Key Points:

- U.S. worker productivity continues to decline.

- There are limits to GDP growth through debt.

- 3.00% economic growth unlikely to be reached in the near term.

The current American political cycle could be characterized by its bitter in-fighting and drive towards the partisan side of the fence. In particular, the debate over the U.S. economy appears to be another form of nationalism that both Republicans and Democrats use as a weapon in the war of words over which ideal is best for the economic growth of the nation. However, the truth is that neither party possesses a platform of sincerity and honesty and that without addressing the elephant in the room, productivity, we are unlikely to see a 3% GDP growth rate in anything other than our dreams.

The reality is that the current focus within Washington, as well as financial markets, has largely been centred on hikes to the Federal Funds Rate (FFR), as well as delivering a national budget with plenty of pork for the voters. It appears that both the White House and Congress are hell bent on again resorting to increases in debt to drive a `supposed’ economic recovery and real gains in both jobs and wages. In fact, Trump’s latest budget costing represents a sharp drive to the debt side of the equation and could almost be viewed as the republican version of fiscal stimulus.

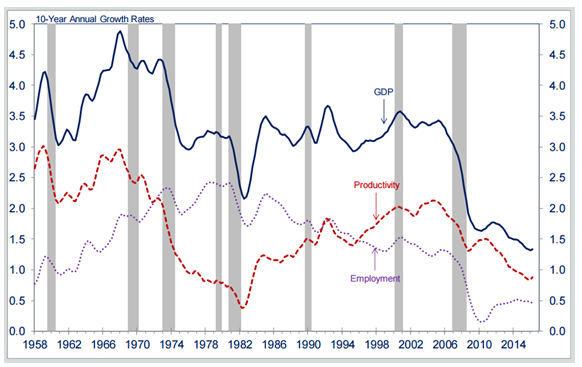

However, most economists universally accept that there are limits on how much increased government debt can fuel economic growth, which tends to play into the old adage that there are no free lunches. The reality is that increased monetary and fiscal stimulus has largely failed at producing the sort of GDP gains that the Whitehouse, and the American public, are seeking and that the cost/benefit of the packages are now seriously out of whack. Simply put, eight years of loose monetary policy and QE have had little impact on growth outcomes for America. Subsequently, it makes little sense to undertake the same activities, and expect a different outcome, without addressing the underlying weaknesses.

Most of the economic literature on growth seems to suggest that total factor productivity (TFP) is largely responsible for many of the economic success stories around the globe. In particular, Singapore has experienced huge gains in TFP over the past few decades and, as such, has experienced a wave of economic growth that is admirable. Much of the gains are largely from technological innovation that increases both national and worker productivity and results in a lean and competitive economy in global terms.

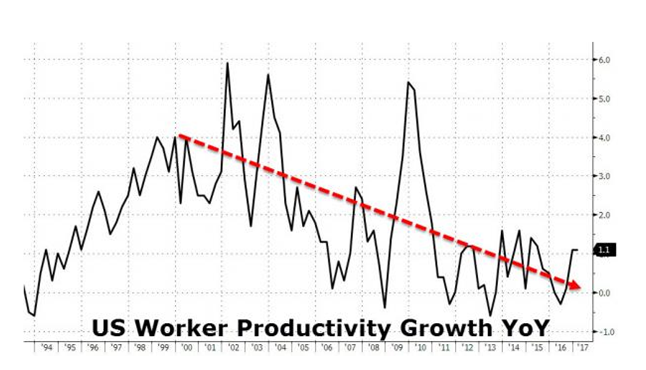

However, a cursory review of U.S. Worker Productivity Growth paints a bleak picture as the metric has clearly been within a downtrend over the past 17 years. Although fairly volatile, the indicator clearly demonstrates that the U.S. is losing ground yearly in a global economic battle on productivity and innovation and this certainly doesn’t bode well for GDP gains in the near term.

Subsequently, the time might finally have arrived where the political and economic leaders of the U.S. might have to actually address the ongoing slide in domestic worker productivity lest American industries continue to lose their competitiveness in the global market. However, instead of debating the underlying limitation of Keynesian stimulus, or incentivising corporate investment and innovation, Washington instead retreats to political partisanship and ideology.

Largely, the reason for the avoidance of any real debate on the issue is that fact that a technological revolution is coming within the Western world that threatens to cause significant structural unemployment. Machines and technology are poised to revolutionise some sectors and I think many of us can already see the changes with the advent of automatic checkouts at the super market, or online ordering at McDonalds. These innovations are certainly starting to have an impact in the lower skilled worker categories and will continue to do so over the next decade. So now is the time for the U.S. government to start the process of transition in training and upskilling employees to work in different industries with increased worker productivity. However, this requires significant political will and leadership in a time when Washington lacks both.

Ultimately, the reality is that the U.S. is unlikely to see the sort of economic growth they are hoping for whilst there are continuing drags on the domestic economy from poor productivity and increased global trade competition. In addition, a too low for too long monetary policy has reduced the incentive for a drive towards innovation and has, instead, promoted growth through increases in corporate and personal debt. Subsequently, don’t expect the 3.00% growth target to be reached any time soon unless all of these underlying problems are recognised and fixed.