In January, when the Brookings Institute sponsored a forum on “Trading stocks in America: Key Policy Issues.” Gregg E. Berman, Associate Director of the Office of Analytics and Research at the SEC, took part, and used the occasion to advance the view that “the markets are not broken.”

“In spite of what you read everywhere,” he continued, “ in spite of what many market participants say, and in spite of what many jurisdictions and other regulators might say about the equity markets, they’re not broken. I’m convinced of that.”

Vanishing Spreads

Though Berman was not explicit about it, he was riffing here on a phrase, “Broken Markets,” that served as the title of a compelling book by Sal L. Arnuk and Joseph Saluzzi. The argument of the book was that a series of regulatory decisions that began in the mid 1990s is having a range of unhealthy consequences both for retail investors and for the sort of medium-sized company that would once have made an ideal candidate for an IPO.

They had in mind especially the order handling rules (1996), Reg ATS (1998), decimalization (2000), and Reg NMS (2005). Together these changes stitched together a single “national market system” and slimmed almost to the point of disappearance the size of the spreads in that system.

So: are narrower spreads a good thing? Well, according to the broken markets thesis: no. They aren’t. For those fatter spreads paid for something. They did valuable work. The higher spreads won in large part from the fractional nature of minimal ticks in the old days paid for a whole professional network or infrastructure that was essential to the launch of once private companies into the public waters.

So … that is the “broken markets” hypothesis. What does Berman offer to the contrary? A story about a Volkswagen. Not long ago, he says, “My wife and I got dressed up … went to the garage, went to the Volkswagen, turned the key, nothing happened. It didn’t ding. It didn’t do anything.” That, he says, is what it means to say something is broken. Clearly, the markets aren’t in the same condition as a dead VW. On a typical day in the U.S. equity markets “there are somewhere in the order of 5 to 6 billion shares that are traded.”

An Oil Leak

Daniel G. Weaver followed Berman on this panel. Weaver is a professor of finance and economics at Rutgers Business. He began with the observation that though the markets may not be “broken” in the sense of the dead VW, they may nonetheless be in need of “a little tune-up.”

One could go a bit further. Shouldn’t one worry about one’s car’s health before it dies completely? Can’t the word “broken” incorporate situations in which the VW is leaking oil and making load thumping noises for no obvious reason, even if it is still at that point capable of getting its operator from point A to point B? Problems with automobiles have to be addressed short of the full-bore inoperability Berman describes. That’s what Arnuk and Saluzzi themselves have since suggested.

As it happens, a new study by James Upson and Robert Van Ness, of the University of Texas and Mississippi respectively, traces the impact of algorithmic traders on intraday market liquidity, and speaks to the issue of the consequences of those regs enacted in the decade from 1996 to 2005.

Over the last few years, they note, “the role of liquidity supply in the stock market has been filled by Algorithmic Traders (AT).” Their newly central role, the replacement of the old specialists by designated market makers, the implementation of Reg. NMS, and the high velocity of intermarket communications, together with other changes, make it “important to reexamine intraday market behavior for NYSE listed firms.”

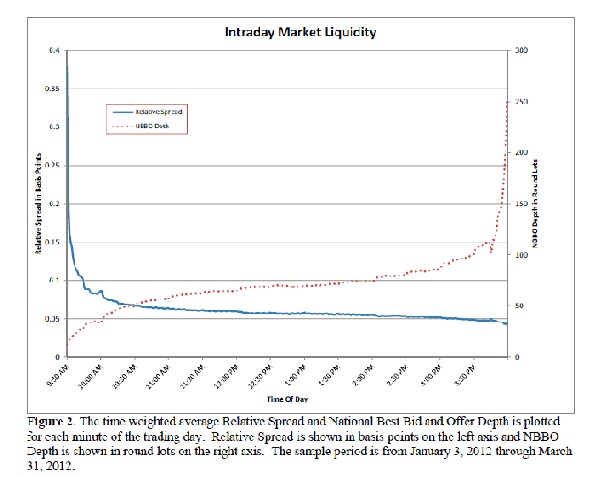

Upson and Ness present evidence that excess algorithmic trading and quote competition between exchanges are in fact drying up liquidity measured as the ratio of NBBO depth to NBBO spread. They trace this to the arms-race aspect of the trend toward high-frequency trading. Liquidity suppliers have to worry that other market participants will get ahead of them in this. Even back in 2008, the TABB Group said that a broker whose e-trading platform fell just 5 milliseconds behind the competitor’s system stood to lose 1 percent or more of its order flow.

Remove the Wrench

Even where a single exchange quotes the best price this latency risk exists, because automated liquidity suppliers engage in quote stuffing, the submission and cancellation of large numbers of orders, thousands per second, and this activity slows down an exchanges ability to handle the ‘real’ orders, those made to be executed.

Liquidity suppliers, Upson and Van Ness observe, “may demand higher spreads and reduce posted liquidity as compensation for the higher latency risk when cross market competition is high.”

Yes, as the chart above indicates, there is an upward spike in NBBO depth at the end of each trading day. But that’s simply because HFTs want to avoid overnight inventory.

So far as I can tell, what these scholars are saying is that oil is leaking out of the Volkswagen, in part at least because of the wrench the SEC threw into the engine.

Though observers may disagree about the best course of automotive maintenance from this point forward, I think one suggestion has an obvious appeal: get the wrench out of the works.