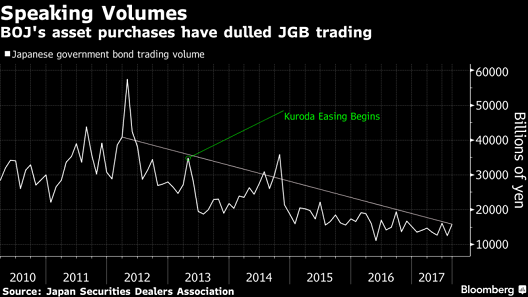

On Tuesday, market watchers did not witness the buying or selling of a single 10-year Japanese Government Bond (JGB) on an exchange. Not one.

Let that sink in for a moment. The Bank of Japan has swallowed up so much of the country’s debt obligations in its quantitative easing endeavors, trading activity across the entire JGB space has become “razor thin.”

Theoretically, the circumstances could present liquidity risk. The bid-ask spread for JGBs could widen to such an extent that investors could struggle to sell at a “market price.”

Who would consider buying in a market where you might not be able to sell? (Or short-sell in a market where you could not buy back in.)

In reality, the Bank of Japan would alleviate the liquidity issue by becoming the buyer of first, second, third and last resort. And it may have to do so. Panicky sellers could appear, fearful that the Bank of Japan will be forced into a less accommodating phase due to tightening by the Federal Reserve and tapering by the European Central Bank.

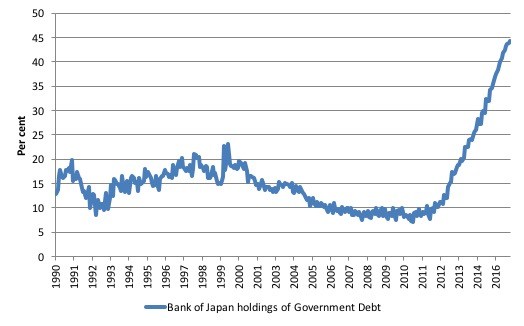

Bear in mind, the Bank of Japan already owns roughly 45% of the Japanese government bonds in existence. That number is likely to hit 60% by the end of 2018.

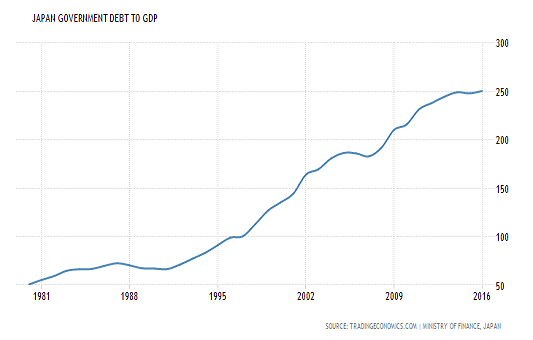

Will Japan eventually gobble up all of its country’s government bonds? Unfortunately, the Japanese government spends gobs of money that it does not have. Nor will the country ever receive enough in tax revenue to finance its spending needs, including the repayment of debts and any interest.

So what does the Japanese government decide? It issues new obligations at 0.1% interest and spurs its central bank, the Bank of Japan, to buy the new debts at ridiculously high prices and non-existent yields. (Nobody outside of Japan covets “IOUs” of questionable quality that yield nothing. They might as well hold cash.)

At 250% debt-to-GDP, though, 0% 10-year yields via “yield curve control” may always be necessary to continue servicing debt obligations as well as to stimulate economic growth. Permanently.

It follows that the Bank of Japan will never consider meaningful rate increases let alone “normalization.” On the contrary. It will continue to manipulate rates lower, electronically printing yen forevermore.

Indeed, the Bank of Japan has made it clear that it would buy an unlimited quantity of 10-year JGBs to keep the yield at 0%. This implies that it would create an unlimited supply of electronic yen credits.

Weakening the currency is one thing. It may even help the export-dependent nation in the short-term. The possibility of a currency crisis is quite another.

Since the Bank of Japan is well on its way to acquiring 80%, 90% or the entire load of JGBs, the Japanese government and its central bank may intend to cancel its national debt outright. They could wipe the slate clean and try to convince the world that a default did not occur.

Create all of that money out of thin air? With no adverse consequences?

More likely, volatility in forex (foreign exchange) trading would go ballistic. It is even conceivable that the viability of the yen as we know it gets called to the currency carpet. It simply would not end well.

Perpetual quantitative and qualitative easing (QQE) to deal with structural budget deficits and moribund economic prospects is a mechanism for kicking the Sapporo can as far out into the future as possible. Japan’s leadership prefers this path over perceived austerity.

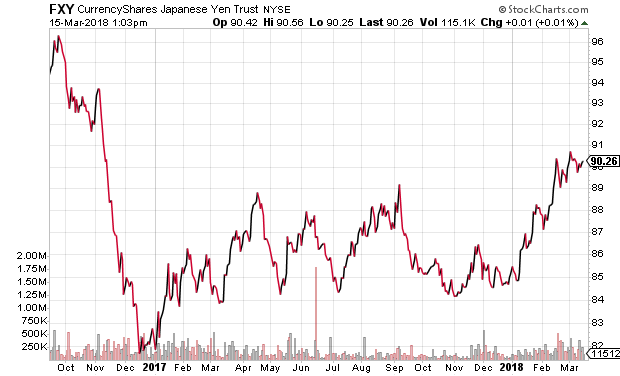

Granted, in the near term, weakening a currency may benefit exports and fostering a wealth effect may prop up assets (e.g., stocks, real estate, etc.). And it is true that, since September of 2016, when Japan announced it would implement “yield curve control” to keep 10-year JGBs near 0%, the yen is weaker across most major currencies.

