Nearly four years ago Barclays introduced VXX, the first volatility Exchange Traded Product (ETP). Since that time 5 other companies in addition to Barclays have entered the volatility business. All together they have introduced 35 volatility funds.

It hasn’t been pretty. Of those 35 funds, 15 have been discontinued/terminated and almost half of the remaining 19 are either below critical mass with less than $10 million in assets, or not recommended. VXX has reverse split 4:1 twice, declining from a split adjusted $1600 inception price to $33 in October 2012, a decline of 97.9%—earning it numerous nominations as the top ETF wealth destroyer. And VelocityShares’ TVIX (2X short term volatility) generated monumental amounts of bad press in early 2012 when its price rose almost 100% over its indicative value when Credit Suisse, TVIX’s issuer, suspended share creation, only to plunge 50% when Credit Suisse resumed partial creations a month later—vaporizing at least $270 million in capital in less than a day.

Other than that business has been good.

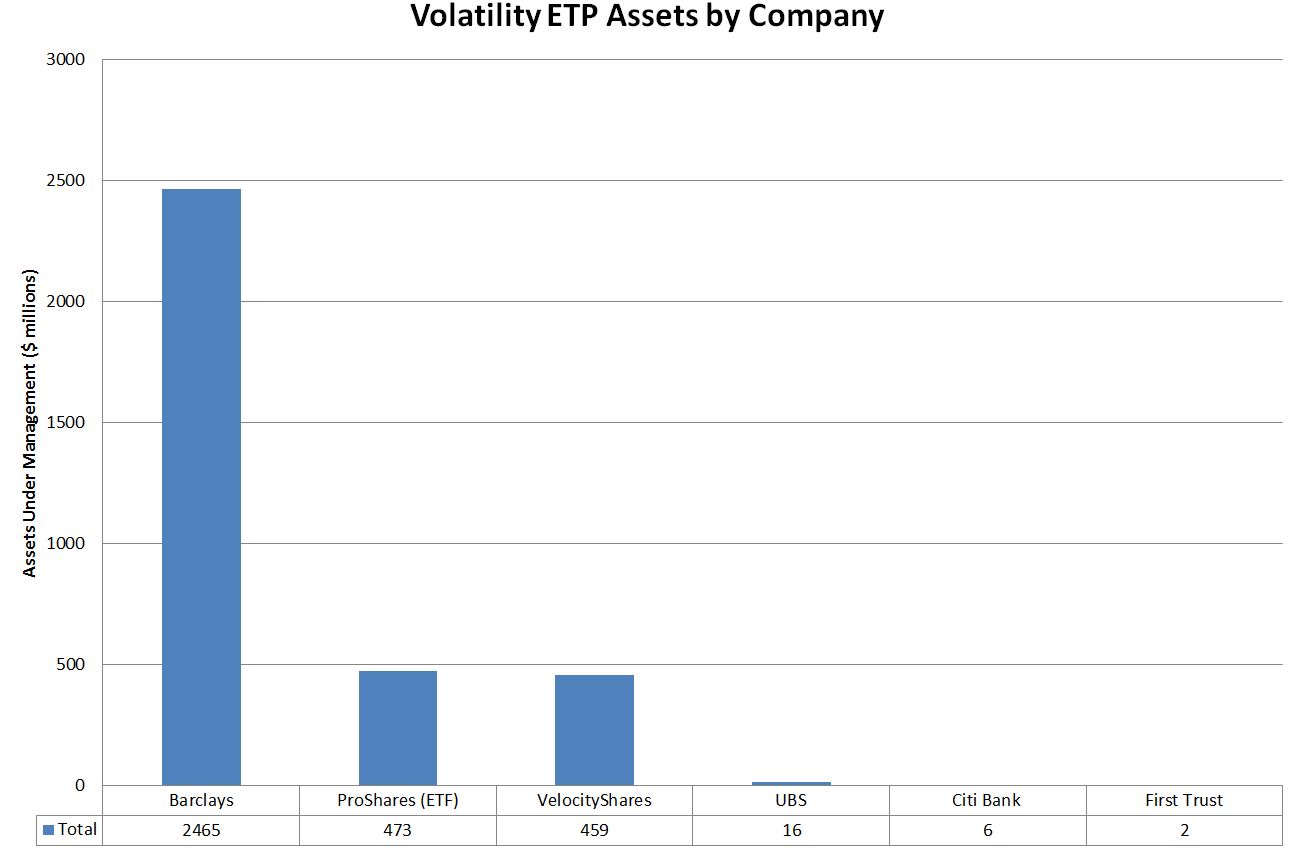

The chart below shows assets under management (AUM) for the 6 players in the market as of the 14th of October, 2012:

