There may have been a time when the long view predominated among investors, but if it did it’s more likely to be a fable than an historical fact. We live in an age when far too many investors are necessarily familiar with the VIX index (an index of equity market volatility), and this makes the decidedly unsexy world of low volatility investments especially appealing. People want to beat the averages, and they often try and do so in a hurry. In fact, one of the most reliable ways to win at investing is to be content at winning slowly.

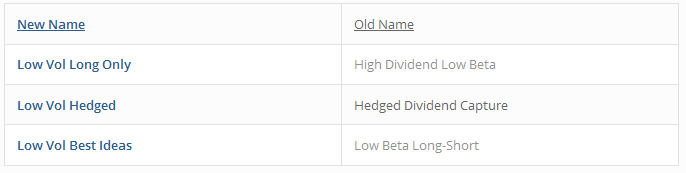

We’ve run low volatility strategies for many years. We used to call them “Low Beta” to indicate their connection with the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) and a flaw we seek to exploit, but few people outside of Finance care about Beta and so this month we renamed them to be more plainly descriptive. The amount of return you expect depends on the amount of risk you’re willing to take; low volatility stocks suggest low returns, and yet investors who follow such a strategy wind up turning some of the worst instincts of other investors to their advantage. The renamed strategies are listed below. Nothing else has changed other than their names.

In our opinion, the persistent relative outperformance of low volatility stocks relies on an interesting behavioral finance quirk. A substantial portion of actively managed equity portfolios are benchmarked against an equity index, ranging from large separately managed institutional accounts to retail-focused mutual funds. Because the investors are human, they tend to focus most closely on the relative performance of their chosen manager when returns are positive; when returns are negative they’re more concerned with the magnitude of the losses rather than whether they look good compared with a benchmark. Just think back to your own experience of evaluating positive and negative investment results to see if this reflects your own biases. We ought to value beating the benchmark by 2% in any year, but it turns out to be more valuable when returns are positive.

Active managers on average respond to this by structuring portfolios that are more likely to outperform a rising market. This is most easily done by investing in stocks that have higher beta (or volatility) than the market because they will probably go up faster. Their proclivity to fall faster hurts the manager less, since assets are best raised in a rising market. Therefore, equity managers who are not personally invested alongside their clients have an incentive to run portfolios that are more risky than the market. An alternative interpretation is that investors inadvertently favor such managers, but in any event it’s why low volatility stocks outperform. Although low volatility stocks are widely owned, they’re not widely owned by active managers because they don’t rise enough in a bull market.

This is a form of principal-agent risk, and the most effective alignment of interests is to ensure that your chosen active manager is substantially invested alongside the client. This is what we practice at SL Advisors, and in 2015 low volatility exposure provided a welcome distraction from the turmoil of MLPs.

Some pundits regularly lament the increasingly short-term nature of today’s investors. John Kay’s recent book Other People’s Money; The Real Business of Finance is a fascinating read for those who fret that today’s capital markets are insufficiently dedicated to trading rather than their more appropriate purpose of efficiently channeling savings to those businesses that can deploy capital in attractive ways. I am increasingly in that camp. The media, and most especially broadcast media, meets a very real need of their viewers to figure out where the market’s going today. It should be a misplaced need if you’re investing for the long run but today’s extraordinarily cheap access to public equity markets is wonderful if not wholly beneficial. The narrow difference between a day trader in stocks and one who spends his days betting on sports renders both little more than punters managing their shrinking capital.

The case that the short term outlook rules isn’t limited to perusing the media. Some of today’s investment products provide additional evidence. Leveraged ETFs are not intended to be used as part of any long term investment strategy and their prospectus plainly says so. Their successful existence illustrates the demand for cheap ways to bet on the market’s direction. Consenting adults are generally free to engage in any behavior they wish as long as it doesn’t hurt anybody else. Since such investments eventually have to go to zero (see “Compounding” below), the facilitation of self-harm to the buyers of one’s products surely puts the seller in the company of casino owners if not worse.

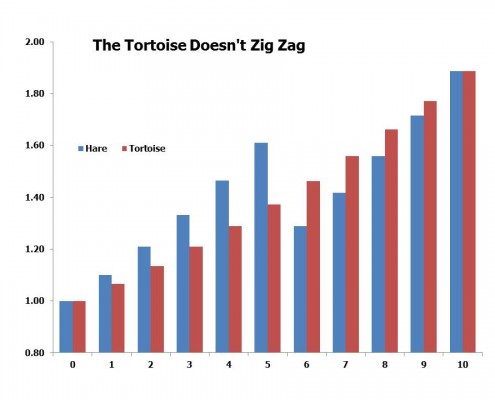

Compounding returns has long been a reliable way to build wealth, but it’s important to make it work for you. Most readers will be aware that a 10% drop in a security requires an 11% jump to get back to even. Lose half your value and prices then need to double. This means that a security that is up 2.00% on half of trading days and -1.96% on the other half will remain stubbornly at your purchase price in spite of the up days being bigger than the down days. However, obtaining such exposure through a 2X Leveraged ETF, which has to rebalance its leverage every day, would have you lose 10% in the course of a year. Maintaining constant leverage causes you to buy more of the asset after it’s risen, and sell more after it’s fallen, a self-destructive course of action. In the stylized chart of two growing companies, Hare and Tortoise (Source: SL Advisors), Hare grows earnings at 10% annually with one stumble when they drop 20%. Tortoise grows at 6.55% every year, thereby equaling Hare’s 10 year compound growth rate. They reach the same place, but you’d rather own Tortoise for the less stressful ride even though their visible growth rate is only two thirds of Hare. The power of compounding works best with low volatility.

Closed end funds, perhaps most spectacularly including those focused on Master Limited Partnerships, employ leverage. As bad as the Alerian Index was in 2015 at -32.6%, it was possible to do far worse. A Kayne Anderson fund (N:KYN) lost 51% in part because it was forced to reduce leverage following market drops, as noted in last month’s newsletter. Two leveraged MLP-linked exchange traded notes (ETNs) issued by UBS did even worse, as briefly noted at the end of a recent blog.

This letter began by expounding on the beauty of low volatility before moving on to the perils of leverage. If it’s not already clear, they are connected. Positive returns that don’t vary that much will often get you to a better place than those that fluctuate widely. Compounding works better with low volatility. It’s an area of investing where the low volatility, boring tortoise beats the volatile hare. If Aesop was a client of SL Advisors today, he would be in our Low Vol Strategy.