Inflationary pressures are building in the U.S., data released this week shows, and this should tilt the Federal Reserve to its more hawkish plan for two more rate hikes this year. But given the Fed’s concept of 'symmetric' inflation, it will not lead the central bank to slam on the brakes.

Federal Open Market Committee members want a certain level of inflation to give the economy some breathing room. Worries last year were more about the risk of deflation, as prices refused to budge. The FOMC also pays a lot of attention to inflation expectations. Their first task was to get expectations up to a level consistent with their target. Now, the challenge is to raise rates enough to rein in actual price increases without depressing those expectations.

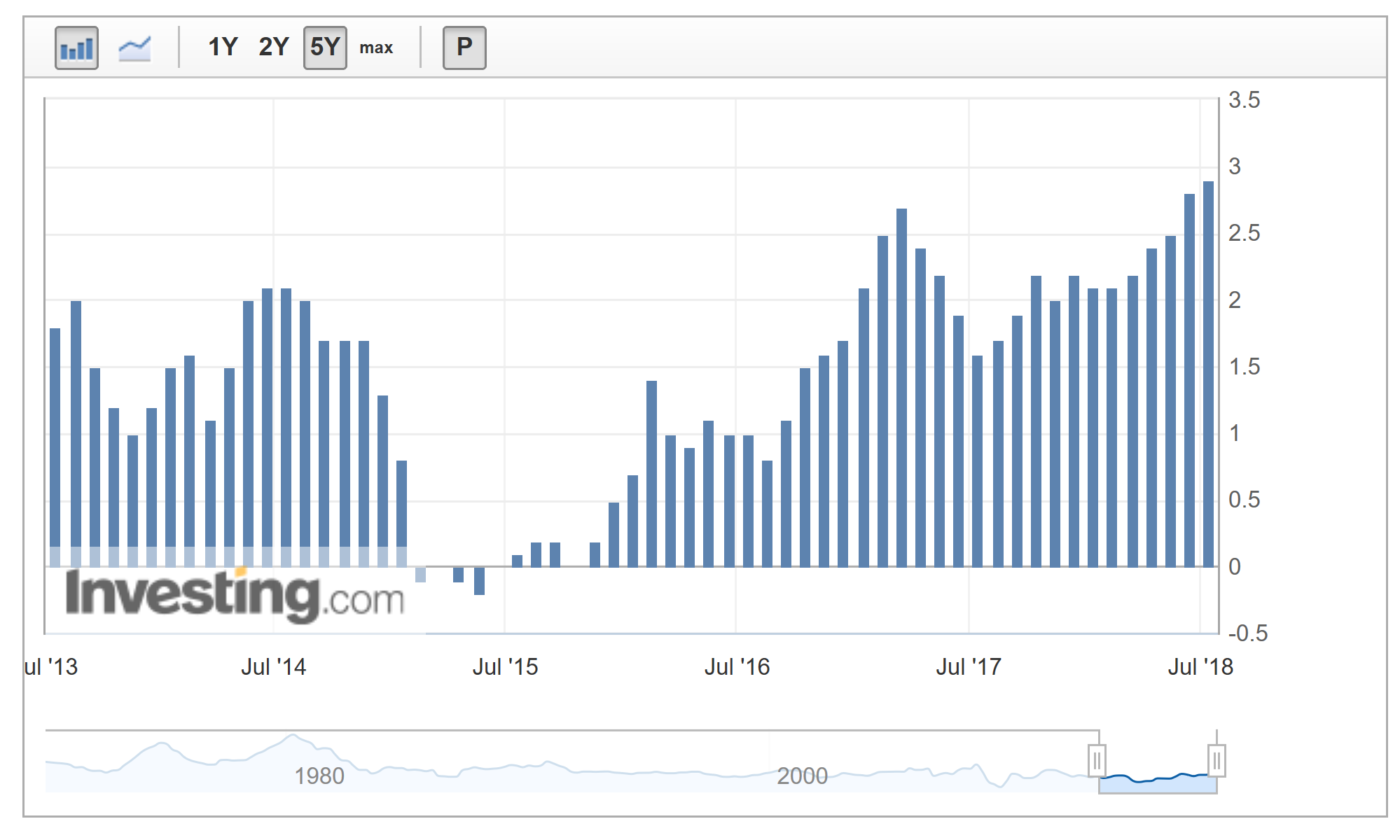

The producer price index (PPI) and the consumer price index (CPI) showed June inflation reached the highest levels in more than six years. And the Fed’s preferred inflation indicator, personal consumption expenditures (PCE), was up in May. PCE rose 2.3% on the year, with core inflation measuring 2%.

But Chicago Fed President Charles Evans wasn’t fazed by that increase. In a wide-ranging interview with The Wall Street Journal earlier this week, Evans was happy enough that inflation had finally gotten back up to the Fed’s 2% target and he said the outlook for sustaining that level of price increases was good.

PPI, sometimes referred to as wholesale prices, was up 0.3% on the month in June and up 3.4% percent on the year, compared with 3.1% in May. But the core inflation on this measure – stripping out volatile food, energy and trade margins – was only 2.7% on the year, though also 0.3% on the month. PPI is a leading indicator because it reflects price increases that will mostly be passed on to consumers in coming months.

The CPI released on Thursday showed a similar increase, rising to a 2.9% annual rate in June from 2.8% in May. The increase was in line with expectations. Core inflation, leaving out food and energy, was 2.3% in June.

CPI is the headline inflation rate, but it tends to run a little higher than PCE. Fed policymakers prefer the latter because they believe it more accurately reflects what people actually spend money on.

Note, though, the Fed policymakers put almost as much emphasis on inflation expectations as on the actual price increases. It is the combination of the two, Evans explained in his interview, that helps the Fed find the “neutral rate” – the interest-rate level that will neither stimulate nor restrain the economy. These expectations are at a good level, Evans said, though he would like to see them even a bit higher.

The New York Fed’s monthly Survey of Consumer Expectations, released on Monday, found inflation expectations in June unchanged from the previous two months, at 3% for both the one-year and three-year horizons. The closely-watched University of Michigan survey also found inflation expectations edging up to 3% percent in June. But that is the highest level since March 2015.

Still, as long as these expectations remain anchored, the Fed should view a temporary overshoot of its 2% target with equanimity.

“I would say that symmetric 2% inflation target would mean that you’re averaging 2% over a long period of time,” Evans said.

Averaging over a 10-year period, after a long stretch when inflation was below the target, would indicate a similar stretch of running slightly over that. The point, the Chicago Fed chief said, is to keep expectations anchored and to preserve the Fed’s credibility that 2% is a target and not a ceiling.