The entire financial system revolves around credit. At the heart of this system lies the ability of corporations and consumers to access credit, which is largely driven by the economic cycle and the willingness of commercial banks to lend and supply credit. This in turn drives credit spreads, asset returns and volatility.

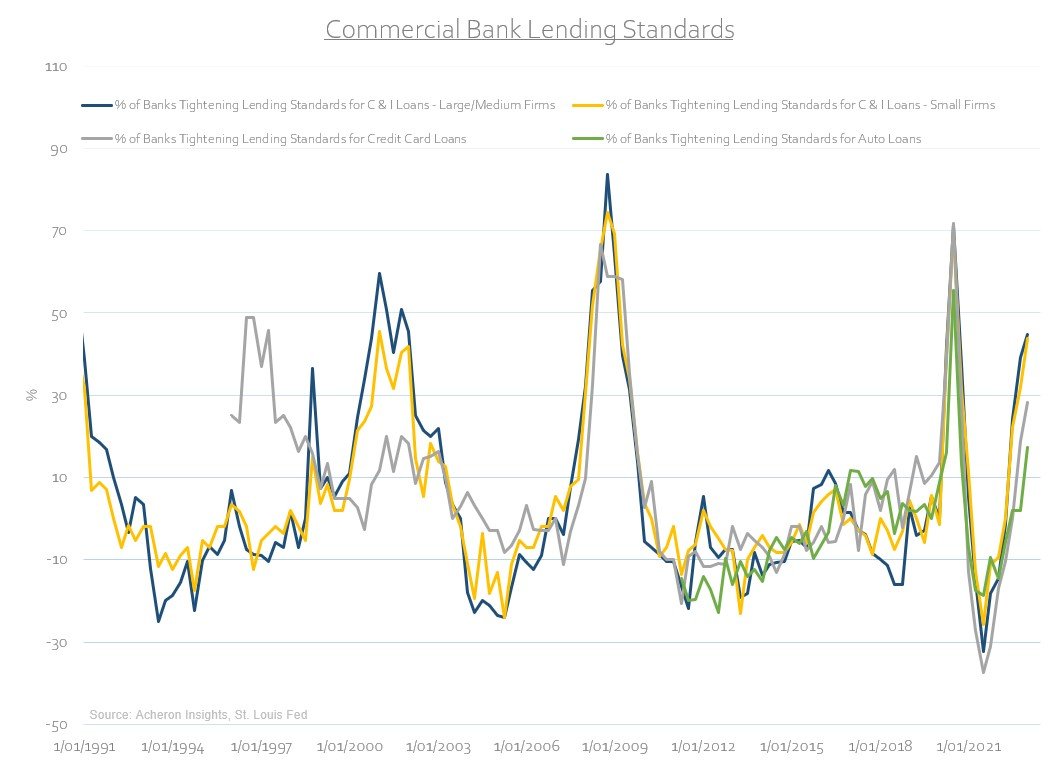

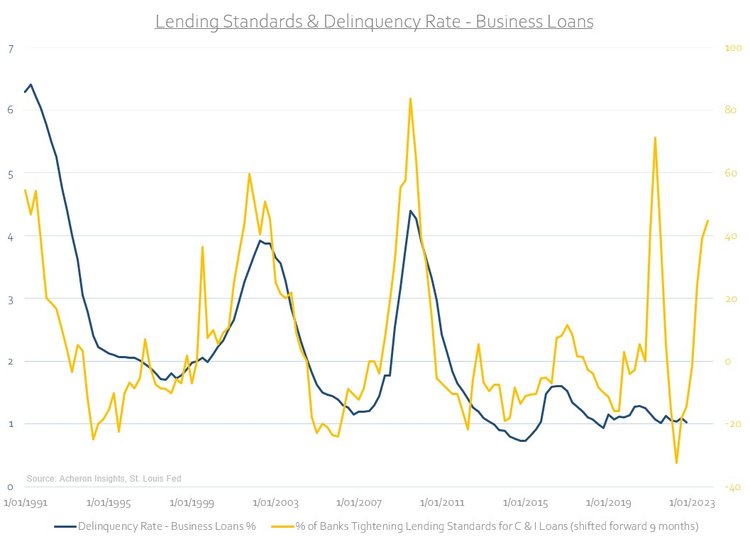

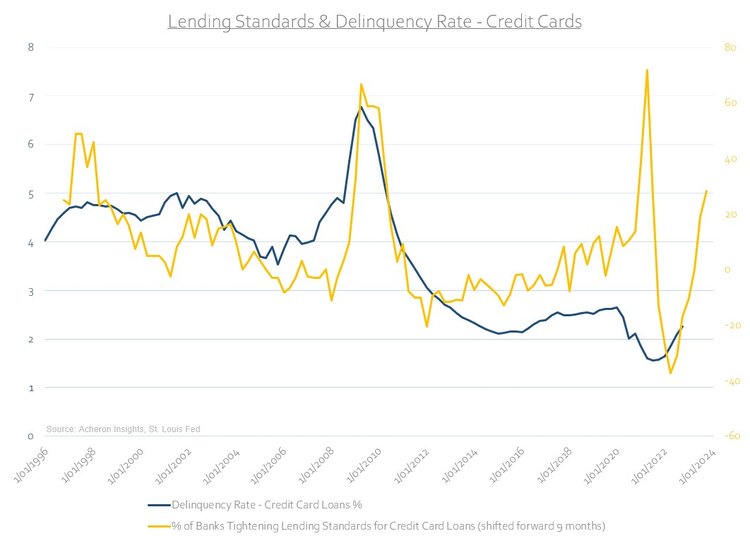

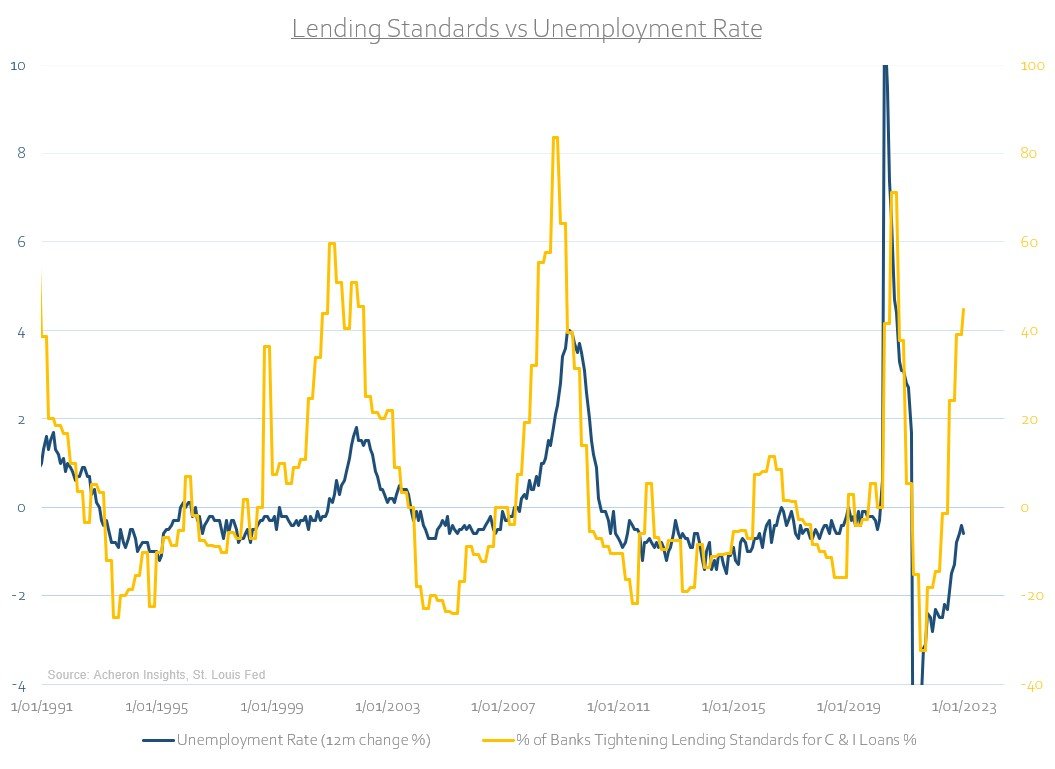

As the business cycle continues to trend lower, the latest Fed loan officer survey highlighted how restrictive commercial banks’ lending practices are becoming, with credit availability across the board reaching the tightest levels since the COVID-19 recession. This is true of commercial and industrial loans to corporations, credit card loans to consumers, as well as auto loans. All are at levels seen only during recession.

When credit conditions are loose and corporations can easily borrow, credit spreads are low as the risk of default reduces. This usually corresponds to periods of accelerating economic growth and abundant liquidity as corporations are overly optimistic and risk-seeking.

However, as the business and liquidity cycles decelerate and monetary policy conditions tighten, credit availability falls as banks are less willing to lend. For corporations and consumers who have overextended themselves with debt to spend and invest beyond their means, this is particular troublesome.

