The IMF provides the most authoritative report on central bank reserve holdings. It is released at the end of the quarter for the previous quarter. Reserves as of the end of Q1 were released at the end of last week.

Economists and analysts scrutinize the data to see if they can detect shifts in preferences. Hardly a quarter can pass without someone proclaiming the dollar's demise is at hand.

What sometimes gets lost in translation is that the reserve holdings are converted to dollars, which ironically illustrates the greenback preeminence. After all, the reserves could be reported in terms of gold or SDRs.

One implication is that there is a valuation component that needs to be taken into account. Dollar appreciation lowers the dollar value of euro reserves, for example. Also, while central banks may keep part of their reserves fairly liquid, and reports suggest that as many as two dozen own equities, the bulk of reserves are thought to be held in interest-bearing securities. Foreign exchange typically is more volatile than interest rates and is the key to the total return.

The rise and integration of China is perhaps the single most important development in reserves in recent years. China has adopted the best practices at the IMF and has reported the allocation of its reserves. They were gradually bled into the IMF's data, which helped protect the confidentiality of its holdings. The share of reserves for which the allocation was not reported peaked in Q4 13 near. China may have begun reporting its allocation in early 2015, and the share of unallocated reserves fell below 6% for the first time.

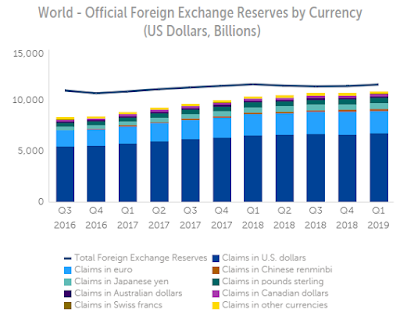

The Chinese yuan's share of allocated reserves is a little less than 2%. When it was first broken out from the catch-all "other" category in Q4 2016, it accounted for about a little more than 1%. The yuan was included in the SDR 1 October 2016. Its share has surpassed that of the Australian and Canadian dollars, and the Swiss franc. In some quarters, the yuan accounted for a significant percentage of the increase in allocated reserves. For example, in Q4 18, the dollar's value of yuan reserve holdings rose by nearly $10.5 bln, while allocated reserves as a whole increased by a little more than $20 bln. In Q1 19, the dollar value of yuan reserves increased by $9.8 bln, which 5.7% of the overall increase in reserve assets.

The use of the yuan as a reserve asset is still small. Consider the scale. Since the yuan has been identified in the IMF's tables (Q4 16), the dollar of value of yuan-denominated reserves has risen from around $90.5 bln to almost $213 bln in Q1 19. While yuan reserves rose $122.5 bln, the reserves held in dollars rose $1.24 trillion (~$5.50 trillion to $6.74 trillion), ten-times more.

The dollar's share of reserves has slipped over this period from about 65.4% to 61.8%. It is not just China, but the euro, yen, and sterling also saw a small increase in their shares. The Australian and Canadian dollars, alongside the Swiss franc, so some slippage. Could this be diversifying away from the dollar? Possibly, but doubtful. First, some central banks, notably Russia, has dramatically cut its US Treasury holdings. Second, other central banks have felt compelled to intervene in the foreign exchange market, and this is often done by selling US dollars. Third, short-term movement can be very noisy. Consider than in Q1 19, the dollar holdings rose by nearly $122 bln, accounting for a little more than 70% of the increase in allocated reserves.

The U.S. dollar's share of reserves outstrips the size of its GDP some argue to explain why diversification and a lower dollar are inevitable. Yet the share of many reserve currencies exceeds their share of world GDP. Along those lines, though to the U.S. GDP, it would seem only fair and accurate to add to it the GDP of countries that tie themselves to the dollar.

At the end of the day, the collective wisdom of the world's reserve managers to hold 60%-65% of its reserves in dollars and 20%-25% in euros.

Bolted on the dominating duopoly is a smattering of a handful of currencies, among which is the yuan. Is the yuan on an inexorable trend toward a greater share of reserves? That seems to be what many believe. The market may be leading officials. Chinese mainland shares are an increasing part of MSCI's EM index and other benchmarks. Mainland bonds are included in bond benchmarks, like the Bloomberg-Barclay's index. However, the yuan's share of SWIFT payments suggests a different story. It peaked in August 2015 just below 2.8%. May's data were reported last week, and the yuan's share was at 1.95% (coincidentally roughly the same as the yuan's share of reserves).