David Cameron has billed it as a ‘once in a generation’ decision for Britons and claims the UK will be irreparably damaged if it leaves the EU. However, in the event that the “Out” campaign reigns victorious, will the UK really slip into economic ruination? Furthermore, will a departure from the EU even have a significant impact on the UK?

Whilst a cursory glance at the media would have one believe leaving the Eurozone would cripple the UK, beneath the surface there may be a more sober prediction available. Ultimately, Britain will either escape from EU membership relatively unscathed or it could actually thrive once unshackled from its European neighbours.

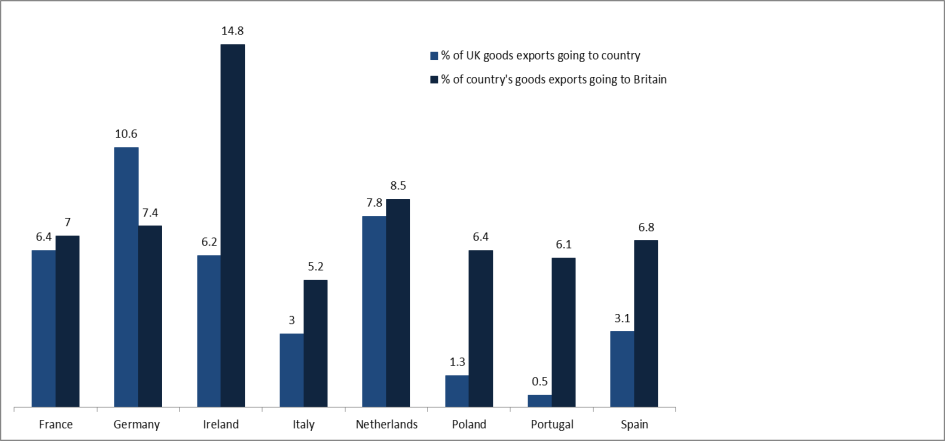

One of the key arguments circulated in opposition to the Brexit is the relative dependence that the UK has with the European Single Market. Official figures demonstrate that around 50% of all UK exports are destined for the EU. Conversely, only 18% of the total EU exports are destined to reach the UK.

As a result, some would argue that the UK would be poorly positioned to negotiate a free trade agreement with the EU after a Brexit. In the absence of such an agreement, exporting to its largest market would become more expensive and this could hinder the already sluggish UK economic growth. However, this only tells half the story as, in fact, the major economies of the EU are more dependent on the UK than the other way around.

As shown in the above graphic, bilateral trade between the largest economies in the EU and the UK generally shows that Britain is the more important trade partner. Consequently, Britain would actually be in a strong position to negotiate new trade agreements with the EU after a Brexit. As a result of this, UK exporters are barely at risk of losing access to the single market in the event of an out vote. Furthermore, without being shackled to the EU, Britain can pursue trade agreements with other countries not currently on the Union’s agenda.

Moreover, focusing British trade policy away from Europe represents a more robust strategy for long term growth. Considering that export demand growth is higher in countries from outside the EU, being free to negotiate trade agreements independently will benefit Britain extensively. Whilst the loss of collective bargaining power offered by EU membership will make some agreements harder to achieve, the ability to have greater independence in its trade policy will allow the UK to capitalize on the growth in demand from developing economies.

Specifically, comparing import growth in the Eurozone and India between 2007 and today demonstrates a clear advantage in pivoting away from the EU. In this period, import growth for the Eurozone as a whole grew around 40%2. In contrast, India saw its demand for imports more than double over the same period of time.

Despite the overall negligible long-term impact the Brexit is likely to have on the UK, one area which may be disproportionately affected by leaving the union will be the financial services Industry. Presently, EU membership allows the “passporting” of financial services to Europe by UK based firms. Obviously, this confers a huge advantage to any firms based in Britain as they can both make use of the financial industry cluster based in London and still have access to the EU single market.

It is argued that loss of passporting rights would erode the longstanding pre-eminence of Britain as a financial hub. However, the efficacy gains afforded to financial firms based in London likely outweigh the potential costs of losing passporting rights. Moreover, any trade agreements struck after a Brexit are more than likely to include some concessions to the powerful financial industry.

Another overblown fear being generated by the Brexit is the potential damage that the departure would do to Foreign Direct Investment into the country. Figures are bandied about which show that currently upwards of 45% of FDI into Britain originates in the EU.

Whilst it is true that a large degree of investment presently comes from the European bloc, the relevance of EU FDI is reducing in the UK’s future. Specifically, European direct investment into the United Kingdom has been decreasing steadily over the past few years.

Conversely, investment from non-EU members has been increasing as time progresses. Therefore, if EU FDI attrition is already occurring while still in the Union, one can hardly argue that staying will cause EU FDI to increase.

One explanation as to why non-EU countries are increasing FDI into the UK could be because these countries are using the UK as a gateway into the European single market. Assuming this is the case, the fear then arises that in leaving the EU these FDI flows would dry up. However, as discussed earlier, there is likely to be very little disruption in UK businesses access to the single market.

Consequently, capital is likely to continue to flow into the UK after a departure from the EU. This is because the costs of multinational companies relocating UK offices to Europe would likely outweigh the slight inconveniences of dealing with tariffs. Additionally, if the UK is free to strengthen ties with non-EU members, the degree of FDI it enjoys could actually increase.

