Initial Public Offerings (IPOs) are riding high right now.

You might’ve heard about the Snowflake (NYSE:SNOW) IPO making headlines.

It’s a company with a special type of deal structure that most investors might not have heard of before.

Leading the charge and fury in the IPO markets are SPACs, (Special Purpose Acquisition Companies).

SPACs start as a shell company and sell shares to investors. It doesn’t have any operations or business of its own. The purpose is to acquire one that does.

It’s like a backdoor route for large sums of money (think $100 million, or more) to get into the stock market.

Investors and the private equity funds behind these SPACs love it, because there is much less underwriting, and the paper pushing process through the SEC is easier.

Much like private placements in the red-hot mining space–which we’ll get to in a moment–SPACs have rules.

- SPAC’s have a deadline of 24 months to acquire a business.

- If they don’t, investors get their money back with interest.

- You can also request your money back if you don’t like the acquisition.

However, you can make money with SPACs—and quickly.

Anyone that invested in the VectoIQ SPAC before or during its acquisition of Nikola Motors could have made 10x returns.

We recently alerted subscribers to a SPAC in the Katusa’s Resource Opportunities newsletter portfolio.

It's been up by as much as 30% since the first research report.

With all the headlines, we could expect that IPOs will flood the market.

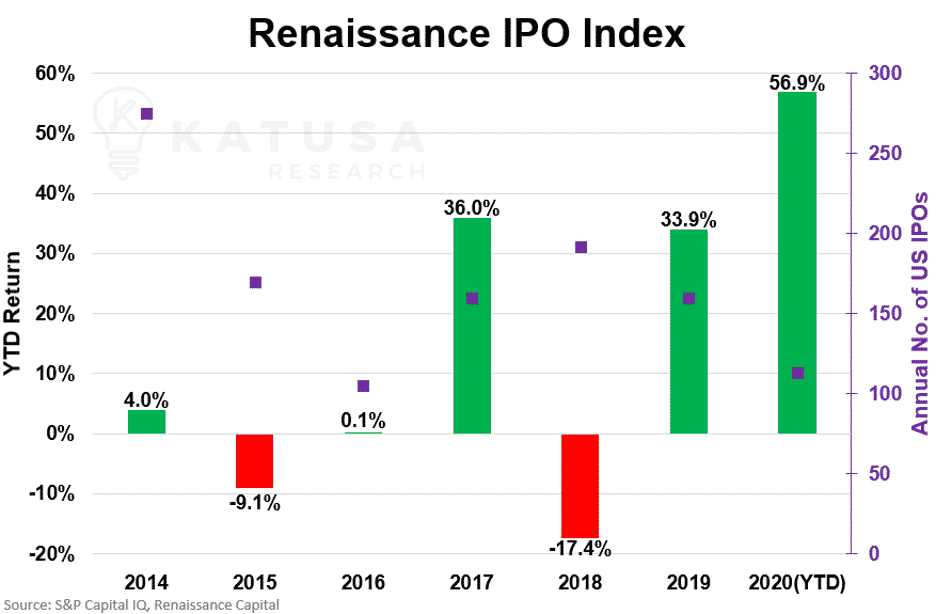

In fact, in the next chart you’ll see that YTD in 2020 we’ve seen the 2nd lowest number of IPOs (113) in 6 years.

But the return of those IPOs through the lens of the Renaissance IPO index is much higher than the last 6 years.

What Happens When New Paper Shares Are Created?

Capital flows are one of the least understood, most closely guarded secrets in the resource sector.

Bull and bear markets are driven by expansions and contractions in capital flows.

This capital comes from everyone—retail investors all the way to trillion-dollar sovereign wealth funds.

Knowing how to profit from these tidal changes in the market is incredibly important for the contrarian investor.

We have all heard a few marquee lines related to trading:

- "Buy when there’s blood in the streets."

- "The market can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent."

- "You know it’s time to sell when shoeshine boys give you stock tips."

I want to talk about the last one…

Being a good seller is as important as being a good buyer and stock picker.

Realizing a profit is important, but selling is a lot more than placing a market sell order for your entire position and moving on.

Selling should be just like an alligator: Slow. Methodical. Strategic.

Always use limit orders.

Let the buyers come to you.

Discipline is required, when buying and selling shares.

And here’s why…

How to Prepare for Amateur Hour…

I want to use my points above to help you understand how fund managers (who get redemptions) and amateur investors sell and put pressure on a stock.

My expertise is in finding and getting myself and my subscribers into resource deals in gold, oil, copper, uranium and silver.

We are coming into the last few months of a year—that has seen share prices of good and bad gold deals soar because of the rise in the gold price.

Throw in a U.S. Presidential election… I believe we are going to see pressure on many resource stocks.

Now, this could be a major opportunity for us.

Let’s start with how much capital has been raised in the metals and mining sector.

Last year, we saw equity financings rise above CAD$12 billion for the sector—a value not seen since the last run up from 2009–2011.

2019’s spike was due in large part to Katanga Mining’s CAD$7.6 billion rights offering.

If you remove that…

Equity financings totaled just CAD$4.9 billion, which would make 2019 the worst year since 2008 when the TSX began releasing statistics.

It was a very tough year for many companies.

2020 will be an improvement. Gold has performed well, and financings are already approaching CAD$4 billion.

What’s more important is what these financings represented versus the sector’s market capitalization.