Note: CurrencyShares Yen Trust (NYSE:FXY) has picked up significant ground against the US dollar in 2018.

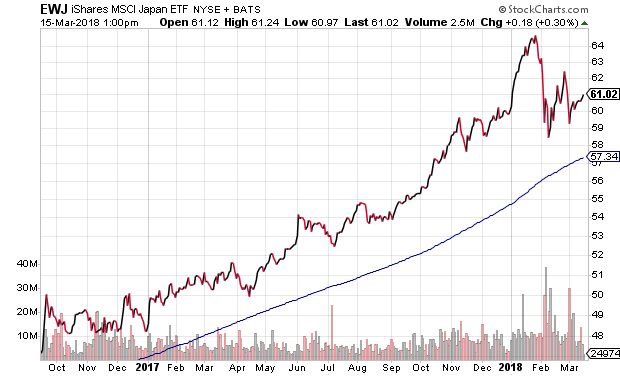

It is also worth noting that since September of 2016, Japanese stocks have been rocketing higher. And they’ve done so largely on the heels of monetary stimulus as opposed to fiscal stimulus, like the US tax cuts.

Why discuss Japan’s quagmire here in March of 2018? When so many financial authorities believe Japan’s economy has been showing signs of improvement? Primarily because you can’t go anywhere without hearing about Trump’s tariffs and the probability of a trade war.

Imposing a tariff, or a tax on imports, typically occurs when one country is looking to level a playing field or gain a competitive advantage. The fear is that other countries will retaliate with tariffs of their own. And, before you know it, a global trade war causes panic clear across world financial markets.

In the same vein, if the Bank of Japan does not cooperate with the prevailing winds in global central banking, other countries may view its endless yen creation as a way to gain an unfair competitive advantage in goods exporting. If you’re an Asian neighbor like China or South Korea, you might further depreciate your currency to compete with Japan. Meanwhile, the US already expresses dissatisfaction with currency manipulation by other countries to gain advantages in trade. Similar to trade war concerns, a global currency war could cause hysteria in world financial markets.

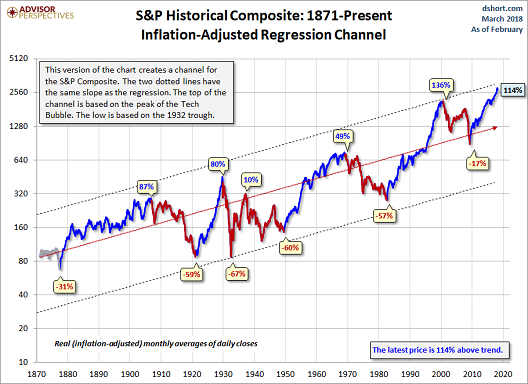

Neither an actual trade war nor a definitive currency war is necessary for a bearish stock sell-off. Fear of tariffs, taxes and currency manipulation, all in the name of “balanced trade,” could spark a self-reinforcing downtrend.

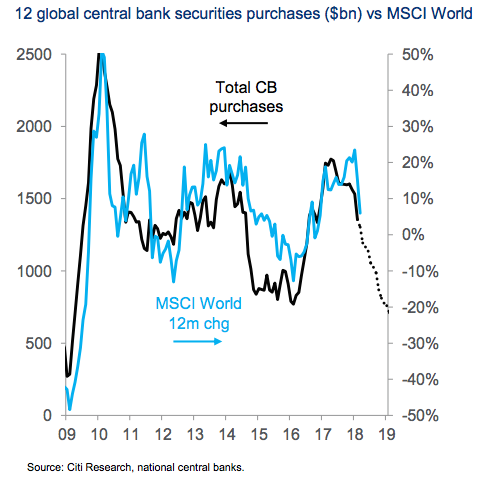

On the flip side, the global central bank “put” has been backstopping world markets since the Great Recession ended. Investors have been conditioned to buy each and every pullback on the belief that central banks will coordinate their efforts and collectively ride to the rescue.

Yet there’s a possibility that the Bank of Japan refuses to go along with the European Central Bank and the US Federal Reserve on tapering/tightening at some point this year. If policy differences become more pronounced as 2018 goes forward, confidence in globally coordinated central banking could get battered. Severely overvalued stock markets could be left without their nine-year safety net.

If you’ve let your stock allocation exceed your target, or if the siren song bullish momentum has made you exceedingly greedy, consider rebalancing some of your dollars into ultra-short bonds. PIMCO Enhanced Short Maturity Active Exchange-Traded (NYSE:MINT) is closing in on a 2% yield holding investment grade and government debt with an average maturity of about 7 months.

Disclosure Statement: ETF Expert is a web log (“blog”) that makes the world of ETFs easier to understand. Gary Gordon, MS, CFP is the president of Pacific Park Financial, Inc., a Registered Investment Adviser with the SEC. Gary Gordon, Pacific Park Financial, Inc., and/or its clients may hold positions in the ETFs, mutual funds, and/or any investment asset mentioned above. The commentary does not constitute individualized investment advice. The opinions offered herein are not personalized recommendations to buy, sell or hold securities. At times, issuers of exchange-traded products compensate Pacific Park Financial, Inc. or its subsidiaries for advertising at the ETF Expert website. ETF Expert content is created independently of any advertising relationship.