Russia’s economy has been a sore spot for more than two years now. Since the ruble crisis of late 2014 the role of the Bank of Russia has been to apply IMF-style counter-cyclical tightening to stabilize the situation in the wake of the decision to allow the ruble to float freely on the open market.

That was the right decision then. It was the move the U.S. did not expect President Vladimir Putin to make. It was expected Putin would hold to his natural conservatism and keep the ruble trading in the 30’s versus the U.S. dollar as opposed to risking a collapse in exchange rate in the face of an historic drop in oil prices over the eighteen months between July 2014 and the low made in late January 2016.

Oil dropped from $120+ per barrels to around $28 during that period. And if Putin hadn’t proactively allowed the ruble to fall from RUB32 to a high of RUB85 in early 2016 Russia would have been bankrupted completely.

During that time Bank of Russia President Elvira Nabullina raised the benchmark lending rate to 17.00% and Russia began the slow, painful process of de-dollarizing its economy.

It’s been five years since those dramatic times. But a lot of damage was done, not just to the Russian people and their savings but also to the mindset of those in charge at the Bank of Russia.

Nabullina has always been a controversial figure because she is western trained and because the banking system in Russia is still staffed by those who operate along IMF prescriptions on how to deal with crises.

But those IMF rules are there to protect the IMF making the loans to the troubled nation, not to assist the troubled nation actually recover. To explain this, I have to get a bit technical, so bear with me.

The fundamental problem is a miseducation about what interest rates are, and how they interact with inflation and capital flow. Because of this, the medicine for saving an economy in trouble is, more often than not, worse than the disease itself.

If Argentina’s fourth default in twenty years doesn’t prove that to you, nothing will.

Nabullina still believes that her job is to get inflation down to 4%. Inflation targeting, as central bank policy, is a disease that needs to be placed next to smallpox at the CDC in Atlanta.

It seems I have to write this article once every few months just to remind people what the problem is.

When inflation is above the target an austerity mindset dominates at the central bank who keeps interest rates above the market rate in the vain hope they can wring the last bits of inflation out of the economy, because sufficient confidence hasn’t returned to the banking system after the crisis.

This is Russia’s problem today. Nabullina still believes there’s work to be done before allowing the economy to grow.

When inflation is below the target, like in the ECB and the U.S., then to the miseducated central banker growth is sluggish and demands stimulus in the form of cheap money to create a virtuous credit cycle. It hasn’t worked and it won’t work.

Because both of these theories about the effects of inflation targeting are dead wrong.

They haven’t worked in the U.S. and Europe because there is no more capacity within their economies to take on more debt to stimulate demand and increase spending. All they are doing is, as described by Mises and others, “pushing on a string” offering money no one wants at interest rates the market cannot sustain.

That cheap money inflates asset prices like stocks and bonds while diverting capital to long time-horizon projects like fracking in Texas, and housing and car loans, but it thieves working capital from the future by mispricing the risk of those projects in the form of the interest rate.

The net effect is enriching the already obscenely rich and powerful, through wealth transfer which feeds leftist and Marxist criticisms of the ‘free market’ while they proclaim the end of capitalism.

But central bank inflation targeting and control is the height of a centrally-planned economy. Control the value and cost of money and you control the means of production. So, capitalism this ain’t folks.

Miseducation on matters economic are commonplace today from the commanding heights to the lowest barrios.

Eventually, you reach the point we’ve arrived at in the west where no amount of forcing the market, through punitive negative rates, can stimulate growth. This is simply arrogant men praying at the altar of math torturing equations which have no resemblance to reality and turning it into policy.

On the other hand, we have Nabullina trained in this world of econometrics and its econo-babble, holding back the Russian economy with interest rates set above the market. She is either overly-cautious, if I’m being generous, or a full on fifth-columnist stifling growth to support Russia’s enemies, if I’m being cynical.

I think the truth lies somewhere in the middle, if I’m being fair. Today I’ll be fair.

The Russian economy, structurally, is in excellent shape. John Hellevig at the Awara group recently published an excellent report explaining the guts of what’s going on there. And John notes, like I have been for more than a year (here and here), that the Bank of Russia has interest rates too high given what the market is telling it.

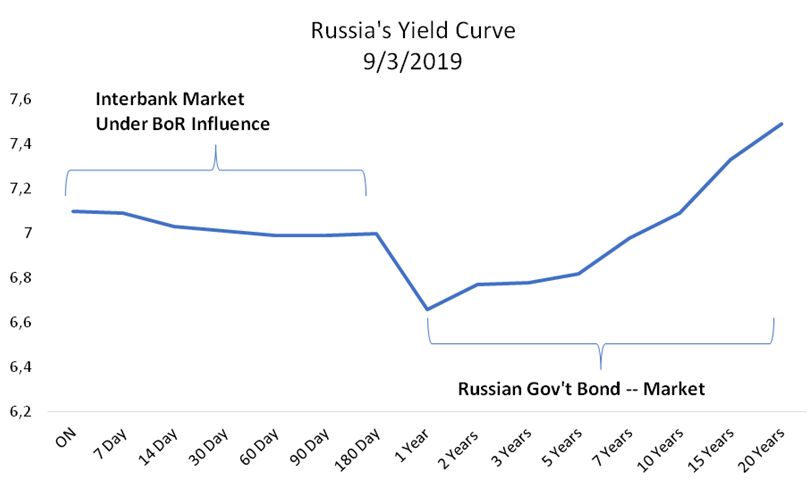

It’s not that tough really, just look at the Russian yield curve and you can see what I’m talking about.

