Just a decade ago, Saudi Arabia maintained unequivocal power over oil prices.

As the largest producer in the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), it has the power to turn the spigot off and on during oil crashes and rebounds, essentially dictating the price of oil in the global market.

But it seems the Saudis are tiring of this role. And now, the United States is ready to take control…

Heavy Is the Head That Wears the Crown

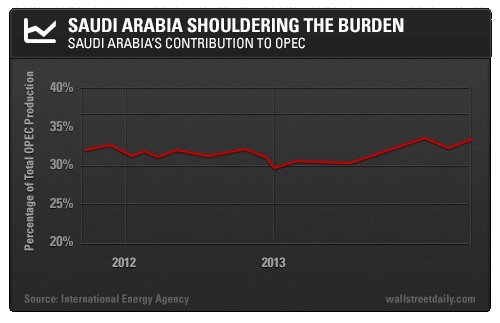

As the chart below shows, Saudi Arabia is still the dominant producer of oil within OPEC. It has the ability to produce more oil to temper prices or cut production to bolster prices.

Most recently, the Saudis used this power to flood the market and spark the oil crash, along with the other members of OPEC, in an effort to eliminate competition from the United States.

This ability to efficiently turn on or off production makes them the “swing producer.”

But the swing producer also tends to get the short end of the stick…

You see, if OPEC were to reduce output to keep prices high for everyone, they’d lose part of their market share to other, less-efficient producers who are not reducing production, but are still benefiting from the effect of higher prices.

The Saudis have been signaling for some time that they are fed up with the role…

Saudi Oil Minister Ali Al-Naimi expressed his country’s frustration with the situation in an exclusive interview with the Middle East Economic Survey earlier this year:

“Is it reasonable for a highly efficient producer to reduce output, while the producer of poor efficiency continues to produce? That is crooked logic. If I reduce, what happens to my market share? The price will go up, and the Russians, the Brazilians, [and] U.S. shale oil producers will take my share,” said Al-Naimi.

Saudi Arabia saw the rise of shale oil from the United States and realized that it would, once again, have to lose market share in order to stay profitable.

Thus, OPEC’s refusal to cut production and keep prices high is a clear message that Saudi Arabia is done with being the swing producer.

The Saudis are hoping that prices will stay low long enough that marginal shale producers go out of business, and that those strong enough to survive will take on the role of swing producer and cut production.

And what country has been gaining ground in the oil market lately? The United States, of course…

Long Live the New King?

While the shale revolution in the United States is in full swing, it’s still quite early in the game.

You see, U.S. oil production growth wasn’t expected to peak until the mid-2020s. And that might be pushed back a bit now, as the U.S. shale producers begin to temper exploration and production until prices recover.

However, it doesn’t change the fact that the United States has the ability to ramp up production, or as we are seeing today, delay or defer production (as a group) at the drop of a hat. And the number of producers is such that we can affect global supplies, and thus prices, almost as quickly as OPEC.

Yes, the United States is ready to assume the mantle of swing producers.

This realization is putting pressure on prices.

You see, many producers, like EOG Resources (NYSE:EOG) and Encana Corporation (NYSE:ECA), have announced lower capital spending going forward or the intention to keep production at the same level until prices recover – essentially keeping the spigot flow steady instead of turning it on full blast. But the world oil markets just aren’t buying it.

The reason is that there are now two entities that can turn on the oil spigot at a moment’s notice, and produce significant and measurable quantities of oil, should prices increase. Not to mention that without an increase in global demand, the price of oil isn’t going to stage a miracle recovery.

The Saudis and OPEC do have the ability to cut production (which many within the cartel are clamoring for) as does the United States.

But this time, the Saudis recognize that it’s in their best interest to wait this out and hope that enough shale production is cut back or that U.S. producers decide to permanently moderate production growth in return for higher prices. Barring a surge in global demand, this process could be protracted, and so could the slump in prices.