Some emerging market currencies actually trade more like developed market currencies in response to interest rate changes. Let's sort the 'yield shielders' from the 'bond boosters'.

All kinds of classifications exist for currencies: OECD and non-OECD, developed and emerging, G10 and non-G10, reserve currencies and non-reserve currencies, to name just a few. Generally, the groups are distinct and have different trading characteristics, but this is only true for the 'average' currency in the group.

Just like in football, it's hard to get promoted from one league to another. You may need to become a member of an exclusive club first or even adhere to a set of legacy rules that are out of date. But what if we were to ignore all the politics and see how the financial markets actually treat various currencies?

Interest rates are an important driver of currency exchange rates, but the direction is not always clear. Some currencies tend to appreciate when domestic interest rates go up. Let's coin these currencies the 'yield shielders', as foreign investors in domestic bonds of these currencies will typically see the currency gain when bond prices fall.

'Yield shielders' are currencies that tend to appreciate as local interest rates rise

On the other side of the equation we have the 'bond boosters' - currencies that tend to depreciate as local interest rates rise. These currencies generally amplify returns for foreign investors, with the currency tending to gain at the same time as when local bonds rally and vice versa.

However, the main distinguishing feature between 'yield shielders' and 'bond boosters' is the perceived credibility of the central bank in fighting domestic inflation. Independent central banks that don't face political interference and have a history of showing willingness to raise rates when inflation expectations rise will often see the currency strengthen when raising rates. 'Real' rates in this case are more likely to be protected from falling when inflation picks up.

'Bond boosters' are currencies that tend to depreciate as local interest rates rise

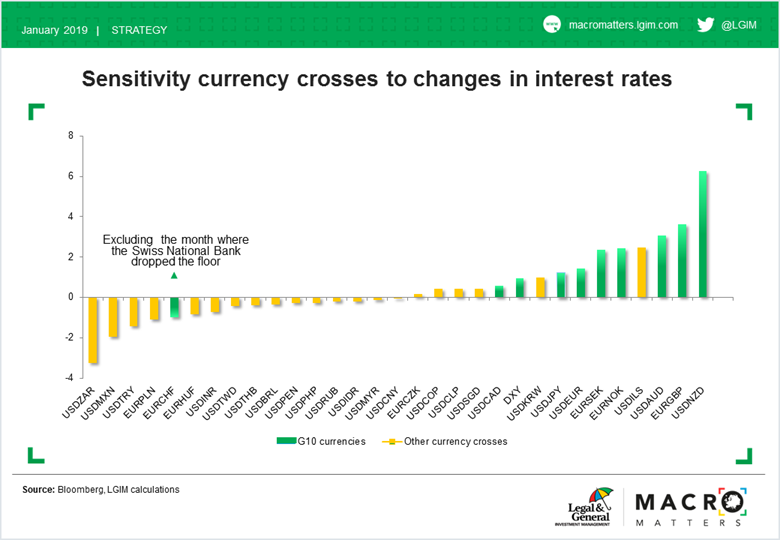

To sort out which currencies fall into which basket, we looked at the historical relationship between currency moves and interest rate changes, with currencies measured against their natural reference currency (generally the US dollar, but the euro for most European currencies). Similarly, we measured rates relative to US interest rates or euro rates. For the US dollar we looked at a trade-weighted basket and 3-month Libor rates.

The chart below shows the results (or more specifically 'regression coefficients') for a number of currency pairs where we have 'regressed' monthly spot price moves since January 2003 onto monthly changes in 3-month interest rate differentials.

Our findings suggest that all G10 currencies (i.e. EUR, GBP, AUD, NZD, USD, CAD, CHF, NOK, SEK, JPY) are 'yield shielders' (right side of the chart) except the Swiss franc, which may be surprising given its safe-haven status. However, the relationship for the Swiss franc is distorted by one extreme observation. Leaving out the month when the currency floor was unexpectedly removed by the Swiss National Bank (January 2015), the Swiss franc moves back with the rest of the G10 pack (green triangle).

There's an argument that the Israeli shekel, South Korean won, Singapore dollar, Chilean peso, Colombian peso and the Czech koruna should be promoted to the Premier League

Most emerging market currencies are 'bond boosters' (left side of the chart), but not all. This is where it becomes interesting, as a number of emerging currencies trade like the developed G10 currencies, and, you could argue, need to be promoted to the Premier League of currencies. These are the Israeli shekel, South Korean won, Singapore dollar, Chilean peso, Colombian peso and Czech koruna (yellow bars from right to left).

Being promoted is one thing, but it's also important to beware the currencies that are at risk of being relegated, as relegation often comes together with currency depreciation.