When a currency peg breaks, it unleashes shock waves of uncertainty and repricing that hit the global financial system like a tsunami.

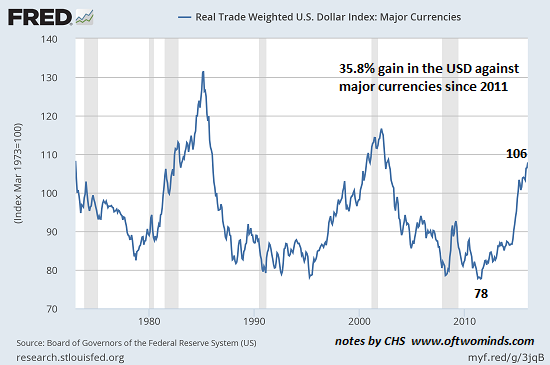

The U.S. dollar has risen by more than 35% against other major trading currencies since mid-2014:

If all currencies floated freely on the global foreign exchange (FX) market, this dramatic rise would have easily predictable consequences: everything other nations import that is priced in dollars (USD) costs 35% more, and everything the U.S. imports from other major trading nations costs 35% less.

But some currencies don't float freely on the global FX markets: they're pegged to the U.S. dollar by their central governments. When a currency is pegged, its value is arbitrarily set by the issuing government/central bank.

For example, in the mid-1990s, the government/central bank of Thailand pegged the Thai currency (the baht) to the USD at the rate of 25 baht to the dollar.

Pegs can be adjusted up or down, depending on a variety of forces. But the main point is the market is only an indirect influence on the peg, not the direct price-discovery mechanism as it is with free-floating currencies.

If central states/banks feel their currency is becoming too strong vis a vis the USD, they can adjust the peg accordingly.

Why do states peg their currency to the U.S. dollar? There are several potential reasons, but the primary one is to piggyback on the stability of the dollar without having to convince the market independently of one's own stability.

Another reason to peg one's currency to the USD is to keep your currency weaker than the market might allow. This weakness helps make your exports to the U.S. cheap / competitive with other nations that have weak currencies.

Nations defend their peg by selling dollars and buying their own currency. The way to understand this is supply and demand: if nobody wants the currency, the demand is low and the price falls. If there is strong demand for a currency, it rises in purchasing power if the supply is limited.

By selling USD and buying their own currency, nations put downward pressure on the dollar and put a floor under their own currency.

The problem is, you need a big stash of dollars to sell when you want to defend your peg. If you run out of dollars (usually held in U.S. Treasury bonds), you can't defend your peg, and the peg breaks.

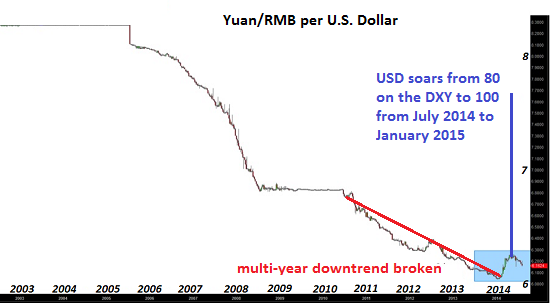

This is why China amassed a $4 trillion stash of U.S. Treasuries. Now that the USD has soared, China's yuan (RMB) has also soared against other currencies because it's pegged to the USD. This has made Chinese goods more expensive in other currencies.

Currently, the government/central bank of China is attempting to adjust its currency peg to weaken the yuan vis a vis the dollar. To avoid showing signs of losing control, China is attempting to defend the yuan against a break in the peg, and it has burned over $700 billion of its stash of USD in the past few months defending the yuan peg.

Here is a chart of the yuan in USD. Note that China moved the peg from 8.3 to 6.8 to the dollar to strengthen the yuan when the U.S. complained that it was undervalued. The yuan rose to 6 to 1 USD in early 2014, and has since started to weaken as the dollar has soared.

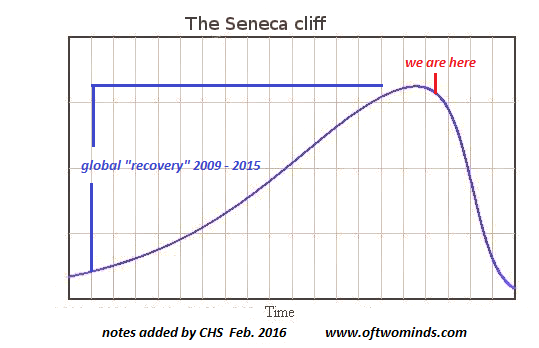

The problem with currency pegs is they have a nasty habit of breaking. The Seneca Cliff offers a model for the way pegs appear stable for a long time and then collapse:

See: Why the Chinese Yuan Will Lose 30% of its Value

When a currency peg breaks, it unleashes shock waves of uncertainty and repricing that hit the global financial system like a tsunami. When Thailand's 25-to-1 peg to the USD broke in 1997, it triggered the Asian Contagion that nearly pushed the world economy into recession.

Now that China's peg to the dollar is under assault, what happens to the global economy when a weakening China finds it can't stop a rapid devaluation of its currency?

Gordon Long and discuss this and other critically important aspects of currency pegs in THE U.S. DOLLAR & THE GLOBAL "PEG PAIN TRADE" (28:36 min.)