Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, aka AOC, recently railed against the President when he threatened Colombia with tariffs if they should refuse to accept their citizens being deported back to them. In her typical hyperventilated fashion, she implored us to “remember” that “WE pay the tariffs, not Colombia.”

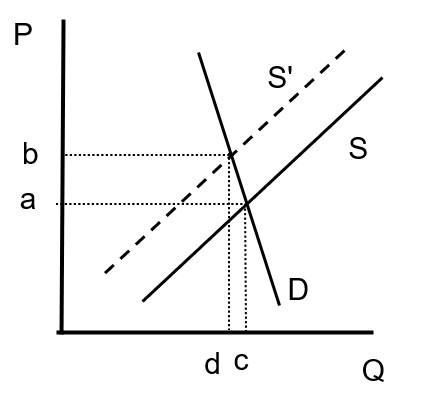

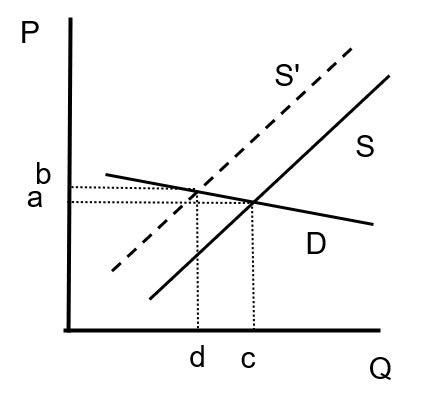

For a change, AOC is not entirely wrong but merely mostly wrong. She seems to remember at least one important thing from Econ 101 and that is that businesses don’t pay anything to anyone, since a business is just a legal structure. Shareholders, other stakeholders, consumers, or suppliers pay and/or receive the cost of goods sold, taxes, wages, and so on. Unfortunately, I don’t think that was her point and she missed the important bit which is that ‘who pays the tariff’ depends almost entirely on the elasticity of demand for the product. Here are two charts. In each case, the tariff shifts the supply curve leftward/upward by the amount of the tariff, the same amount in both pictures. In each picture, the quantity consumed of the good being tariffed goes from c to d and the price goes from a to b as the market moves from one equilibrium to the other.

The first chart shows an inelastic demand curve, which is characterized by the fact that large changes in price do not change the quantity demanded very much. In this case, the main effect is that consumers buy almost as much of the good, but the price moves almost the full amount of the tariff. Consumers end up paying most of the tariff.

The second chart shows an elastic demand curve, in which even small changes in price induce large changes in the quantity demanded. In this case, the main effect is that consumers buy much less of the more-expensive good, and the price goes up only a little so that the seller bears most of the cost of the tariff.

Thus a blanket statement that “we pay the tariffs” is wrong. It is sensitive to the characteristics of the product market. One needs to be very careful about how we define the product market because it matters. I would argue that the elasticity of the demand for coffee is quite low, which is why Starbucks (NASDAQ:SBUX) even exists. If the demand for coffee was very elastic, charging $5 a cup for bad coffee would not produce a line around the block at rush hour. But that is not what we are talking about here. The question here is, what is the demand elasticity for Columbian coffee? The answer to that question is very different. Coffee as a way to wake up in the morning has few close substitutes. But Columbian coffee has many, very very very close substitutes. My favorite right now is Ethiopian Yirgacheffe coffee. I also like a good Panama Boquete. Add 20% to the cost of the Boquete, and I think I’ll mostly drink the Yirgacheffe. Add 20% to both of them, and I’ll go to Brazilian Santos, or Columbian, or Kona.

I think the reaction of the Columbian President tells you everything you need to know about what he perceives about the demand for Columbian coffee and therefore the impact a tariff would have on exports of Columbian coffee to the United States. Trump very quickly got what he wanted with his Trump Tactical Targeted Tariffs (TTTT™). So to review: +1 for TTTT, -1 for AOC.

A couple of other points about tariffs and tariff strategy.

First, this episode illustrates a very important distinction to be made between the use of targeted tariffs and the use of blanket tariffs. Blanket tariffs, for example on everything we import from a major trading partner or on every trading partner, definitely increase prices for consumers. How much, and which prices, depends on how easily domestic untariffed supply can substitute for the imported supply. But the answer is certainly that prices go up. But let me point you to two articles I’ve written previously about this:

Tariffs Don’t Hurt Domestic Growth, August 28, 2019. This is a really good piece. In summary, tariffs are bad for global growth but they are not the unalloyed negative you learned about in school. How good/bad they are for growth depends on whether you are a net importer or a net exporter, and how large the Ex-Im sector is in your country. Truly free trade works in a non-theoretical world only if “(a) all of the participants are roughly equal in total capability or (b) the dominant participant is willing to concede its dominant position in order to enrich the whole system, rather than using that dominant position to secure its preferred slices for itself.” Really, you should read this.

The Re-Onshoring Trend and the Long-Term Impact on Core Goods, February 22, 2022. This is not directly about tariffs, but the broad imposition of tariffs (if they happen) should be thought of as reinforcing this prior trend. The prior trend, of re-onshoring production to the US, has been under way for several years – the way that COVID exposed long supply lines certainly helped the trend but the long-term globalization trend was already reversing and in this article I argue that this means core goods inflation going forward is likely to be small positive, rather than persistently in deflation. In the context of the current discussion, President Trump has certainly made re-onshoring of production a major goal of his Administration. So whether it happens because of TTTT, or because of blanket tariffs, or because of tax breaks given for domestic production, the direction of the inflation arrow is clear.

I’m not worried about hyperinflation from tariffs and I think that if you’re the biggest and the strongest economic actor they’re probably more good than bad for domestic economic outcomes.

Reality is more nuanced than we learned in school. Not everything that expands the economy is good, and not everything that is good expands the economy. Not everything that is bad causes inflation to go up, and not everything that causes inflation to go up is bad.