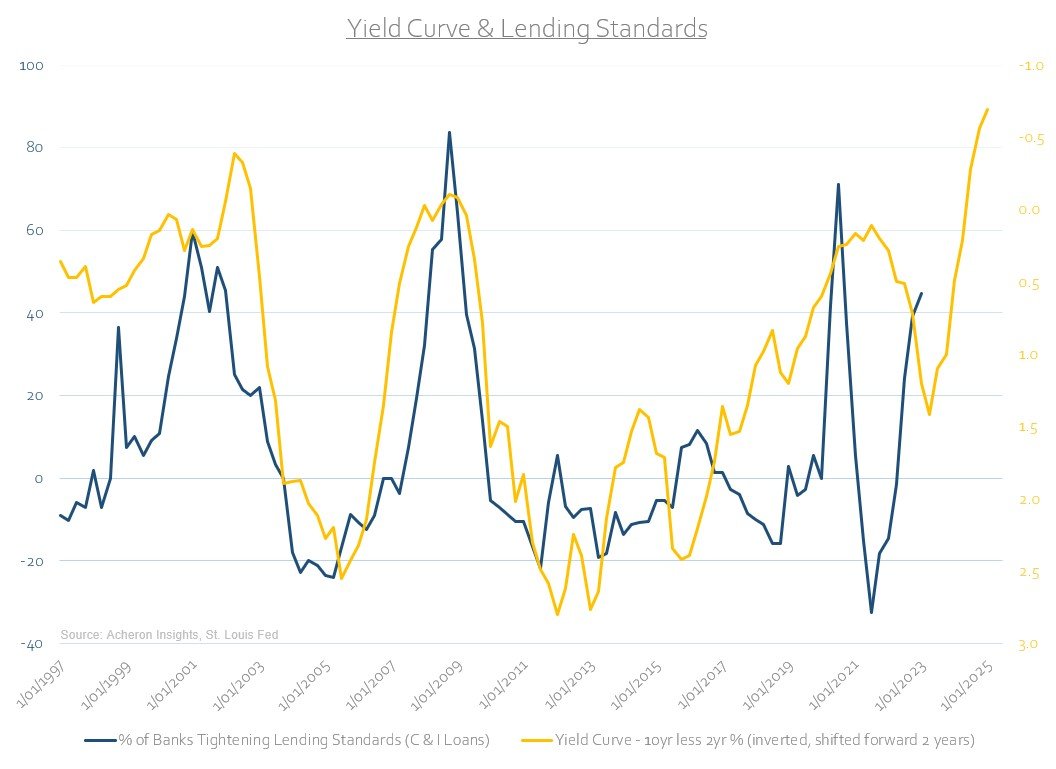

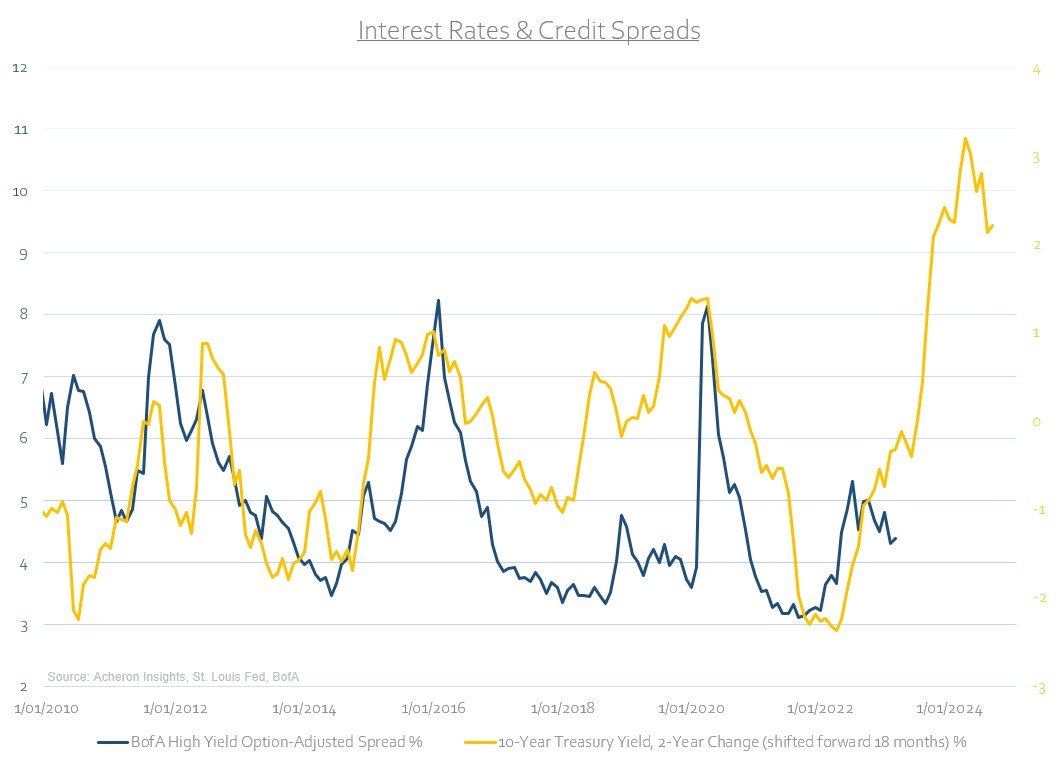

One of the most reliable leading indicators of credit availability is the yield curve. As the curve inverts, bank margins are squeezed and thus their incentive to lend fall. As such, the percentage of banks who are tightening lending standards tends to increase.