The current benchmark rate in Russia is 7.25%, down from 7.75% just two months ago (and that I’ll get to in a minute). The entire interbank market and short-term deposit market is trading below that benchmark rate.

This means the central bank is holding back a market that wants to trade at lower rates. This is keeping liquidity low and access to loans in the domestic and commercial market low as well.

Meanwhile, the demand for Russian debt, because as a country Russia’s balance sheet is so clean, in part due to Nabullina’s stewardship of the 2014-16 crisis period, is pushing rates lower. And for the first time in close to five years Russia has a normal positively-sloping yield curve from 1-year to 20-years, with no humps or flat spots.

Demand for Russian debt is finally market driven in a way that is predictable and can allow banks to make money paying short and lending long. This is how banks are supposed to make their money, not speculating on stocks and currencies!

Moreover, domestic savings rates at all maturities in the CD and money markets are below the benchmark rate, so Russian banks are under zero stress. High savings offer rates indicate a need to shore up reserves by attracting savings. It’s a bad sign.

Non-performing mortgage loans stand at less than 1%…. 1% !!

The only worry is the outstanding dollar-denominated debt, but that makes up around 1% of the total Russian mortgage market. It’s literally chump change.

I mean, for pity’s sake, what on god’s green earth is Nabullina waiting for? An engraved invitation from the Fed to the next convocation at Jackson Hole? She’s done her job, now let the Russian people do theirs.

Nabullina has kept rates high out of fear of inflation returning due to a rising U.S. dollar and falling oil prices which is putting upward pressure on the ruble. She made an egregious policy error hiking rates in response to Trump’s crazy aluminum tariffs last year. And then held that level until June.

She’s only now just beginning to lower rates after the policy became ludicrous and Russian GDP growth has stalled. Again, incompetence and treason look very similar from a distance.

She keeps jumping at the shadows of a dollar-induced crisis. But the Russian economy of 2019 is not the Russian economy of 2015. Dollar lending has all but evaporated and the major source of demand for dollars domestically are legacy corporate loans not converted to rubles or euros.

So, the Russian economy is so much more insulated from a rise in the dollar than it was before.

The fundamental flaw in the thinking behind most central bankers, especially those trained by the IMF, is that lowering the cost of money stimulates growth and raising it reins it in. It’s an overly simplistic model to explain why we need philosopher kings like Nabullina, Mario Draghi and Jerome Powell to tinker with the economy and engineer growth and stability.

The reality is it’s more complicated than that, because access to capital means different things at different parts of the business cycle to different economies. And Russia’s role in the global economy is changing.

Russia is becoming an independent node in the global economy. Shut out of the U.S. dollar markets, Russia now has to lead the part of the world it dominates – the EAEU, Turkey, Iran, the CSTO states – and show confidence by making the ruble more accessible to foreign investment.

Projecting confidence comes in the form of lowering rates to reflect a healthy domestic market, not keeping rates high because you’re afraid of the U.S.

That yield curve I posted above is a picture of a central bank scared of the future, like Jerome Powell at the Fed, and not one sanguine about Russia’s future prospects. Powell has problems Nabullina doesn’t have, like hundreds of trillions in unfunded future liabilities that require much higher rates to stabilize.

Lowering interest rates in Russia from 7.25% to 6.5% or even 6% is likely all she needs to do and then let the markets take care of things from there. That’s what the market’s actually telling her.

And I believe Vladimir Putin has had enough of Nabullina’s fears. He’s getting more and more impatient with his central bank president. He sees the lack of growth of the Russian economy and wonders why capital formation is locked up behind a wall of overly-high interest rates.

Recently Putin sat down with Nabullina and right after that interest rates dropped 0.25%. The same thing happened in 2015 when she had rates stuck at 10% and Putin had to finally forced her to justify herself.

It’s clear that there is something wrong at the Bank of Russia; whether it’s Nabullina herself, her staff or the legacy of insipid and dangerous Western economic theories refusing to die, is beyond my knowledge.

The cynic in me says the foot-dragging by the Bank of Russia is the final vestige of U.S. infiltration in Russia’s institutions rearing its ugly head. That fight is ongoing, but the recent drops in the benchmark rate are a good start.

This article was previously published at Strategic Culture Foundation