The Fed promised that the quantitative easing would be only temporary and that it would reduce its ballooned balance sheet to the pre-crisis level. Now, as the Fed adopted an interest targeting with ample-reserves, we know that this is not going to happen. We invite you to read our today’s article about the new Fed’s regime and find out how it works and what it implies for the U.S. monetary policy and the precious metals.

The discussion about the U.S. monetary policy concentrates on the changes in the interest rates and Fed's balance sheet. But what is also very important is how the U.S. central bank implements its monetary policy, especially that in recent years the Fed has started operating in a new monetary policy implementation regime. Let's analyze that change and its implications for the economy and the gold market.

Before the bankruptcy of the Lehman Brothers, life was simple. And the economic textbooks adequately described how the U.S. central bank conducted the monetary policy. In short, the FOMC set a target for the federal funds rate and reached that target through small purchases and sales of securities in the open market. The commercial banks had to hold some reserve balances to meet the reserve requirements. Banks who lacked these reserves, borrowed them in the federal funds market from banks who had excess liquidity. As the reserves were scarce, the Fed could affect the level of the federal funds rate and move it to the target level through changes in the supply of reserves, known as open market operations. For example, when the Fed observed that the market rate is above the target, it purchased the government bonds adding reserve balances to the banking system and creating downward pressure on the market rate.

However, the global financial crisis has substantially affected the Fed's operational framework. To combat the Great Recession, the U.S. central bank carried out a series of quantitative easing programs, buying securities worth almost $4 trillion. The purchases ballooned the Fed's balance sheet and injected a massive liquidity into the banking system. This is very important because the open market operations could not work any longer. As the Fed itself explains,

in an environment with a superabundant level of reserves, the Federal Reserve can no longer rely on small changes in the supply of aggregate reserves to adjust the level of the federal funds rate.

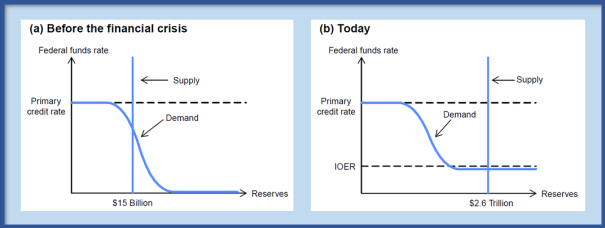

The figure below illustrates both frameworks. Before the economic crisis, the Fed operated along the steep part of the demand curve, while in an ample-reserves regime we have today, the U.S. central bank operates along the flatter part of the curve.

Chart 1: The commercial banks' demand for and the Fed's supply of reserve balances before and after the Great Recession. Source: Federal Reserve