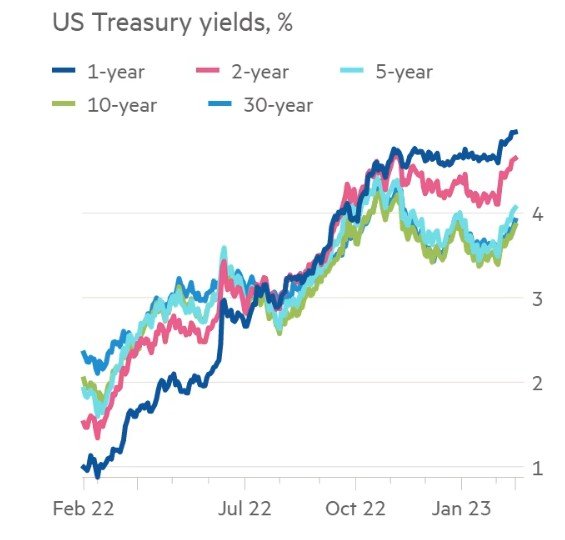

Banks profit from the spread of an upward sloping yield curve as they borrow on the short-end of the curve and lend at the long end. This spread evaporates when the yield curve inverts. As we know, all iterations of the yield curve are inverted and have been for some time, so this tightening of lending standards was to be expected (though appears yet to be priced in, as we will discuss below).

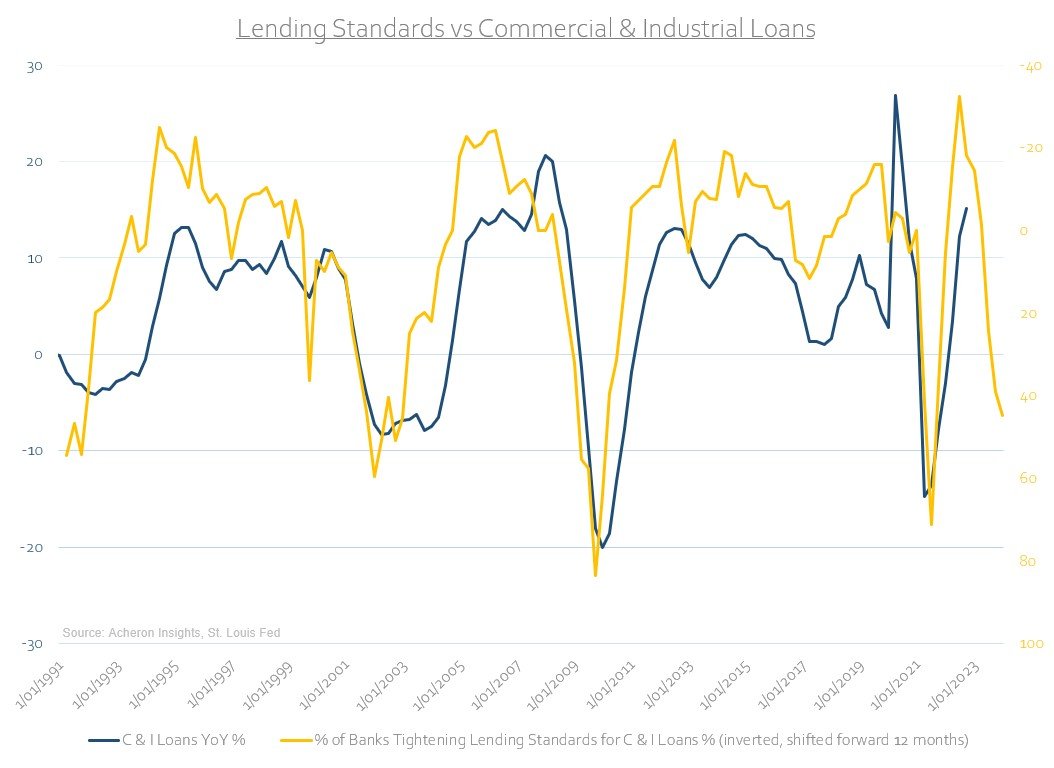

When lending standards tighten the ability for corporations and consumers to access credit is severely hindered. This is why we see loan growth follow lending standards, which I have proxied below via commercial and industrial loans, but the relationship is true most types of credit. Indeed, 2023 should therefore see loan growth roll over.

