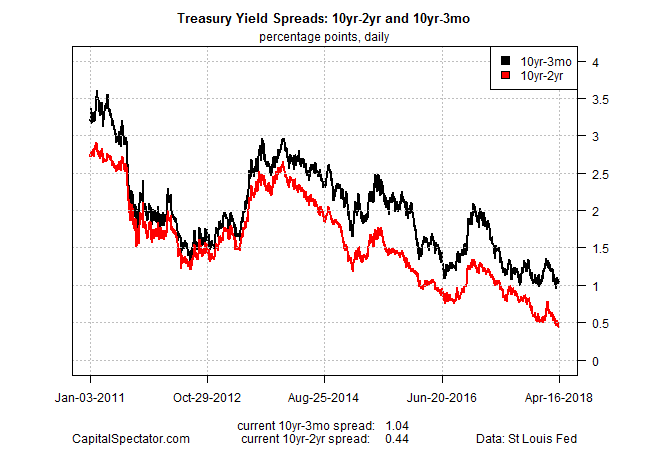

The difference between the 10-year and 2-year Treasury rates narrowed to 47 basis points on Monday (April 16) – the smallest gap since late-2007. The last time this widely followed spread was this close to zero the US economy was close to a recession. Is this indicator flashing a similar warning today? No, according to a broad reading of the economic data, which reflects a healthy trend. The question is whether the narrowing yield spread is still a reliable late-cycle warning that the macro profile will weaken in the months ahead?

Recent comments by Federal Reserve officials have cast doubt on the validity of the yield curve’s credentials for predicting a new recession. Last month, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell said that the historically reliable record of yield-curve warnings for the economy no longer applies. Cleveland Federal Reserve President Loretta Mester echoed his skeptical comments on the yield-curve signal.

But some economists are reluctant to dismiss the narrowing rate spread as an irrelevant artifact of business cycles past. For example, Lars Christensen of Markets and Money Advisory last week posed the question: “Will Jay Powell murder the expansion in 2020?” He explained that “I am presently more worried about the Fed causing a recession – likely in 2020-21 – than by a sudden spike in inflation.”

Worrying about recessions that far in advance is the equivalent of guessing. Nonetheless, with the yield curve in shooting distance of inverting – short rates rising above long rates – it’s becoming harder to ignore the subject.

The arguments in favor of shelving the yield curve’s warning this time around include the explanation that an extraordinary level of foreign demand is depressing the 10-year yield and so the dependability of the signal for the US economy has been compromised for business-cycle analysis. The opposing view is that the crowd always claims that “it’s different this time” during late-cycle yield-curve warnings and the results aren’t pretty.

The reality is that there’s plenty of risk on both sides of this debate. Looking for a new recession without sufficient support in a broad profile of economic indicators tends to lead investors to make portfolio decisions they regret. The narrowing yield curve may be genuine warning sign this time, but it’s still too early to go off the deep end with this interpretation.

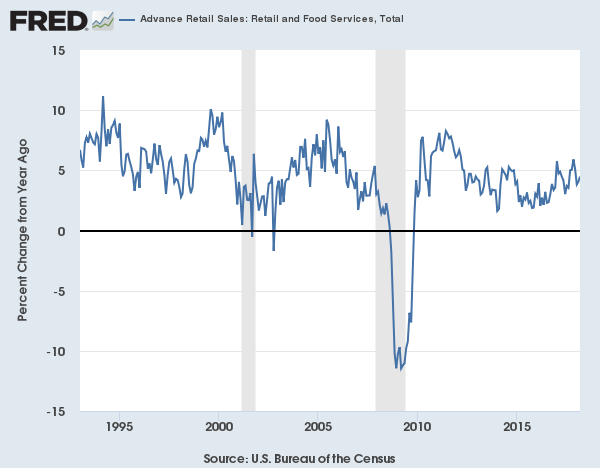

Consider, for instance, yesterday’s update on retail sales for March. The year-over-year trend for headline spending ticked up to a moderate 4.5% pace. This could be the last hurrah, but it might point to an expansion with room to run.

Pessimists are quick to note that yesterday’s estimate of first-quarter GDP growth via the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow model dipped to a weak 1.9% — a worrisome decline from the 2.9% advance in last year’s Q4.

The counterargument is that the economy has weakened in Q1 in recent years only to bounce back later on and so this pattern may be repeating in 2018. Meantime, optimists can still point to the New York Fed’s latest Q1 GDP nowcast, which is relatively upbeat via a 2.8% estimate for the government’s upcoming report on economic output for the first three months of this year.

For all the back and forth about the yield curve these days, and what it means (or doesn’t mean) for the economy, the same set of caveats and solutions still apply. First, it’s risky to expect one indicator to provide a timely and reliable signal for estimating recession risk in real time now and forever. Any one dataset is vulnerable to failure from time to time.

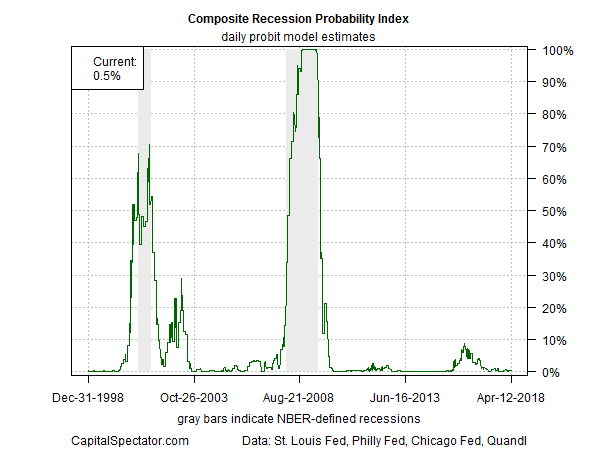

That leads to the next best thing: monitoring a broad set of numbers to monitor the business cycle. By that standard, the macro trend remains healthy, as this late-March update shows.

Economic profiles can turn stale quickly, however, particularly when the cycle is turning. The solution for this challenge is crunching a broad set of numbers frequently to capture early signs of regime shift – the mandate for the US Business Cycle Risk Report. But on this score the latest update continues to show no sign that a new downturn is imminent. As reported in Friday’s edition of the newsletter, the probability was virtually nil that an NBER-defined recession had started, based on data published through April 12.

The obvious caveat: the upbeat assessment for the US macro trend is subject to change, and a change could unfold quickly. That’s hardly an excuse to assume facts not in evidence by cherry pick indicators to rationalize a particular outlook, but it is a reason to run the numbers often.

Whenever the next recession begins, the tell-tale signs will almost certainly arrive after the fact. The challenge is reliably identifying the turning point with the shortest time gap from the point of no return to the date when the signal shows up in the reported numbers in a clear and meaningful degree.

Disclosure: Originally published at Saxo Bank TradingFloor.com