Investing.com’s stocks of the week

The recent soft patch in growth and dovish shift from the Fed has made it less likely that the US enters recession next year.

Six months ago, my best guess was that warning signals for the US economy would build through the course of 2019. I had been worrying that the fiscal stimulus was badly timed and would lead to overheating and potential recession in 2020. However, as Emiel suggested at the time, the risks seemed skewed towards a later downturn.

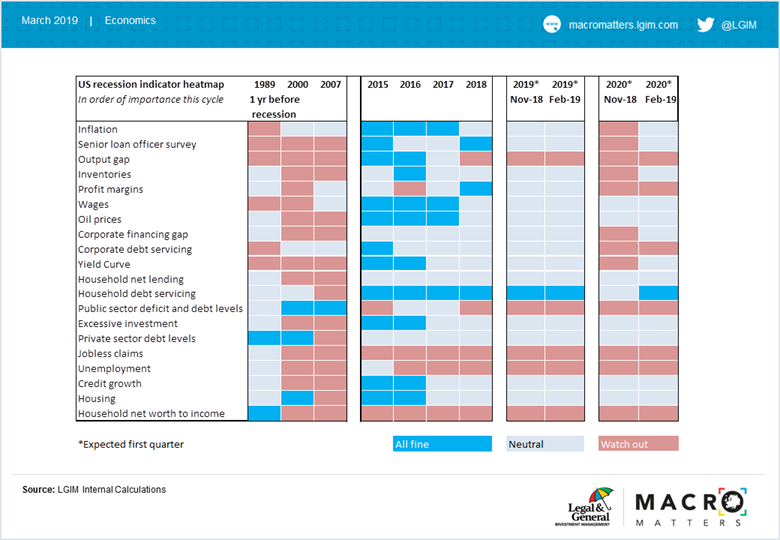

Now Emiel’s point appears increasingly prescient. Our updated recession indicators, while still a forecast, are looking more benign than I anticipated for the start of 2020. So what has changed? Surely the US economy is even more late cycle, with wages finally picking up?

The big shift has been the dovish pivot from the Federal Reserve (Fed). Rates are on hold earlier than I expected. It would be easy to blame the increased market volatility towards the end of last year, but we believe the primary reason is the softer inflation outlook, which in turn is driven by a number of factors.

Three reasons for a longer cycle

First, global growth has weakened with China disappointing. So imported price pressures are largely absent. While Erik is confident that China’s stimulus efforts will help growth stabilise, we are not expecting a significant rebound.

Second, US growth has slowed. Not disastrously, but enough to reduce the risk of the economy overheating. It appears that uncertainty around the trade war, the government shutdown and general Washington dysfunction have undermined business investment. In contrast, we view the terrible December retail sales data as an anomaly and continue to see the US consumer as an engine of growth.

Finally, inflation expectations have unexpectedly declined. This is crucial, as it will likely put downward pressure on price and wage setting behaviour. The Fed now appears willing to keep interest rates lower for longer in order to eventually generate a modest inflation 'overshoot' to help drag inflation expectations upwards. Indeed, the potential move to average inflation targeting represents a change in the Fed’s reaction function.

Recession clues

In terms of the twenty US recession indicators we track, the reduced risk of an inflation overshoot and the lower path for interest rates across the curve alleviates my concern that private debt-servicing costs will soon become more challenging. The cautious behaviour by companies (regarding capex for instance) is also helping to prevent the build up of excesses.

There now seems less risk of over-production and unprofitable investment leading to an inventory build or a rapid deterioration in the corporate financing gap. This in turn will probably make banks more willing in future to continue lending as their customers will not be experiencing as much financial stress.

To get a recession usually requires either rising inflation to force the Fed to slam on the brakes, a policy mistake, excesses in the private sector or the bursting of an asset price bubble. Despite the tight US labour market suggesting the economy is late cycle, none of these factors seem present today. There is always the risk of a large exogenous shock and while the recent news on the China - US trade war suggests at least a ceasefire, there is still the destabilising threat of tariffs on autos.

The US also has to deal with battles in Congress over the debt ceiling which are likely to coincide with a potential fiscal cliff in October if lawmakers fail to agree to lift the spending caps. But if major disruption can be avoided it seems likely the cycle will go on. Historically it has been difficult to engineer a US soft landing (returning growth to around potential, which we currently estimate at roughly 1½%), but as the fiscal stimulus fades in 2020 this is now becoming our baseline forecast.