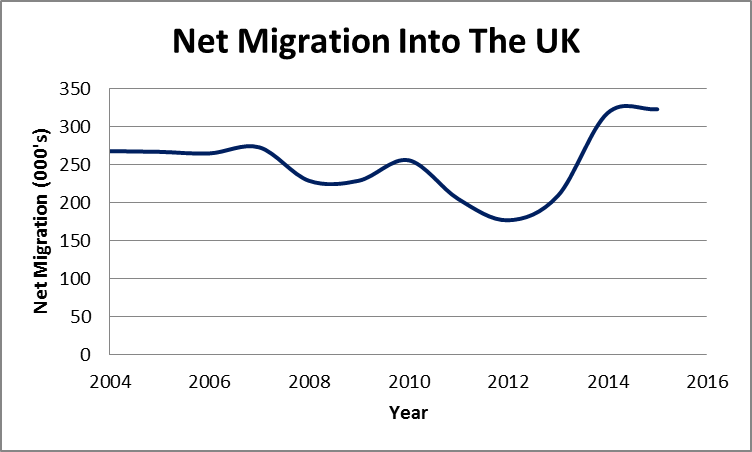

Immigration is another area where severing ties with the EU could be of great benefit to the United Kingdom. Under current arrangements, the UK must allow migration of EU citizens into Britain and vice versa. Consequently, it will come as little surprise that almost half of immigrants into the United Kingdom are EU citizens.

Immigration plays a vital role in supplying additional labour into the British economy, granting the UK access to labour and skills that it might otherwise be short off. However, the current net effect of immigration tends to lower the average wages in Britain which stifles incentives for high skilled workers to remain in the UK.

This phenomenon is often colloquially referred to as a “brain drain” and describes how high skill workers are prompted to leave a country as average wages decrease. A recent study by the Bank of England confirms the effect that migration has had on lowering wages in the UK. Furthermore, average wages in Britain have been falling for some time whilst immigration into the UK increased by just over 20% since 2004.

Whilst lowering average wages across the British economy is one negative of increased immigration into the UK, the nature of those immigrating is another problem entirely. Presently, the Migration Advisory committee estimates that almost half of the new immigrant stock from the past 10 years is classed as low skill. Consequently, there has been a deluge of labour into the low skilled labour market which has disproportionately and negatively impacted wages in industries reliant on these workers.

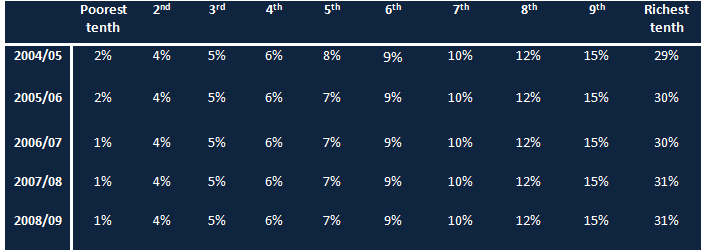

As a result of this, the income inequality between low and high skill workers is deepening dramatically. Looking at the UK Gini Coefficient, since 2004 the poorest 10% of Britons have reduced their net share of total UK income from 2% to 1%. Conversely, the richest 10% have increased their share from 29% to 31%8.

The reduction of income for poorer individuals is important as they typically consume a greater proportion of their total income than the richest 10% who are more likely to save. Reductions in consumption are the last thing that the sluggish UK economy needs and having tighter controls on immigration could provide a potent force in preventing the low skilled and low wage labour market from becoming saturated.

Consequently, leaving the EU might actually help to alleviate income inequality and stimulate consumption in the British economy.

Table 1: Share of total UK income by percentile

One looming economic disaster which might also be alleviated by the decision to leave the EU is the refugee crisis. Under its current obligations, the UK is legally required to allow unrestricted migration of EU citizens into the country.

Presently, Europe is facing an unprecedented influx of refugees, many of whom are granted EU citizenship once they have been processed. Consequently, there are likely to be significant costs associated with integrating and caring for these new migrants.

For example, Germany is already forecasting a 50 Billion euro cost to the country by 2017 as a direct result of the influx of refugees. Similarly, Sweden is expecting to increase public spending by at least 0.5% of national GDP to adequately care for the new arrivals. By severing its legal obligation to allow unrestricted migration, Britain could exert greater control over its immigration policy and weather the crisis more effectively.

In conclusion, the Brexit is a complicated and multi layered decision which UK citizens have the un-enviable burden of having to make. However, whilst much of the media exposure focuses on a plethora of overblown “worst case” scenarios, it is important to remain level headed and look at all sides of the issue.

Teasing apart the true nature of Britain trade relationship with the EU reveals how important the island nation is to the continent. Likewise, understanding the source and purpose of FDI into the UK shows why the EU is not as important in encouraging multinationals to invest in Britain. Finally, taking a closer look at the nature of immigration into the UK can provide a very solid argument as to why the Brexit might actually be a boon to the country.

Ultimately, only time will provide hard answers for many of the questions that the referendum has brought to the surface. However, whatever the people of Britain choose we can be sure the markets will be readying for tumultuous time indeed.