The collective wisdom of the bond market for much of this year has been betting that interest rates would soon peak and fall. But those bets appear to be unwinding in the wake of Wednesday’s Federal Reserve meeting and press conference.

Exhibit A is the rise in the 2-year and 10-year Treasury yields, which are widely followed as key maturities for economic and financial markets analytics. On those fronts, the crowd is reassessing its recent view that rate cuts are on the near-term horizon.

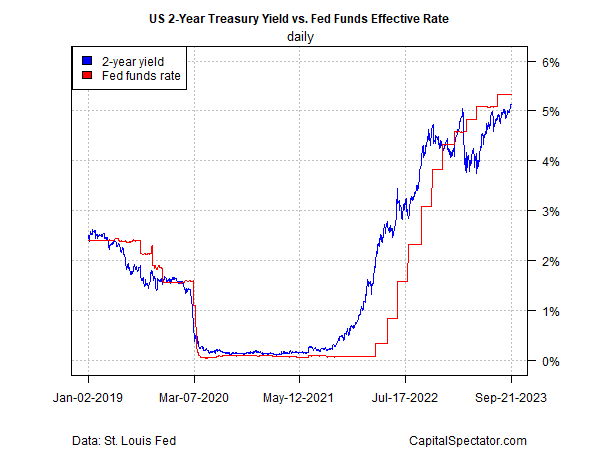

Let’s start with the 2-year Treasury yield, which is considered a proxy for market expectations on Fed policy. For much of this year, the 2-year yield has traded below the effective Fed funds rate, which implies that the market expects the central bank’s rate hike will peak and perhaps reverse. But that view appears to be fading as the 2-year yield moves closer to the current 5.25%-to-5.50% Fed funds rate range.

The 10-year yield is pushing higher again too. In yesterday’s trading (Sep. 21), the benchmark rate rose to 4.49%, the highest since 2007.

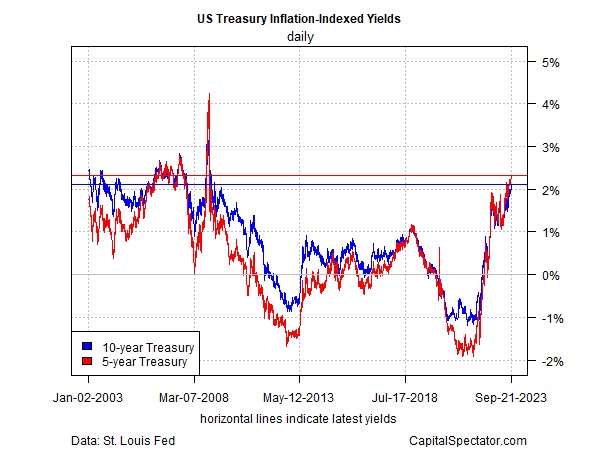

Inflation-indexed Treasury yields continue to push higher, too, testing the 2%-plus real range.

One of the catalysts that’s reportedly behind the latest run of higher Treasury yields is Fed Chair Powell’s hawkish comments on Wednesday on the matter of real (inflation-adjusted) interest rates.

“It’s a real rate that will matter, and that needs to be sufficiently restrictive,” he advised, although exactly what level defines “restrictive” was left unsaid. “I would say you know it’s sufficiently restrictive only when you see it,” he added. “It’s not something you can arrive at with confidence in a model or in various estimates.”

By some accounts, the Fed appears to be on a path to leave rates higher for longer. Fed rate hikes may be over, or perhaps there’s one more in the pipeline, but rate cuts are expected to come later than recently expected.

As The Wall Street Journal reports:

“The fact that we’ve come this far lets us really proceed carefully,” said Powell. He used those words—“proceed carefully”—six times during Wednesday’s news conference, a sign of heightened caution about lifting rates.

“He didn’t sound to me like he was itching to hike again,” said Michael Feroli, chief U.S. economist at JPMorgan Chase, who thinks the Fed’s July rate rise will be its last for the current cycle. “For Powell, he sounds like he’s pretty comfortable where they are, sitting back, and watching things play out,” Feroli said.

The new dot plots for the Fed – the FOMC participant's expectations for the Fed funds rate – support the case for a higher for longer outlook. The FT notes:

The median estimate of the Fed’s 19 policymakers is for the bank’s benchmark rate to fall to just 5 per cent to 5.25 per cent next year. That was significantly higher than the 4.5 per cent to 4.75 per cent they signaled when the dot plot was last updated in June. By 2026, it was still forecast to be between 2.75 per cent and 3 per cent.

“What they’re saying there is if you have stronger growth for this year and next, it increases the risk that core inflation does not descend as much as they hope and expect,” said Daleep Singh, an ex-New York Fed official who is now chief global economist at PGIM Fixed Income.

“Therefore there is a potential need to keep nominal interest rates somewhat higher than they previously forecast,” he added.

The good news for investors is that the highest yields in ~15 years, either real or nominal, can be locked in with a buy-and-hold strategy. No one knows if current rates are at or near a peak, but this much is clear: the case for a relatively higher allocation to Treasuries vs. recent history hasn’t looked this compelling since George W. Bush was walking the floor in the Oval Office.