If it’s broke, fix it. The Federal Reserve is expected to embrace that rule when Jerome Powell, chairman of the central bank, speaks later today and outlines a new plan on inflation targeting.

“The expectations are pretty high to get something meaningful on Thursday,” predicts Tom Graff, head of fixed income at Brown Advisory. “This is probably a historic speech.”

By some accounts, Powell will deliver a policy plan that’s the book-end opposite of Paul Volcker’s focus when, as Fed chairman in 1979-1987, he pursued a hawkish inflation strategy that sharply raised interest rates.

“The main gist of the message is likely to point to a desire to overshoot inflation but to no specific policies for getting there,” advise Roberto Perli and Benson Durham of Cornerstone Macro in a research note to clients on Wednesday.

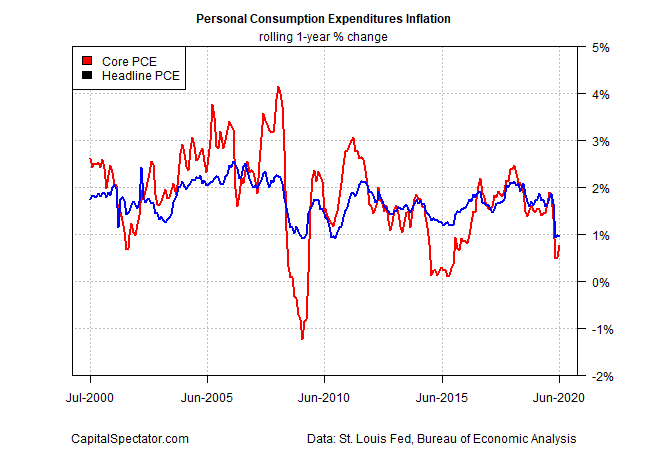

Measured by the Fed’s 2% inflation target, pricing pressure has certainly been low recently. Before the pandemic, the annual pace of personal consumption expenditures (PCE) inflation – the central bank’s preferred index for inflation – was running in the mid-1% range. But that moderately below-target pace has fallen sharply since the coronavirus crisis reordered the economy. Core PCE, for example, rose just 0.9% in June vs. the year-earlier level – close to a 60-year low.

Powell is widely expected to discuss what’s known as average inflation targeting (AIT). Barron’s summarizes AIT as a policy “to let the economy run hot whenever possible to offset all the times when prices rise too slowly. In practice, that means an inflation target of something closer to 2.25% when the economy is doing OK.”

Although the Fed will likely eschew radical changes, at least for now, a formal embrace of AIT would be a recognition that the currency policy isn’t working. In the grand scheme of managing the economy these days, this revision is likely to be a modest adjustment relative to recent history. Nonetheless, taking a more aggressive approach, even on the margins, is hardly trivial for the world’s most important central bank. A key question is how the markets – the Treasury market, in particular – reacts?

The bigger issue is what AIT means for the economy? “The Fed is in a position where they see the recovery is losing momentum at a time when the economy is in a deep hole, and that is worrisome,” says Diane Swonk, chief economist at auditing firm Grant Thornton.

AIT may not be a silver bullet, but it will help, say economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. Average inflation targeting, they write this month, is “a monetary policy framework that is well suited for the current environment.”

Explaining the need to reframe the policy focus, they advise that conventional monetary policy tools “face challenges in a low interest rate environment. While unconventional tools such as forward guidance and asset purchases are available to address these challenges, changes in the fundamental monetary policy framework may help in fulfilling the Federal Reserve’s mandate in prevailing economic conditions.”

Maybe, but skeptics are wondering how high a band will the Fed permit for overshooting its inflation target – and for how long? Ed Yardeni of Yardeni Research recently speculated that the “the Fed publicly would welcome inflation in a range of 2% up to 4% as a long overdue offset to inflation running below 2% for so long in the past.”

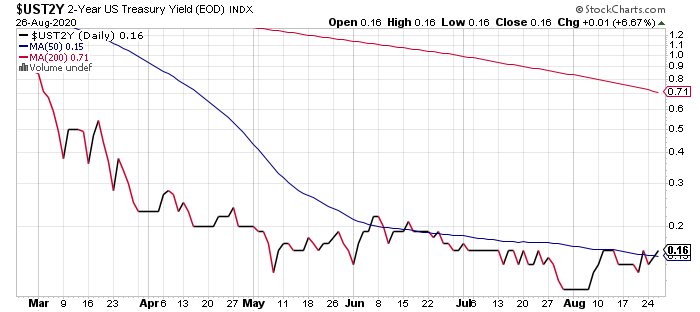

The crowd’s assessment, so far, is mostly a yawn. The 10-year Treasury yield, for example, has remained in a tight 0.5%-to-0.7% range since June. The 2-year yield, which is widely monitored as a benchmark for policy expectations, has also been flat-lining for several months, fluctuating between 0.1% and 0.2% recently.

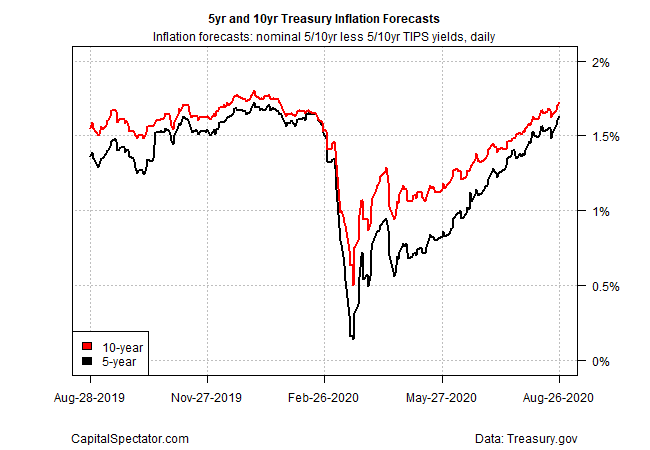

Note, however, that the Treasury market’s implied inflation forecast continues to rise from the pandemic’s low. The yield spread for the nominal less inflation-indexed 5-year maturities rose to 1.63% yesterday (Aug. 26). The current level marks a return to the pre-pandemic levels. The question is whether the bounce over the past several months will continue?

It’s unclear how a policy revision will affect markets and economic expectations, but it’s still remarkable that the Fed is planning to loosen it’s upside tolerance for inflation while the Fed funds target rate is close to zero and pricing pressure is weak.

“Since we’re already at zero, it means we’ll be at zero even longer and the central bank is going to be even more aggressive about trying to meet its inflation mandate,” observes Jon Hill, senior fixed income strategist at BMO “In the past they pre-emptively hiked to get ahead of inflation pressures. What they’ve shifted to is actually waiting until they get sustained inflation.”

Deciding whether this shift will be successful – or unleash unintended consequences – will take time. Assessing the odds, one analyst is managing expectations down.

Cornerstone Macro’s Robert Perli says the Fed is right to revise its policy, but AIT as currently conceived will fall short of what’s needed. “The Fed is putting up a valiant effort,” he says. “I think the odds that it will succeed are low.”