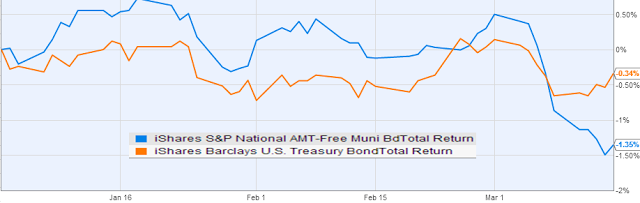

Municipal bonds came under pressure last week, pushing the asset class into the red for the year. And it hasn't just been the recent rise in longer term Treasury yields driving the selloff.

On a year-to-date basis, munis now materially trail Treasuries. Some investors attribute this to seasonal factors such as sellers raising money to pay taxes.

All of a sudden people realized they have a tax liability? Right. What's really pushing these bonds lower?

There is a sad notion in Washington that requiring the wealthy, many of whom have substantial positions in munis, to pay taxes on their muni holdings will raise federal tax revenue. In reality the wealthy will simply rotate out of the muni market, forcing states and municipalities to pay significantly higher rates. And the revenue side of the equation will not increase substantially - instead forcing more capital into offshore tax exempt life insurance and annuity-based estate structures.

Nevertheless we all know how Washington operates. Fears of tax changes in the upcoming budget negotiations - as the debt ceiling debates approach - has contributed to munis trading lower. In fact, according to Morgan Stanley, the chances of muni bonds losing tax exempt status are at 30% (see post from Barron's).

Tulsa World: - The battle that took place over the "fiscal cliff" foreshadowed the current fights that Congress and the president are having over taxes and spending as Congress bumped up against the March deadlines on raising the debt limit, funding the government and automatic spending cuts that were delayed as part of the fiscal cliff deal.

Congress will likely consider sweeping changes to the federal income tax system either as part of this round of budget talks or in the context of comprehensive tax reform. These changes could include a revision to the current federal tax treatment of interest paid on municipal bonds.

Other threats to the muni markets are coming from state governments lowering taxes to attract families and businesses.

Barron's: - Now, proposals have surfaced to cut or eliminate state income taxes in Arkansas, Indiana, Iowa, Louisiana, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, and Wisconsin. Two factors give such proposals a decent chance. First, 39 states now have one-party control of their legislatures and governorships, the most since 1952, and 24 of these are controlled by Republicans, the party pushing hardest for lower income tax rates.

The second factor is competition. Kansas Gov. Sam Brownback succeeded last year in slashing tax rates for high earners and eliminating them for many businesses in what he calls a path to zero income tax. The cuts will cost the state more than $850 million a year in revenue, which Brownback hopes to offset by extending a sales tax that's set to expire and ending some deductions. A tax cut in one state forces neighboring ones to consider following suit in order to avoid seeing high-income residents defect, says Heckman.

These are positive developments that should generate incremental economic activity in these states. However, should the economy in any of these states take a turn for the worse for some reason, state budgets could be in trouble.

What really spooked the muni markets however was the risk of underfunded state pensions. Pension funds tend to use archaic discounting methods that make the present value of their liabilities (expected payouts on pensions) look significantly lower than they really are. As pension asset returns remain weak, pension funds may require unplanned injections of capital to cover the liabilities.

And when it comes to funding state pensions vs. paying on municipal debt, we all know which road state politicians and the unions who often control them will take. What's particularly troubling is that states are not above hiding pension problems in order to sell their bonds. In the case of Illinois (as well as NJ in 2010), the SEC called this lack of disclosure fraud. Market participants are asking if there are other such situations out there.

CNN: - The Securities and Exchange Commission and the Illinois state government have reached a settlement over charges that the state defrauded investors by not giving them proper information about its pension funds.

The SEC, which disclosed the charges with a filing Monday, said the fraud occurred between 2005 and 2009 when the state sold $2.2 billion in bonds without disclosing the impact of problems with its pension funding schedule. There were no fines or penalties against the state as part of the settlement.

"Municipal investors are no less entitled to truthful risk disclosures than other investors," said George S. Canellos, acting director of the SEC's Division of Enforcement. "Time after time, Illinois failed to inform its bond investors about the risk to its financial condition posed by the structural underfunding of its pension system."

The impact of course is not limited to the lower rated bonds like Illinois. The AAA muni bond yield hit a level not seen in almost a year (chart below). And as investors become jittery about long-term rates in general, the muni market will fall under increased scrutiny.

- English (UK)

- English (India)

- English (Canada)

- English (Australia)

- English (South Africa)

- English (Philippines)

- English (Nigeria)

- Deutsch

- Español (España)

- Español (México)

- Français

- Italiano

- Nederlands

- Português (Portugal)

- Polski

- Português (Brasil)

- Русский

- Türkçe

- العربية

- Ελληνικά

- Svenska

- Suomi

- עברית

- 日本語

- 한국어

- 简体中文

- 繁體中文

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Bahasa Melayu

- ไทย

- Tiếng Việt

- हिंदी

What's Causing The Sell-Off In Muni Bonds?

Published 03/18/2013, 01:45 AM

Updated 07/09/2023, 06:31 AM

What's Causing The Sell-Off In Muni Bonds?

Latest comments

Loading next article…

Install Our App

Risk Disclosure: Trading in financial instruments and/or cryptocurrencies involves high risks including the risk of losing some, or all, of your investment amount, and may not be suitable for all investors. Prices of cryptocurrencies are extremely volatile and may be affected by external factors such as financial, regulatory or political events. Trading on margin increases the financial risks.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

© 2007-2025 - Fusion Media Limited. All Rights Reserved.