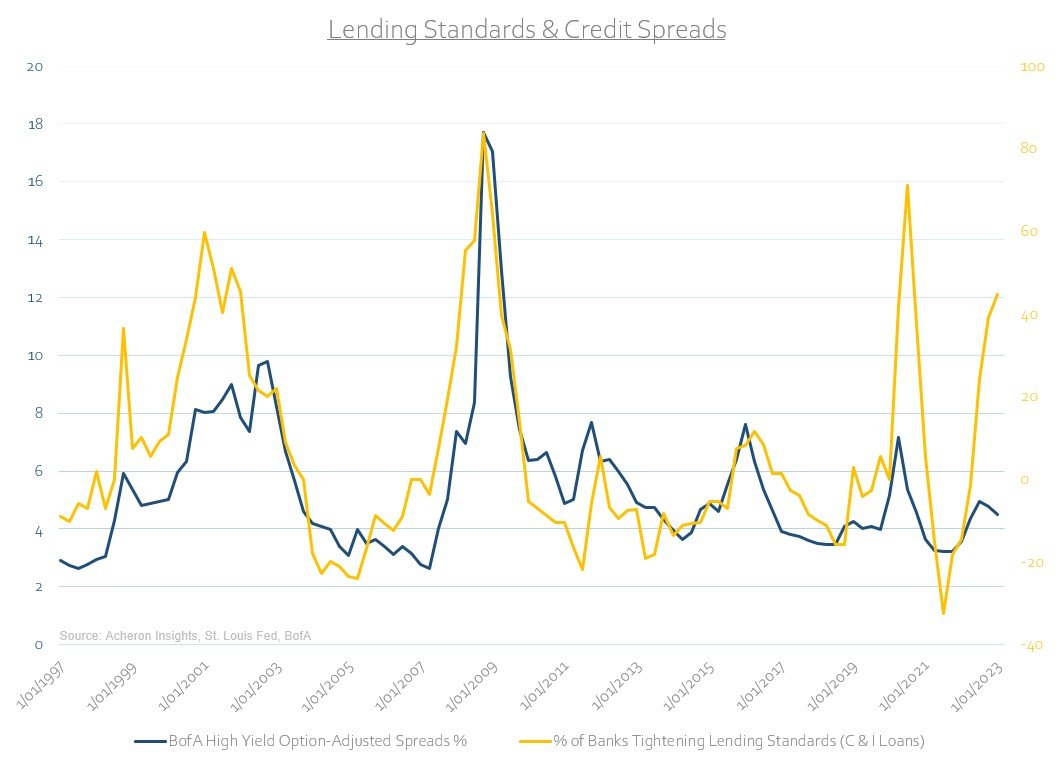

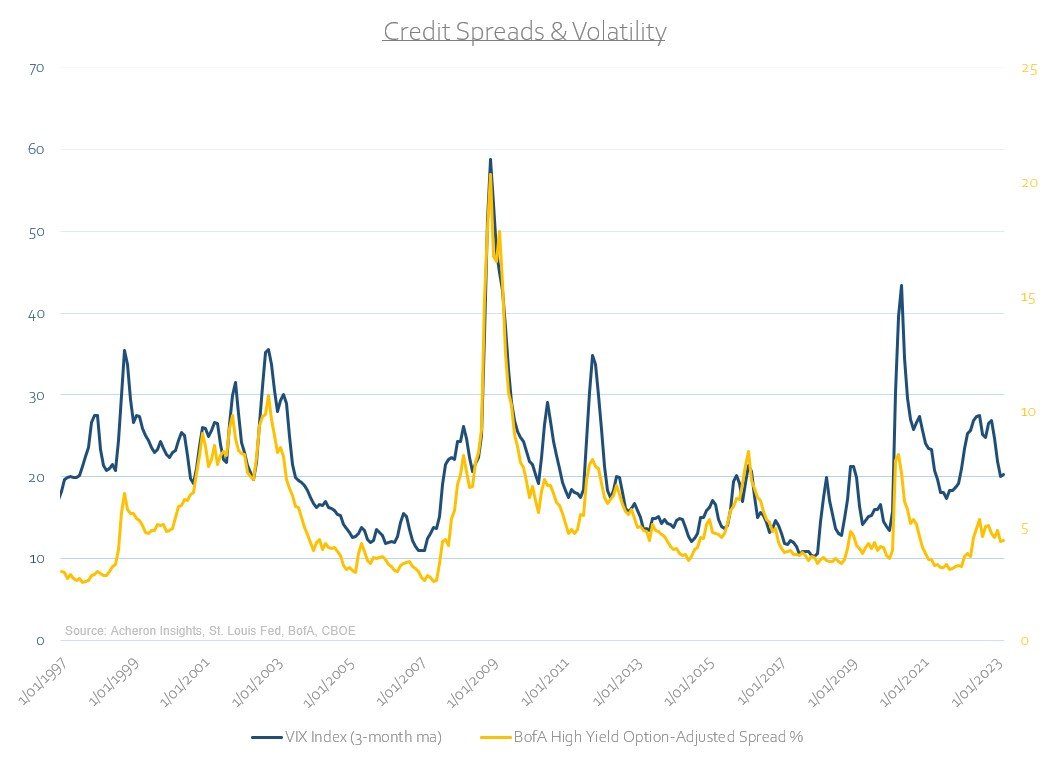

All told, this dynamic eventually finds its way into higher credit spreads, particularly for those of a lower credit rating. A reduction in the availability of credit leads to increased financial stress for overleveraged companies who cannot access credit when they need it most.

