February was a rough month in several corners of the US economy, but business cycle risk remains low overall when measured across a broad set of indicators on a trend basis. Yet a weak housing market and softer numbers for the manufacturing sector have raised worries that economic growth isn’t as strong as it appeared to be in previous months. Optimists argue that the recent slowdown is a temporary soft patch due to a harsh winter. That’s a plausible forecast, in part because the all-important labor market continued to post strong growth through February. As for the big picture, the overall macro trend still has a high degree of positive momentum, based on the current numbers.

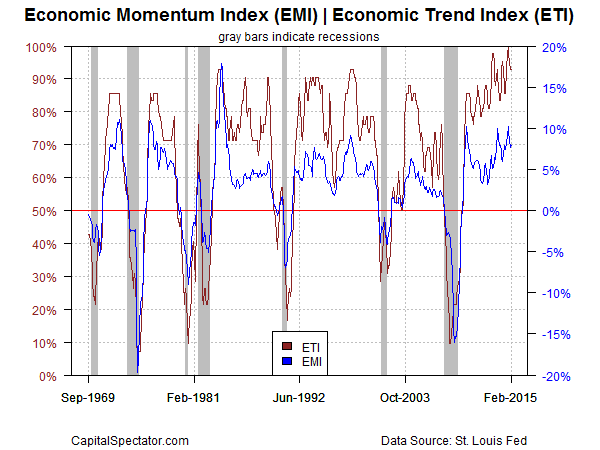

Using a methodology outlined in Nowcasting The Business Cycle: A Practical Guide For Spotting Business Cycle Peaks, economic and financial trends suggest that recession risk for the US remained low in Feburary. The Economic Trend and Momentum indices (ETI and EMI, respectively) continue to print at levels that equate with expansion. The current profile of published indicators through last month (12 of 14 data sets) for ETI and EMI reflect solidly positive trends.

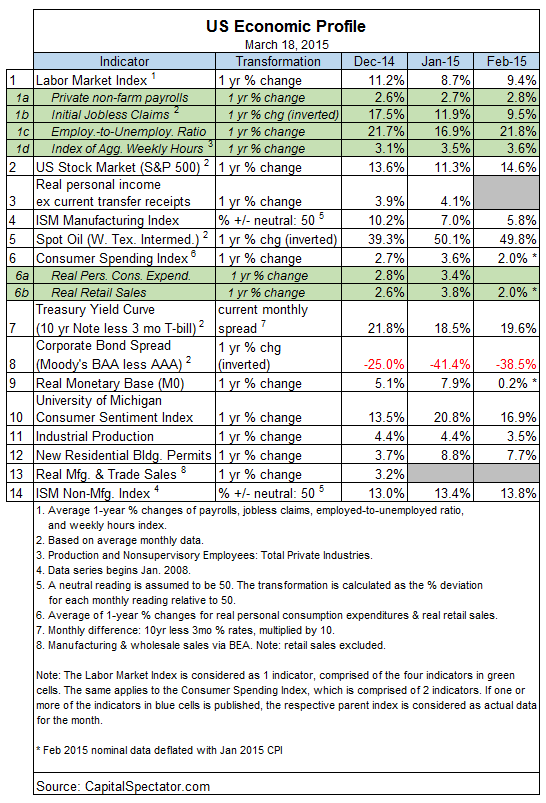

Here’s a summary of recent activity for the components in ETI and EMI:

Aggregating the data into business cycle indexes continues to reflect positive trends. The latest numbers for ETI and EMI indicate that both benchmarks are well above their respective danger zones: 50% for ETI and 0% for EMI. When the indexes fall below those tipping points, we’ll have clear warning signs that recession risk is elevated. Based on the latest updates for February — ETI is 92.9% and EMI is 7.9% — there’s still a sizable margin of safety between current values and the danger zones, as shown in the chart. (See note below for ETI/EMI design rules.)

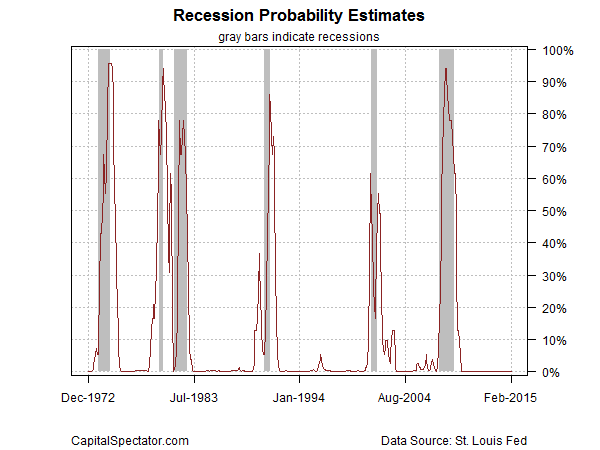

Translating ETI’s historical values into recession-risk probabilities via a probit model also suggests that business cycle risk remains low for the US. Analyzing the data with this methodology implies that the odds are virtually nil that the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) — the official arbiter of US business cycle dates — will declare last month as the start of a new recession.

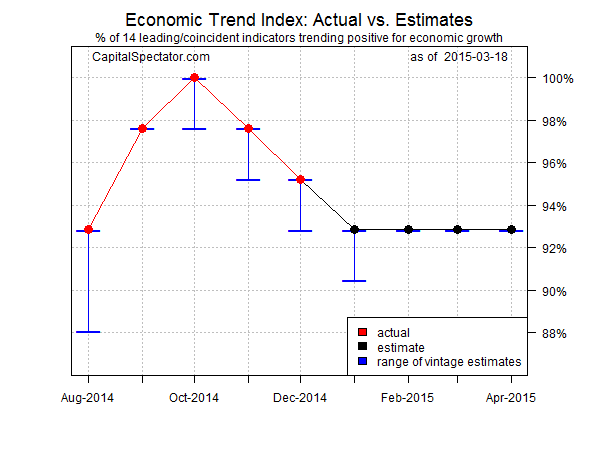

Let’s also consider how ETI’s values may evolve as new data is published. One way to estimate expected values for this index is with an econometric technique known as an autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model, based on calculations via the “forecast” package for R, a statistical software environment. The ARIMA model calculates the missing data points for each indicator, for each month through April 2015. (December 2014 is currently the latest month with a complete set of published data). Based on today’s projections, ETI is expected to remain well above its danger zone in the near term.

Forecasts are always suspect, of course, but recent projections of ETI for the near-term future have proven to be relatively reliable guesstimates vs. the full set of published numbers that followed. That’s not surprising, given the broadly diversified nature of ETI. Predicting individual components, by contrast, is prone to far more uncertainty in the short run. As such, the latest projections (the four black dots on the right in the chart above) offer support for optimism. The chart above also includes the range of vintage ETI projections published on these pages in previous months (blue bars), which you can compare with the complete monthly sets of actual data that followed, based on current numbers (red dots). The assumption here is that while any one forecast for a given indicator is likely to be wrong, the errors may cancel out to some degree by aggregating a broad set of predictions. Is that a reasonable assumption? Yes, according to the historical record for this forecast methodology. For additional perspective on judging the value of the forecasts via the historical record, here are the previous updates for the last three months: