Are We or Aren’t We at Full Employment?

The changing nature of the US labor market continues to confuse analysts. Robert Waldmann at Angry Bear argues the low level of unemployment claims and high level of job openings indicates the labor market is tight. The low rate of unemployment, rising quits rate, and near six-year growth in establishment jobs supports this view.

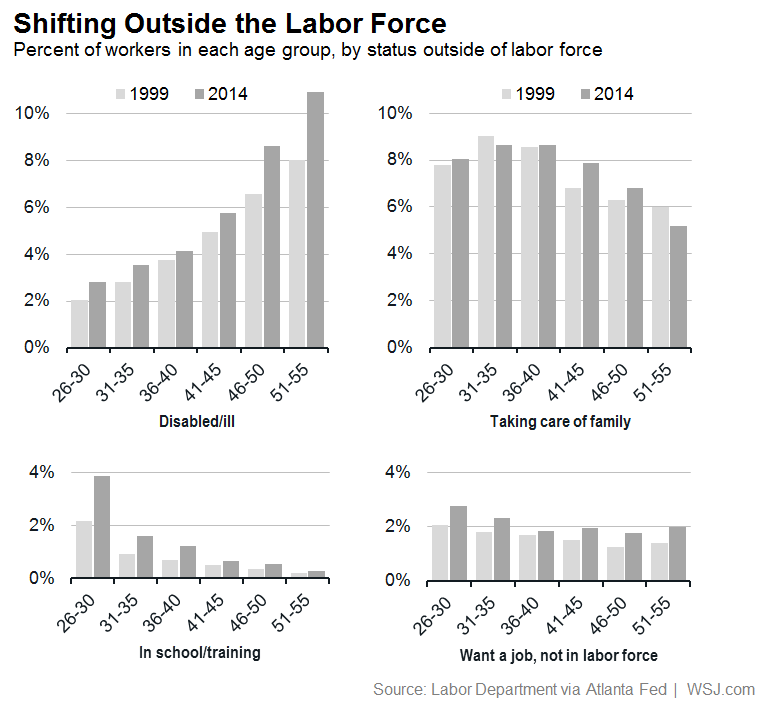

But the Wall Street Journal’s Real Time Economics Blog offered a more nuanced picture of the broader labor market, focusing on the composition of the 92 million people “not in the labor force.” After nothing the large increase in the number of younger people (aged 16-25) attending school and the number of older people (55+) who are retired, they turn their attention to the 25-55 aged group and find the following:

They offered the following explanation:

Many of these people aren’t working because they’re taking care of their families. Stay-at-home parents and homemakers and people caring for aging family members fall into this group. And as people age, an increasing number are disabled or ill. The most mysterious parts of the population are those who want a job and aren’t looking, and those who answer “other.” Among those who want a job and aren’t bothering to look, many are young. Very few Americans give some other reason for not being in the labor force.

Obviously, the above data leads to a discussion about the declining labor force participation rate, and, more specifically, whether or not the drop that’s occurred since the recession is permanent. Some is, largely due to retiring baby boomers. But, what would happen if the people attending school and taking care of family members saw a stronger job market? Would they leave academia and their family obligations to re-enter the labor force? There isn’t enough information for a definitive answer, but it’s worth considering.

The Fed Governors Speak

Two more Fed Governors gave conflicting signals this week. Governor Dudley stated it was too early to raise rates:

It is too early to consider an interest rate rise in the United States due to concerns about global economic growth, New York Federal Reserve Bank President William Dudley was quoted as saying by an Italian newspaper on Monday.

"The situation changed over the last few months," Dudley told CorrierEconomia last Thursday on the sidelines of a conference at the Brookings Institutions in Washington.

"It's true we thought we could raise interest rates by the end of 2015, but turbulence on financial markets, modest global growth, energy prices and macro-prudential imbalances are slowing this process down."

Like Governor Brainard, global issues appear to be driving his analysis. While he didn’t clarify his energy prices comment, it’s possible he shares the same concerns as ECB President Draghi about the possibility of extended oil price weakness potentially leading to deflation.

In contrast, San Francisco President Williams sees ample reason to raise rates soon and slowly:

The Federal Reserve is progressing toward its dual mandate of stable prices and maximum employment and should raise interest rates in the near future, said John Williams, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

"We always have to be looking through the front window” in setting monetary policy since it works on the economy with a lag, Williams said, speaking on Bloomberg Television with Michael McKee on Monday. "My own view is that the economy is still on a good trajectory.”

He also stated the Fed could cut rates is needed. Williams wants to prevent a situation where the Fed is chasing an increasing inflation rate; instead, he wants to begin the normalization process to prevent inflation from grabbing hold. Most economists side with Williams.

