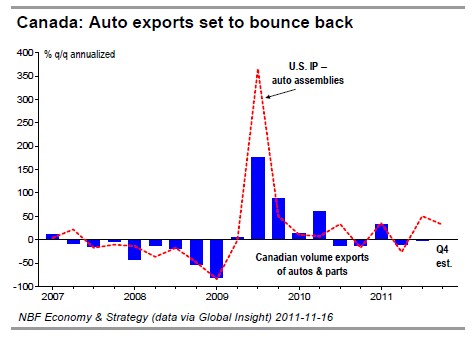

With manufacturing and retailing performing strongly in September, Canada is on track for growth of around 3% annualized in Q3, a notable rebound from the 0.4% contraction of Q2. The likely good handoff from September and the apparent pickup of the U.S. economy should also lift Q4 GDP. Early Q4 numbers stateside suggest good things for Canada. For instance, industrial production data for October showed U.S. auto assemblies expanding 6.5%, which puts US auto production on track for quarterly growth of 32% annualized. The tight correlation between US auto assemblies and Canadian auto exports suggest the latter will likely get a sizable boost in the final quarter of the year. Canadian exports for other consumer goods may also have done well if strong U.S. retail sales in October are any indication.

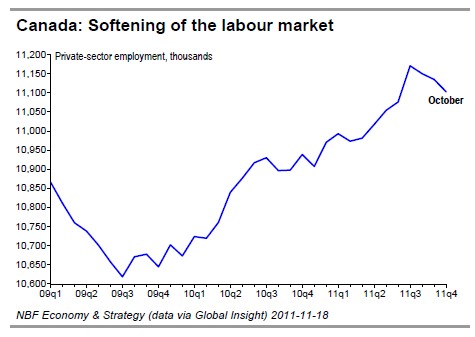

One concern, however, is a cooling labour market. After adding an average 28,000 jobs a month in the first seven months of the year, Canada has gained virtually no jobs over the last three months. The goods sector has been particularly hard hit over the August to October period, losing 85,000 jobs mostly in manufacturing and construction. The services sector has provided some offset, but not enough to prevent private-sector employment from contracting in October for the third month in a row – a first since the recession. While the trend is concerning, we do not see it as a bellwether of a new recession. Employers may be taking a more cautious stance after the hiring spree in Q2, a quarter that incidentally saw productivity come down significantly as GDP contracted despite the higher headcount. The Bank of Canada’s Business Outlook survey still showed that hiring plans were still relatively strong.

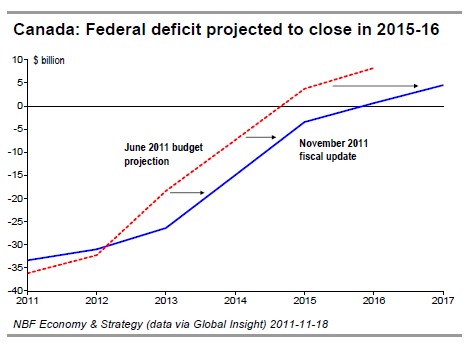

The outlook for next year isn’t particularly rosy given the expected headwinds from a slower moving global economy and a European recession. The bleaker long-term outlook has induced the federal government to lower its projections for GDP growth and hence for its budget balance. In its November fiscal update, the federal government pledged to close the budget deficit by 2015-16, a year later than originally planned. However, that’s contingent on finding $4 bn of cost savings. The Government will reduce the maximum potential increase in EI premiums for 2012 from 10 cents to 5 cents per $100 of insurable earnings. That measure will leave $600 million in the hands of Canadian workers and businesses in 2012. A welcome move, but not enough to change our growth forecast for next year.

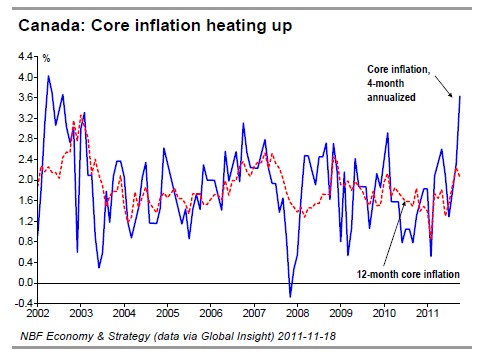

In our base case scenario, a global financial crisis is averted. If that’s the case, domestic demand is likely to remain strong in Canada and to continue feeding inflationary pressures. In October, both the annual inflation rates, headline (2.9%) and core (2.1%) remained above the BoC’s 2% target. More concerning is the ramp-up in core prices in recent months, with the highest four-month annualized increase since 2002. Clearly, price pressures aren’t easing as fast as the Bank of Canada had anticipated and under normal circumstances, it would be raising interest rates from the current extraordinarily low

levels. But the threat of a European-triggered global financial crisis is enough to keep the BoC on hold for now.