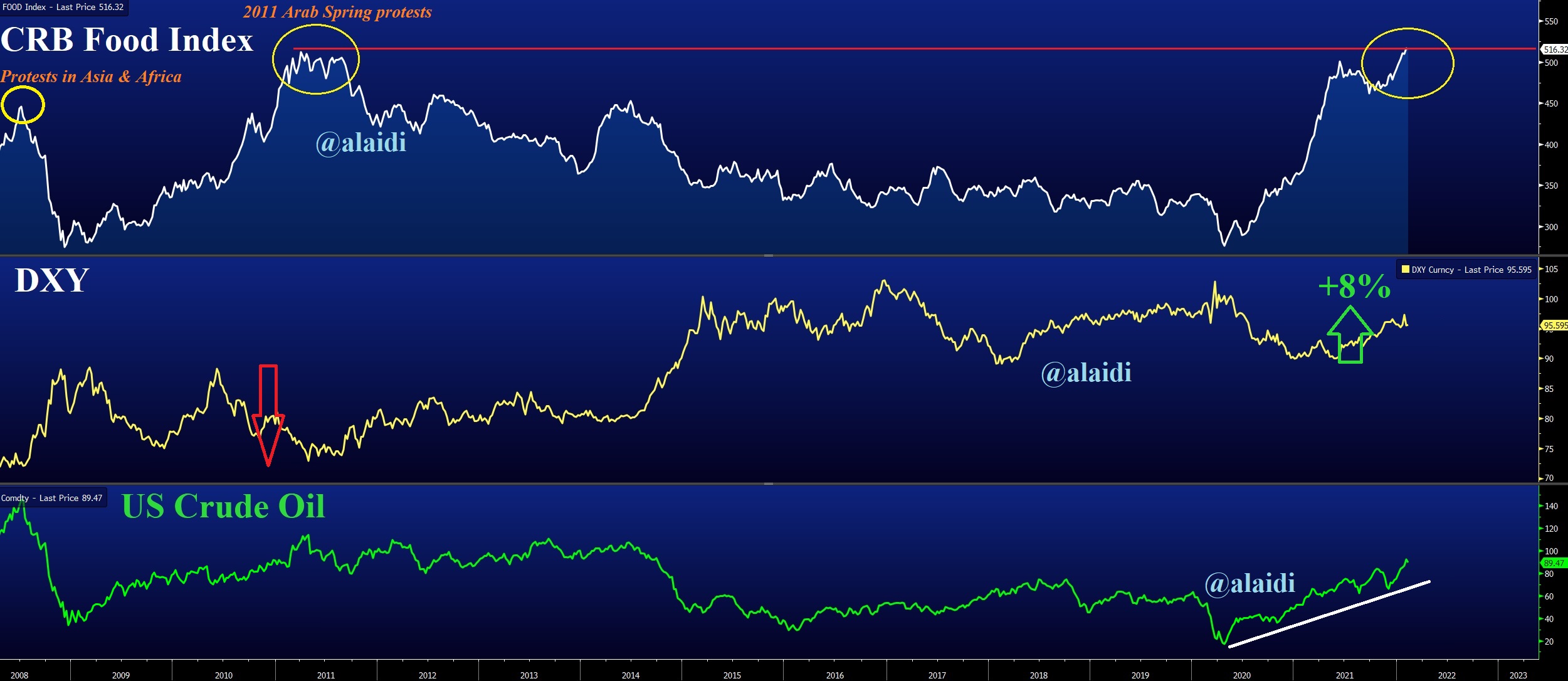

Most composite indices of food prices are pointing to multi-year highs, some even at new records. More specifically, the CRB's Food Index has just surpassed its previous high from March 2011.

The confluence of 8-year highs in energy prices and decade highs in wheat, soya and corn have undoubtedly contributed to the surge in foodstuffs. Yet, all this occurred despite a strengthening US dollar.

Would the surge in food prices have been higher, had the US dollar not strengthened 8% from last year's lows? For a perspective on how things could shape up ahead, let's look at past food crises below.

The 2008 record in food prices was a function of a commodity surpercycle, helped by biofuel food crises, a 40% tumble in USD and massive commodities purchases from China. The 2011 food price boom was also helped by a fresh commodities rally brought about by USD weakness and accelerating China demand for metals and energy.

WHAT HAPPENS NOW? Supply-driven pressures in energy and metals may subside, but unlikely to be reversed any time soon, owing to reduced investments and ongoing supply chain challenges.

WHAT IF if US dollar makes the transition from range-bound to outright decline due to catch-up tightening from the rest of the world and deficit obstacles to more Fed hikes. Could the food crisis be exacerbated by a weak USD?

We've definitely entered a new phase—where this is no longer about monetary policy normalization. It is about BoE's Bailey cautioning people against demanding wage hikes (he did say that), President Biden calming inflation nerves on primetime and even über dovish ECB's Lagarde finally opening the possibility for a 2022 rate hike.

Central bank tightening is surely here to stay. As long as policy errors from overtightening are avoided, food prices will not be stabilizing anytime soon; neither will the risk of unrest in developing nations and equity market volatility in the developed world.

Which stock should you buy in your very next trade?

With valuations skyrocketing in 2024, many investors are uneasy putting more money into stocks. Unsure where to invest next? Get access to our proven portfolios and discover high-potential opportunities.

In 2024 alone, ProPicks AI identified 2 stocks that surged over 150%, 4 additional stocks that leaped over 30%, and 3 more that climbed over 25%. That's an impressive track record.

With portfolios tailored for Dow stocks, S&P stocks, Tech stocks, and Mid Cap stocks, you can explore various wealth-building strategies.