However, if research done by the San Francisco Fed is correct, Williams; proscription is completely wrong. In the latest economic letter, the SF Fed, using numbers from 1987-2015 determined the current natural rate of interest to be negative:

The Bond Market Yawns

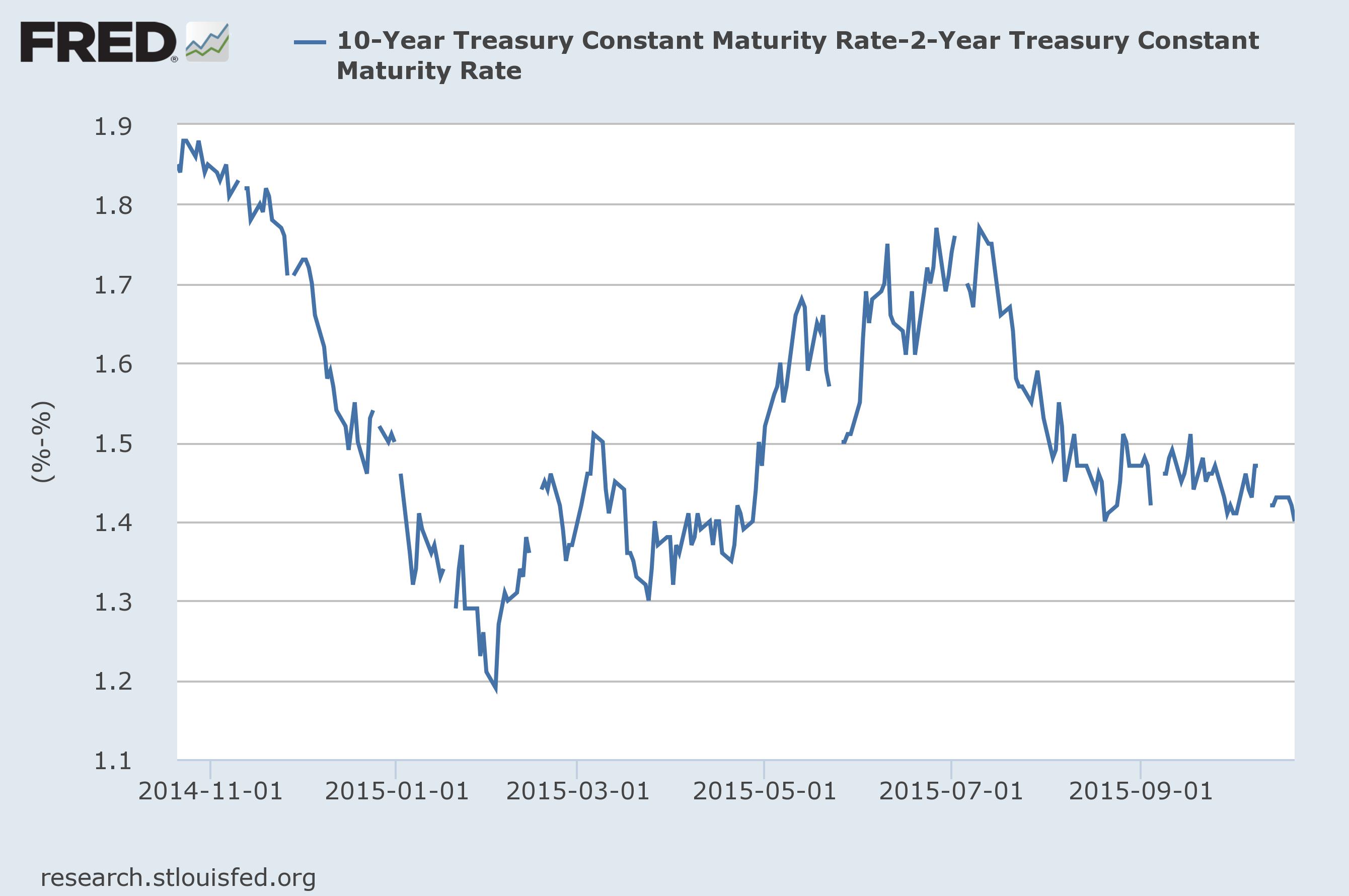

Last week, Bloomberg reported the Chinese government was selling large blocks of US bonds. That, and the Fed’s long-stated desire to raise rates by year end should potentially lead the market to sell-off in anticipation of higher rates. But the 30-2 and 10-2 spread remains remarkably constant:

Since the end of August, the 30-2 spread has traded between 220--230 basis points while the 10-2 spread fluctuated between 140--150 basis points. The long end clearly has second thoughts about the Fed’s potential tightening path.