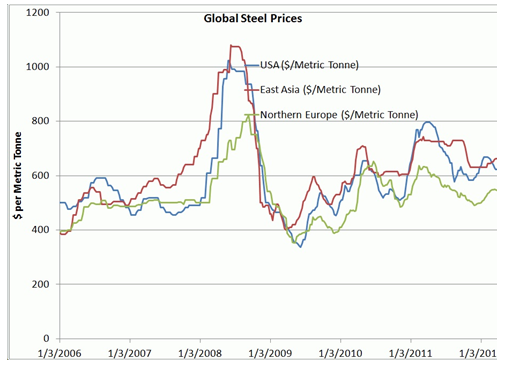

There was no new recession in the US in late 2011 and the European sovereign credit mess did not devolve into a repeat of the 2008-09 financial crisis. An improvement in the outlook for global growth has helped drive a modest uptick in global steel prices and a similarly modest rally in the prices of global steel producing stocks.

To truly understand the dynamics now driving the stock prices of steelmakers, investors must first understand the dynamics of making steel. Steel isn’t a metal but an alloy that’s composed primarily of iron mixed with one or more additional elements that act as hardening agents, making steel far stronger than raw iron.

While the earliest steel artifacts are more than 4,000 years old, ancient production methods were inefficient and produced generally lower grades of steel than are possible today. Steel also was extremely expensive to manufacture and used only in applications where no cheaper alternative existed, such as in the production of swords and cutting tools.

However, a series of technological advancements starting in the mid-19th century turned steel from a niche alloy into a mass-produced industrial product that’s now one of the world’s most important basic materials.

In 2011 alone, the world produced around 1.5 billion metric tons (3.3 trillion pounds) of steel destined for a long list of end uses including residential and commercial construction, automobiles, appliances, energy and industrial machinery.

About 98 percent of all steel produced globally is manufactured using one of two basic processes: oxygen blown and electric furnaces. The main raw material used in an oxygen blown furnace is pig iron, a type of iron that has 2 percent to 4 percent carbon content.

Pig iron is created in what’s known as a blast furnace. In a blast furnace, raw iron ore, consisting primarily of iron mixed with oxygen, is heated to extreme temperatures in the presence of carbon in the form of coke, typically produced from metallurgical coal. The carbon combines with oxygen in the iron ore, to produce carbon dioxide gas, effectively removing the oxygen from the ore. The resultant product is pig iron, a rather brittle and useless substance in its own right.

To create steel from pig iron, much of the carbon and impurities must be removed. In an oxygen furnace, purified oxygen is pumped through molten pig iron. Oxygen bonds with carbon, to produce carbon monoxide, and with other impurities to produce slag that can be removed from the molten metal.

The result is steel, a low carbon and low impurity form of iron. The resultant steel can be alloyed with metals such as tungsten, chromium, molybdenum, and nickel to produce a product with various useful properties such as increased strength, lower weight or resistance to rusting.

In contrast, an electric arc furnace essentially uses electricity to heat scrap steel metal, remove impurities and make steel. Producing steel out of such a furnace is cheaper but requires availability of significant quantities of scrap steel to use as feedstock, so it’s a far more common technology in developed countries such as the US than fast-growing steel consumers such as China.

Worldwide, 70 percent of steel produced is made in oxygen blown furnaces compared to roughly 30 percent in electric arc furnaces. In Asia, the world’s most important steel-producing region, around 81 percent of steel production comes from oxygen blown furnaces. In China, the world’s largest steel-producing country accounting for nearly half of global production, more than 90 percent of steel is produced in oxygen blown furnaces.

By contrast, more developed regions such as the US and European Union are more heavily reliant on electric arc technology, with 61 and 44 percent of steel production respectively made using this technology.

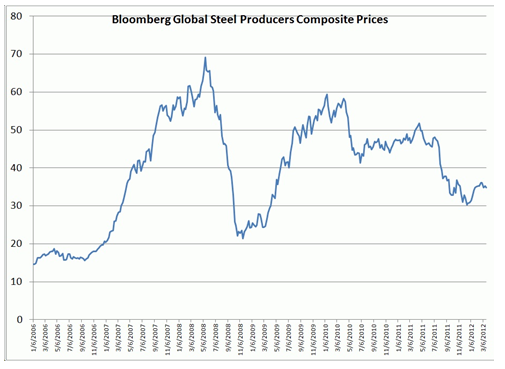

Last year wasn’t kind to steel-producing firms or to steel prices generally. As the chart shows, global steel producers saw gains of more than 100 percent in 2009 and 2010, followed by a near 34 percent pullback in 2011.

As you might expect, the main driver of the 2008-09 slump in steel producer stocks was the global economic downturn and financial crisis that crimped demand for steel. The subsequent recovery, led by growth in the steel-intensive emerging markets, was the main driver of upside for both steel prices and related stocks in 2009 and early 2010.

The downturn in shares of most steel producing companies in 2011 derived from two main factors: concerns about global economic growth sparked by the European financial crisis and rising raw material costs.

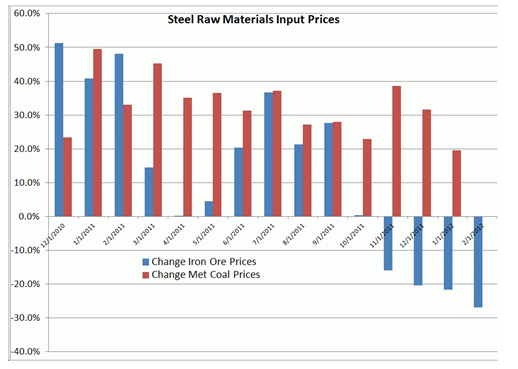

As I note above, the majority of global steel production comes from oxygen blown furnaces, which require two major commodity inputs: iron ore and the metallurgical or “coking” coal used to make coke, a purified form of carbon.

Iron ore and coking coal prices rose rapidly in 2011 on a year-over-year basis, particularly in the first half of the year (see chart above). While steel prices also rose in the first half of the year, the gains were less dramatic.

Steel production isn’t really a mining business but a manufacturing business – producers take raw materials including iron ore and metallurgical coal and use those materials to produce steel. As with any manufacturer, when the value of raw materials rises faster than the value of the product produced, profit margins get squeezed. That’s exactly what happened last year.

The effect was exacerbated by extreme flooding in Australia in the first half of 2011 that disrupted the production and export of both iron ore and metallurgical coal, sending prices soaring globally (see chart).

As concerns about global economic growth and the prospect of a new financial crisis sparked by Europe’s debt woes intensified after the middle of 2011, steel prices sold off sharply. The move was exacerbated by concerns about a slowdown in demand from China prompted by the government’s efforts to cool property prices and speculative construction activity.

Demand: A Look Ahead

China is both the world’s largest consumer and the world’s largest producer of steel, accounting for nearly half of total global production of the alloy. China’s dominance of both sides of the steel industry has been steadily increasing for years and that trend is likely to persist for the foreseeable future.

- English (UK)

- English (India)

- English (Canada)

- English (Australia)

- English (South Africa)

- English (Philippines)

- English (Nigeria)

- Deutsch

- Español (España)

- Español (México)

- Français

- Italiano

- Nederlands

- Português (Portugal)

- Polski

- Português (Brasil)

- Русский

- Türkçe

- العربية

- Ελληνικά

- Svenska

- Suomi

- עברית

- 日本語

- 한국어

- 简体中文

- 繁體中文

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Bahasa Melayu

- ไทย

- Tiếng Việt

- हिंदी

Where Steel Prices Are Headed

Latest comments

Loading next article…

Install Our App

Risk Disclosure: Trading in financial instruments and/or cryptocurrencies involves high risks including the risk of losing some, or all, of your investment amount, and may not be suitable for all investors. Prices of cryptocurrencies are extremely volatile and may be affected by external factors such as financial, regulatory or political events. Trading on margin increases the financial risks.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

© 2007-2025 - Fusion Media Limited. All Rights Reserved.