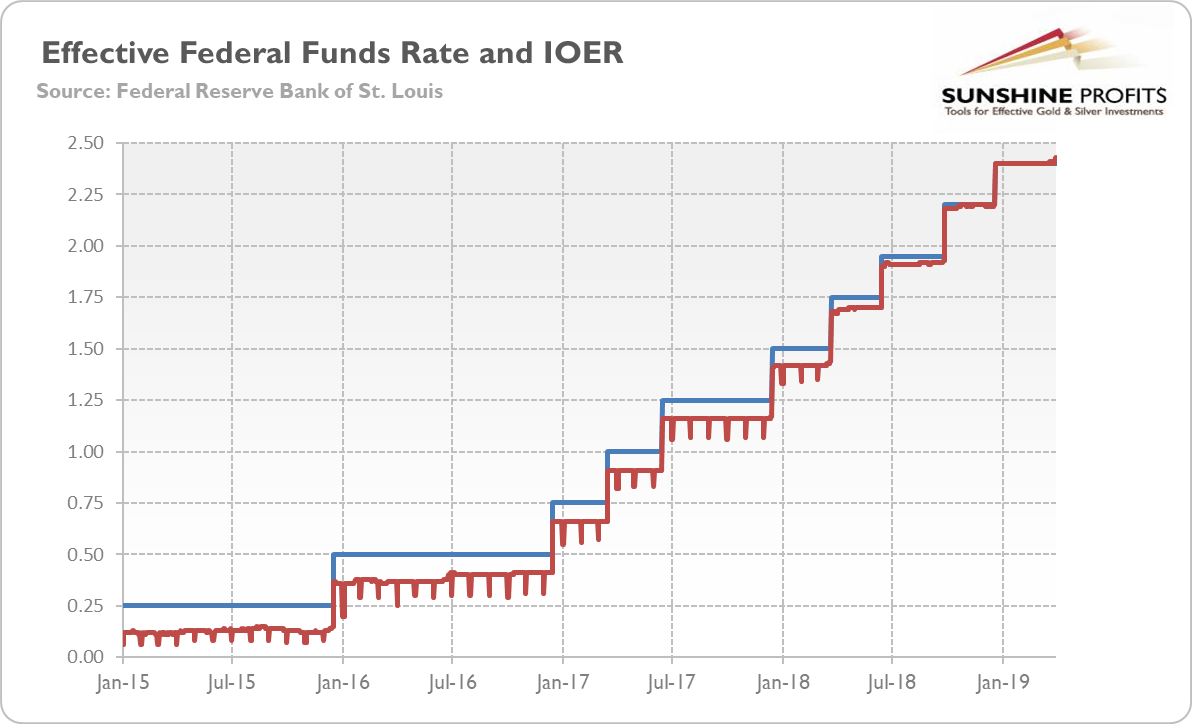

So how the Fed implements its monetary policy decisions now? The U.S. central bank moves the federal funds rate into the target range set mainly by adjusting the rate of interest on excess reserves, or the IOER (and also the offered rate at the overnight reverse repurchases agreement facility, or the ON RRP). For example, when the Fed increases the IOER, banks have an incentive to borrow in the federal funds market at rates below the IOER rate and place those balances at the Fed to earn the IOER. That arbitrage put upward pressure on the federal funds rate. This is why the FOMC raised the IOER in tandem with the target for the federal funds rate over the current tightening cycle, as the chart below shows.

Chart 2: Effective federal funds rate (red line, in %) and the IOER (blue line, in %) from January 2015 to March 2019.

Great, but what does it imply for the monetary policy, economy and the precious metals market? Well, the ample-reserves regime offers a few advantages for the conduct of monetary policy. First of all, it is a simple regime, which does not require sizable daily interventions by the central bank. Moreover, the new system gives the Fed the freedom to use its balance sheet independently from its interest rate policy, removing the tension between stabilizing markets in times of crisis and interest rate control. If it strengthens the effectiveness of monetary policy, then the recessions may be softer, which is bad for gold, which shines the most during severe economic slumps.

The bottom line is the Fed does not rely on open market operations any longer, but on the IOER. Some analysts believe that the new framework is a drag for the economy, as commercial banks have motivation to keep excess reserves at the Fed instead of granting loans to the real economy. However, such claims result from the misunderstanding of the current banking system. The total amount of reserves is determined by the Fed and the commercial banks cannot lend them out.

The new regime based on the IOER was implemented to efficiently administer a monetary policy in an environment of ample liquidity. And, indeed, the Fed has been very effective so far at controlling short-term interest rates, hiking them several times despite the massive amount of banks' reserves.

However, the key question is why the Fed does not want to drain the excess liquidity and return to the pre-crisis regime? The answer is that the U.S. central bank does not want to normalize its balance sheet as it promised earlier (it will be reduced, but not to a pre-crisis level), because it does not want to upset the Wall Street. You see, under current regime, the U.S. central banks can inject liquidity without causing a decline in its targeted policy rate, which facilitates transition to QE if necessary.

The implication for the gold market is clear. When the next economic crisis hits, the Fed will quickly carry out the new round of quantitative easing. If history is any guide, gold should shine during the initial round of asset purchases. However, investors should remember that in 2008, quantitative easing was an unconventional program, so market participants were afraid and turned into the precious metals. Now, we all got used to the QE, so its next round, if not accompanied by the new monetary policy tool, may not spur a rally in gold.