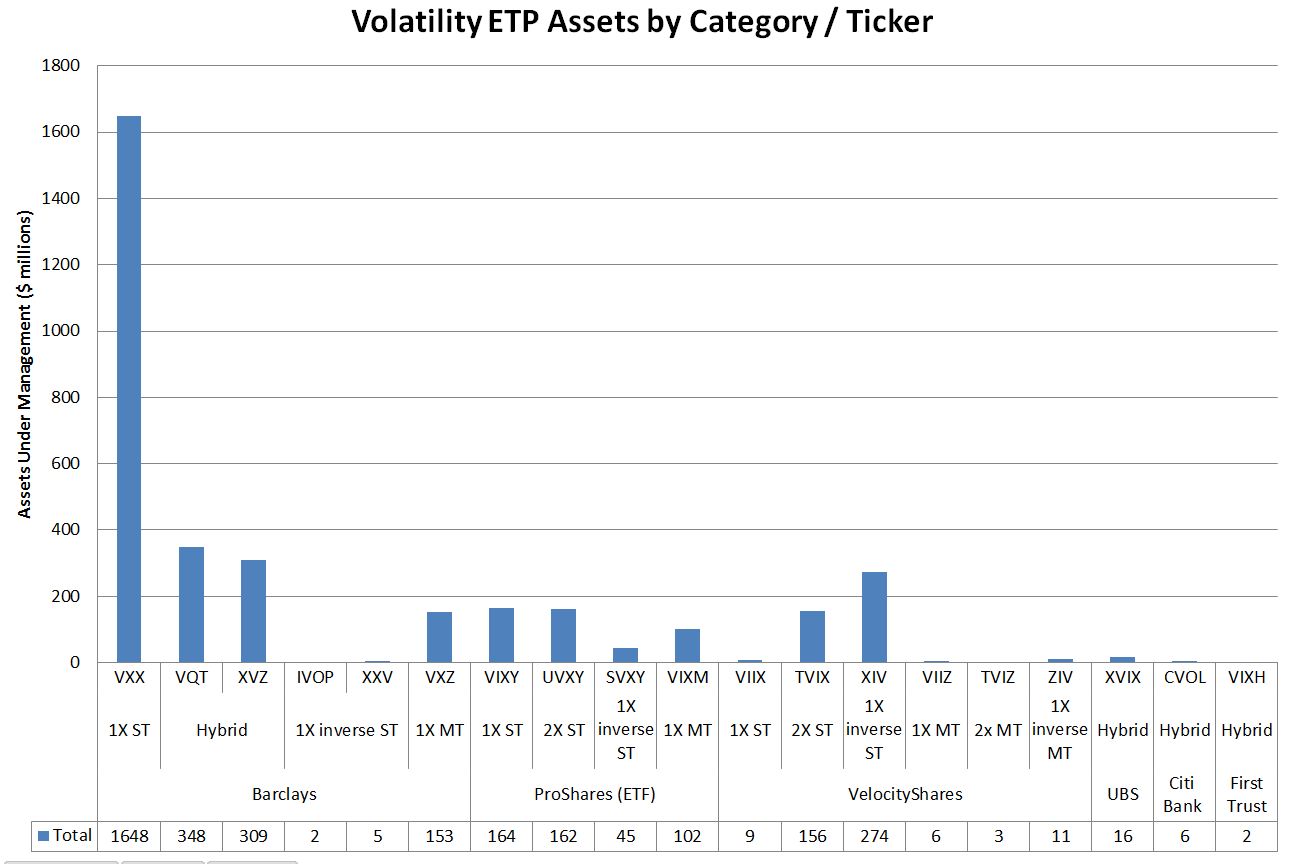

The overall AUM has grown to $3.4 billion, with Barclays holding $2.4 billion and ProShares and VelocityShares tied for second with almost $500 million each. Looking at the AUM breakout at the fund level yields some surprises:

- The rise of the hybrid. I define hybrids as being composed of two or more different fund / securities types. VQT for example has the S&P 500 + a variable allocation of 1X short term volatility (essentially VXX), XVZ has variable allocations of 1X short term long & short and 1X medium term volatility. Hybrid funds now comprise 20% ($681 million) of the volatility fund market even though they have only been around for two years or less.

