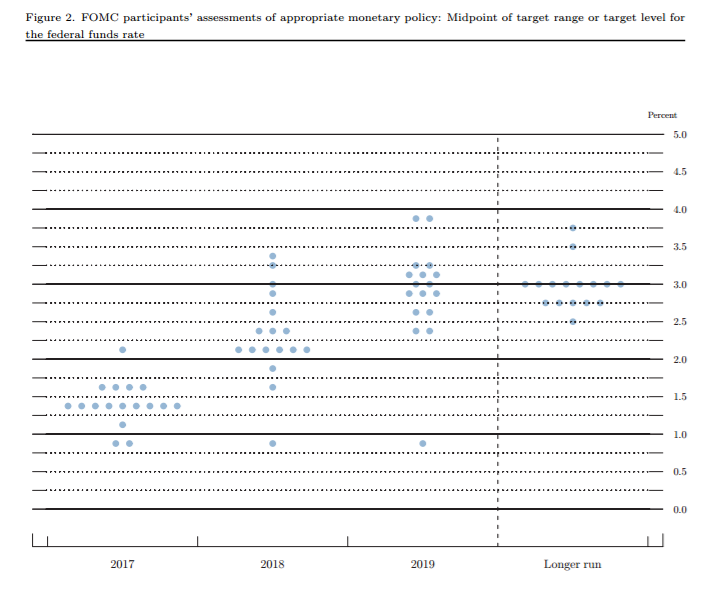

There is no doubt that the Federal Reserve is in the process of raising rates. The only question now is “when” and “how much.” The most recent “dot plot” from the latest Federal Reserve release provides some general projections:

Rates are currently in the .75-1% range while the plot projects they will most likely be 1.25%-1.5% by year-end, implying at least 2 more hikes. There is the additional issue of when the Fed will start to shrink its balance sheet. This past week, there were numerous Fed presidents speaking; some offered their opinions about the preceding two topics.

Cleveland Fed President Mester

Mester—who has been one of the leading Federal Reserve hawks for some time—argues that the Fed has achieved its full employment goal. She notes that not only is the unemployment rate low, but that, considering the declining labor force participation rate, the pace of job growth is adequate while the U6 underemployment rate continues to fall. As for the other half of the Fed’s dual mandate, prices should continue to move towards 2% in the medium term. She had this to say regarding the pace of increases:

Given my outlook, I don’t believe that removing accommodation calls for an increase in the fed funds rate at each meeting, but I do anticipate more than the one-increase-per-year seen in the past two years. In addition, I think that it’s important for the FOMC to remain very vigilant against falling behind as we continue to make progress on our goals, especially given the low level of interest rates and the large size of our balance sheet. We know that monetary policy affects the economy with long and variable lags, so policy actions have to be taken before our policy goals are fully met. If we delay too long in taking the next normalization step and then find ourselves in a situation where the labor market becomes unsustainably tight, price pressures become excessive, and we have to move rates up steeply, we could risk a recession. This is a bad outcome that disproportionately harms the more vulnerable parts of our society.

Mester makes a very important point. Some analysts have been critical of the Fed’s rate policy, usually arguing that sufficient labor market slack remains to warrant a continuation of low rates. But Mester counters that interest rates don’t have an immediate impact on the economy but instead act with a 12-18 month lag. If the Fed wants to keep the economy from over-heating, they need to act before all the policy pieces fall in place, requiring them to be action based on an incomplete set of facts.

Kansas Fed President George

Ultimately, George shares Mester’s conclusion that the Fed should continue to increase rates at a modest pace:

The economy continues to expand as sustained job growth and solid gains in household spending – the weak first quarter notwithstanding – are mutually reinforcing. The international backdrop poses less downside risks today, further supporting growth at home. In this environment, the role for monetary policy is to support the sustainability of the expansion. Therefore, as labor markets continue to tighten, continuing the gradual removal of monetary accommodation is the appropriate course for the FOMC.

Like Mester—and most other governors—George believes the Fed has accomplished its goals. While some labor market slack remains, the overall employment situation is sound and prices are approaching the Fed’s 2% target. Like Mester, George believes that waiting too long will cause damage. George adds two different supporting arguments. First, downside risks have dissipated. Therefore, a rate increase has a lower probability of hurting the economy. Second, after the Fed recently raised rates, there was no meaningful increase in the Kansas City Fed’s financial stress index, indicating the latest rate hike had no discernable impact on the financial markets. Had the opposite happened, the Fed would probably hold off on raising rates.

Boston Fed President Rosengren

Rosengren also believes the Fed has achieved its employment and inflation target. He views the weak 1Q number as a one-off, arguing late-in-the-quarter rising payrolls and income figures belie the weakness in the 1Q numbers. He also agrees with Mester and George that waiting too long will do more damage than good:

I will return to these topics in a moment, but let me share my overall view that it is important to avoid creating an over-hot economy (one that could require a less gradual monetary policy adjustment). And in order to avoid doing so, the Federal Reserve should continue gradually normalizing monetary policy.

Furthermore, he argued for a gradual reduction in the Fed’s balance sheet that should occurs “in the background”

In my view, that seems an appropriate point to consider beginning a very gradual normalization of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet. I believe the Fed should do so gradually, so that the reduction in the balance sheet is not disruptive, and so that it can occur largely in the background. This would maintain the Federal Reserve’s focus on the federal funds rate as the primary instrument of monetary policy.

The most logical policy to pursue is simply to let the portfolio run-off as bonds mature rather than reinvesting the principal payments.

The Fed’s overall tone is clearly more hawkish. Two hikes this year—barring unforeseen economic developments—are a given.