No soft-landing in sight

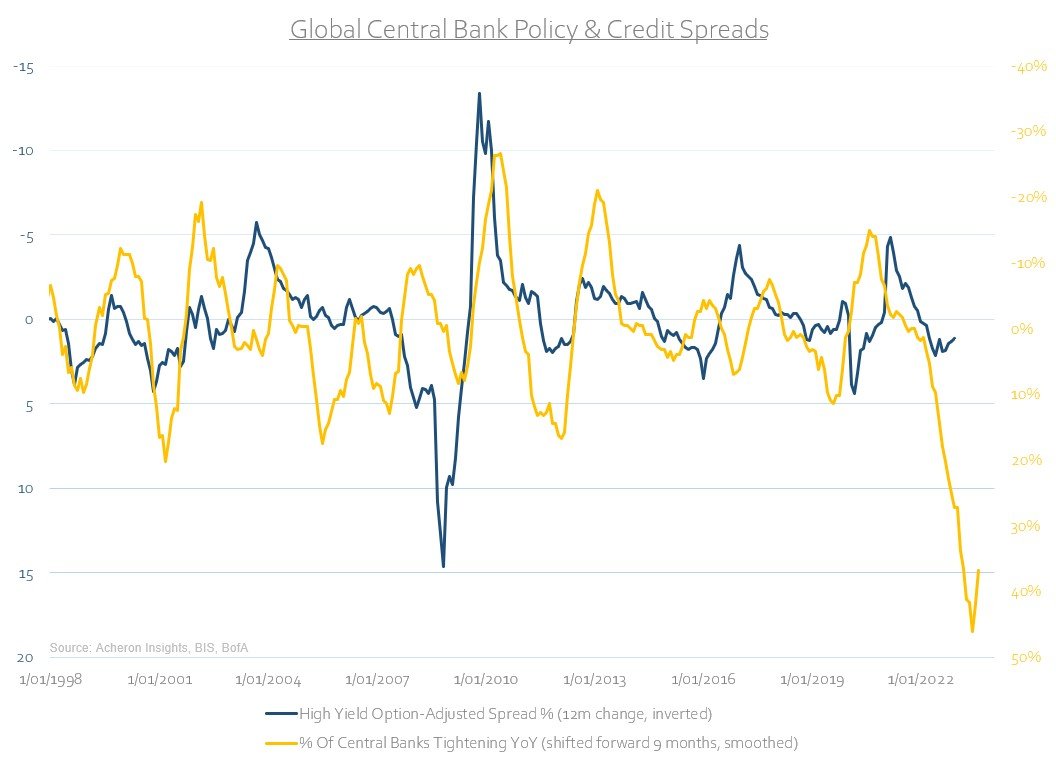

None of this bodes well for the soft-landing narrative. The leading indicators of the credit cycle continue to suggest higher credit spreads and are likely in the months ahead. In addition to tighter lending standards driving credit spreads higher, higher interest rates do the same.

As do tighter central bank policy conditions.

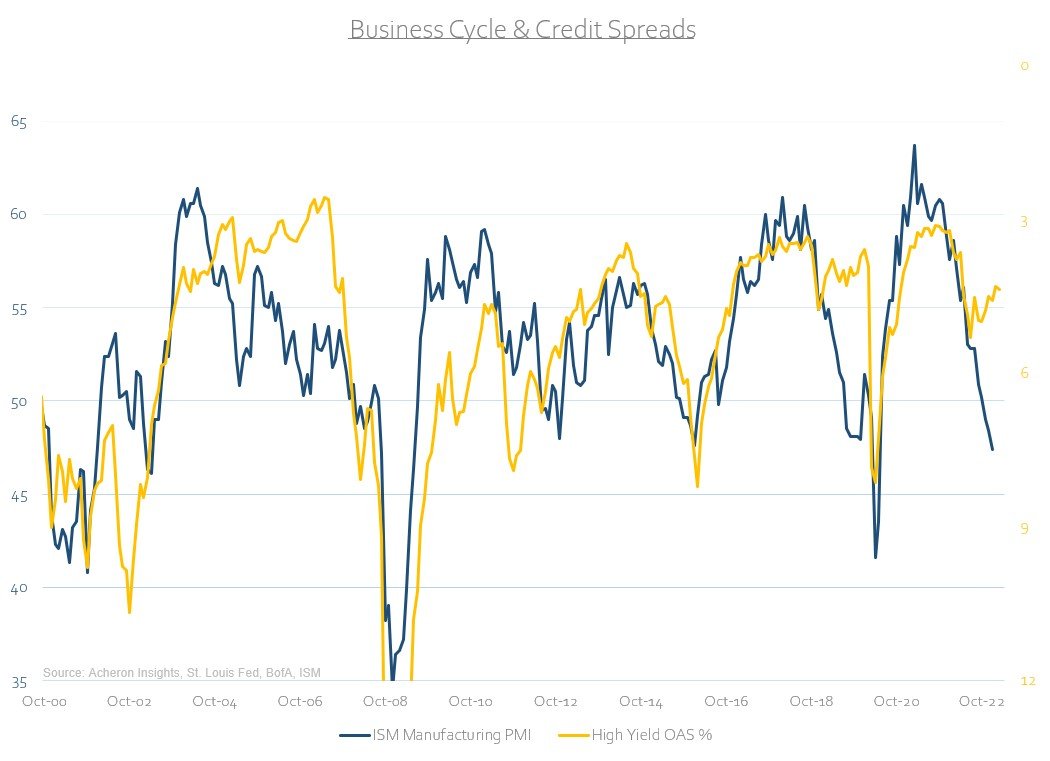

As it stands, the pricing of the credit market is not reflective of this outlook for the credit cycle. As we can see below, BofA’s high yield OAS is pricing a manufacturing PMI of above 50, indicative of a growing economy.

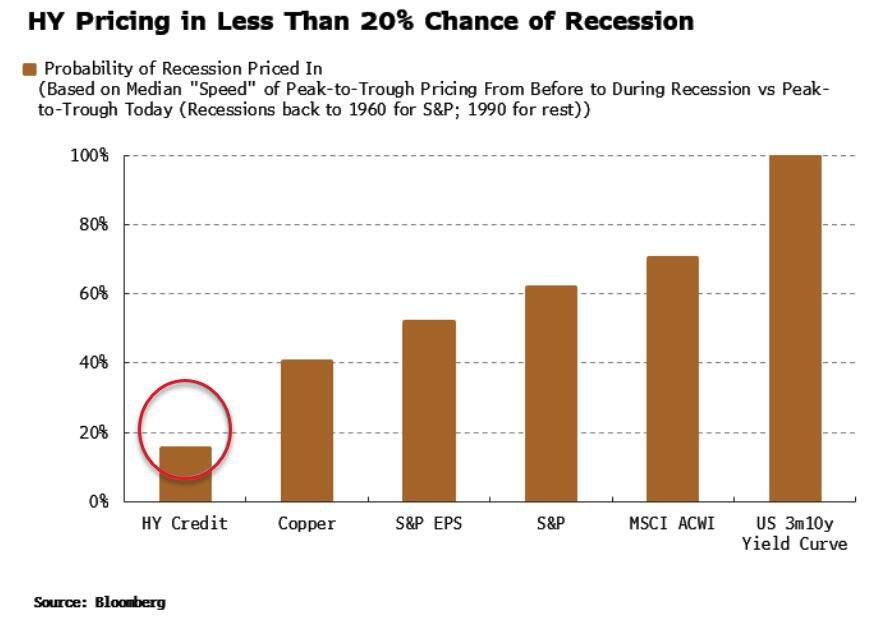

Indeed, as flagged recently via ZeroHedge, Bloomberg’s Simon White noted high-yield credit is pricing only a 20% chance of recession. Considering the outlook for the credit cycle highlighted herein along with the outlook for the business cycle itself, there appears to be a significant level of mispricing at present. For whatever reason, the credit market is betting on a soft landing.

Source: Simon White - Bloomberg via Zerohedge

This will not end well

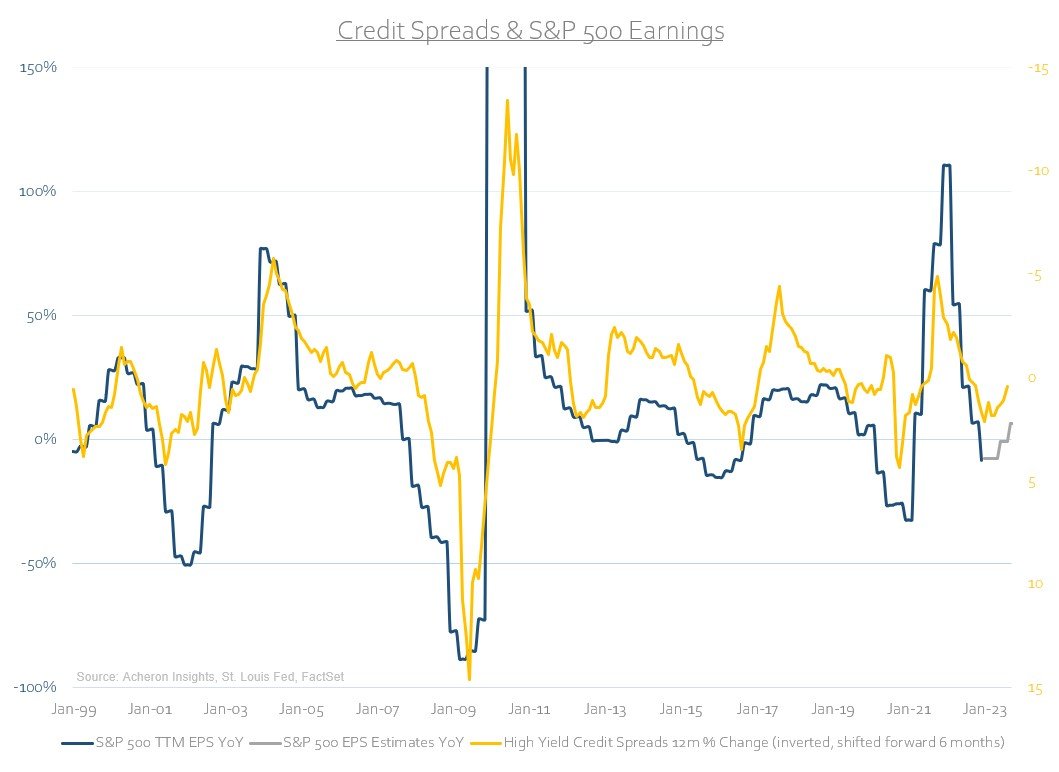

With the deterioration of the credit cycle looming, the unfortunate consequences will be pain for both financial markets and the real economy. Again, as credit spreads rise and bank lending standards tighten, access to credit becomes increasingly difficult for both corporations and individuals. This in turn puts great strain on corporate balance sheets and ultimately, corporate profitability. Credit spreads themselves tend to lead corporate earnings by around six months, so, while we may see corporate earnings hold up relatively well for the first half of 2023 in-line with EPS estimates, we know this is only temporary.

As higher spreads eventually find their way into earnings, they will in-turn lead to increased delinquency rates for both consumers and corporations as the burden of higher borrowing costs impacts those who are most vulnerable.

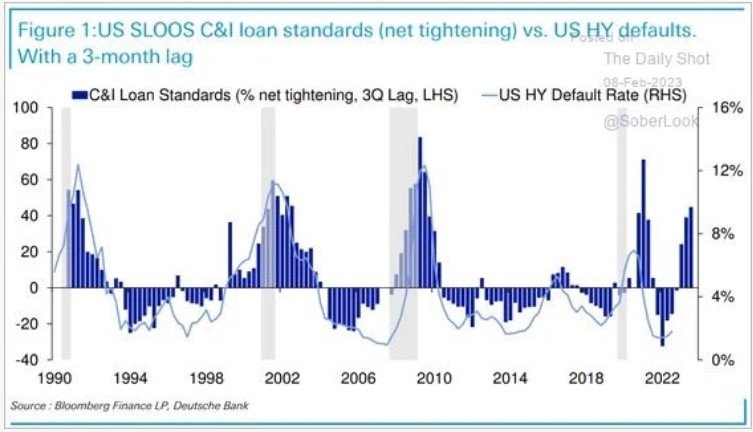

And thus, this ultimately will lead to increased defaults and bankruptcies.

Source: @SoberLook

And eventually, higher unemployment as firm’s lay off workers and these effects ripple through the real economy.

None of this bodes well for the stock market. As I have detailed in the past, the credit cycle is one of the best leading indicators of volatility. As credit spreads rise, volatility ensures.

Unsurprisingly, bank stocks are particularly vulnerable to this dynamic, at least on a relative basis.

Source: Ian Harnett - Absolute Strategy Research

There is simply no need to take credit risk

With short-dated Treasury yields at their current levels, there is simply no need to take meaningful amounts of credit risk at present. This can be argued of duration risk as well. The FT’s Robert Armstrong highlighted this point recently in excellent fashion, “Investors, in effect, have to pay to take duration risk. Why would you do anything other than own short bonds, and just keep rolling them over? You can always add duration risk later, when the Fed hiking cycle is over. Yes, you might think that 4-ish percent on long Treasuries is going to look mighty good when we fall into a recession, or you might just think 4 per cent is the cyclical top regardless. But those are bets. The 5 percent one-year Treasury is basically just money in your pocket.”

Indeed, extending this point to the matter at hand, Armstrong notes “Since the end of September, the amount investors get paid for taking credit risk has fallen dramatically. A-rated bonds (lowest rung of investment grade), now give you about a percentage point of extra yield over Treasuries, 40bp less than five months ago. On B-rated bonds (mid-junk), the reward for credit risk has fallen by 1.3 percentage points. When a large chunk of your yield is coming from the risk-free Treasury rate, why pile on credit risk? As Jim Sarni of Payden & Rygel put it to me (speaking of the short end of the curve), it’s not smart to go down in credit quality when the risk-free rate is 80 per cent of the total return.”

Source: Unhedged - Financial Times

From a macro perspective, I find it hard to argue with this analysis. Now is not the time to wander too far down the risk curve, and credit is no exception.