- Barclays strikes out in the inverse and leveraged category. Evidently Barclays does not believe in daily reset inverse or leveraged funds. Instead, they have offered a series of funds that offer 1X inverse or 2X leverage at inception, but don’t maintain that same leverage factor as the underlying volatility futures move. These funds behave this way because they aren’t rebalanced. Barclay doesn’t have to commit any additional capital to adjust the leverage factor. This is convenient/safe for Barclays, but not so much for customers. The leverage factor increases when the market is moving against a fund, and decreases when the market moves for a fund. The increased leverage tends to slam funds against their termination values, killing Barclays’ IVO, VZZ, and VZZB funds, and strands other funds, XXV and IVOP in sluggo land, with awful leverage factors (or “participation” as they call it). Currently IVOP‘s participation is 0.12, XXV‘s is 0.04.

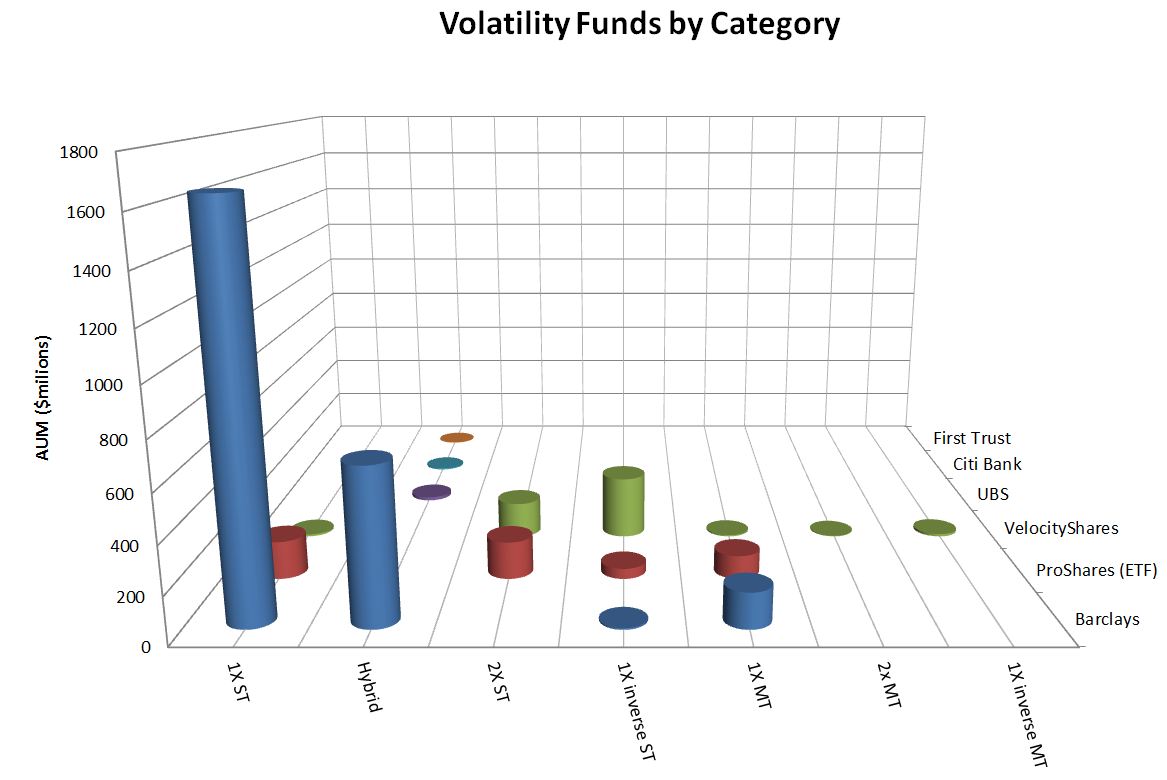

This next chart maps volatility fund categories against company.

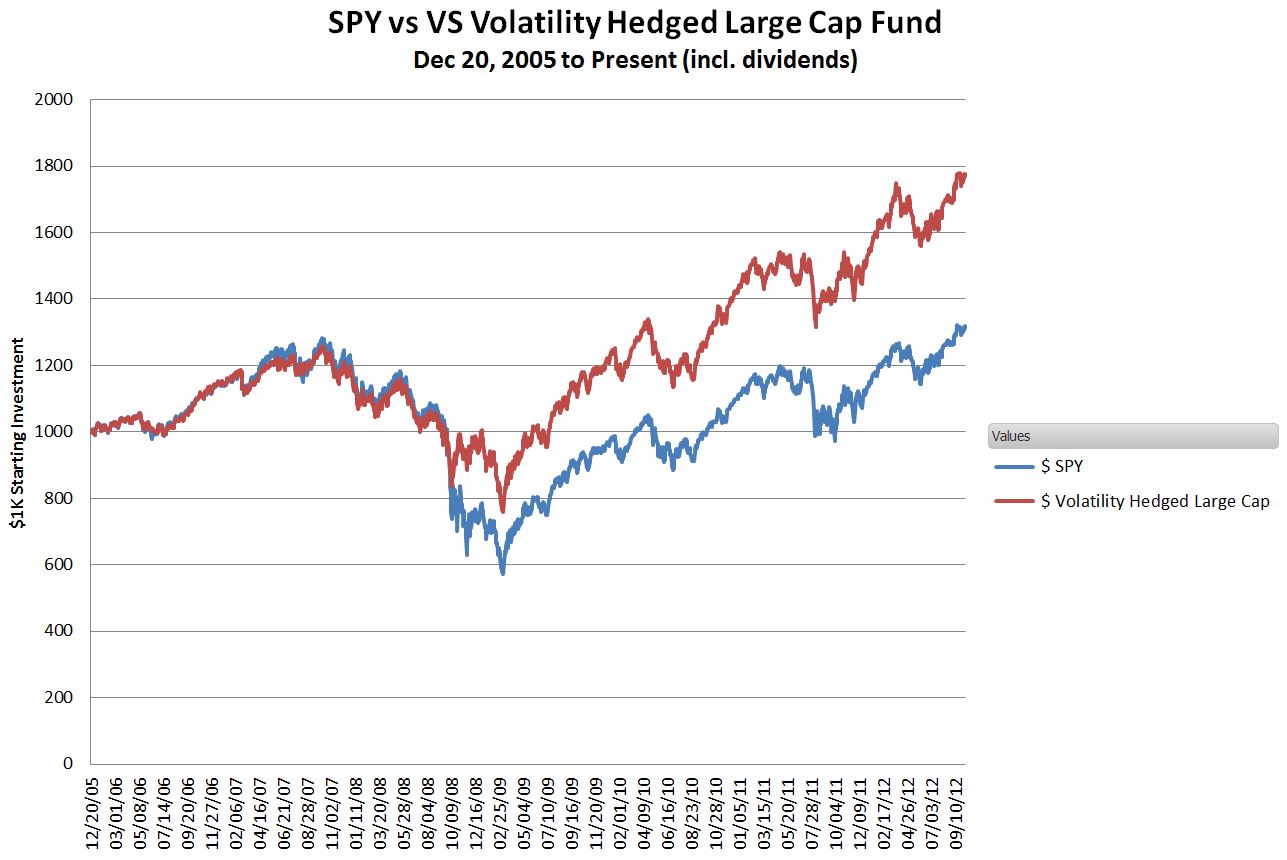

Both ProShares and VelocityShares lack products in the fast growing hybrid category. Pending SEC approval VelocityShares plans to address that gap with two new products. I’ll post more on them in the future, but my analysis shows that these funds are designed to match or exceed the gains of the S&P 500, but with less volatility and risk. My backtest of the VelocityShares Volatility Hedged Large Cap Index is shown below.

Looking forward:

- It looks like Credit Suisse will not reverse split TVIX—dooming it to a slide below $1 and ultimate delisting. ProShares’ UVXY will probably pick up most of TVIX’s current customer base

- As a company ProShares seems to focus on leveraged funds for existing indexes. I doubt they will enter the volatility hybrid category.

- The dramatic increases in mid-term volatility contango will damage Barclays’ XVZ performance and make VelocityShares’ ZIV inverse mid-term fund more attractive. We may see new funds that attempt to capitalize on mid-term contango by investing in inverse volatility during non-panicky market conditions.

- New dynamic volatility funds may move away from using fixed parameters (e.g., XVIX, VQT, XVZ), established by backtesting to allocating by recent behavior (e.g., last year’s volatility/term structures). The parameters established by backtesting can’t adapt to changing market conditions.