Few metals have as controversial a supply side as tin. Cobalt also springs to mind, largely due to the relative importance of the Democratic Republic of Congo as a supply source. But tin likewise seems to come from areas prone to military unrest, where illegal mining of the ore provides an opportunity to fund said unrest.

Even in established producing countries like Indonesia, supply is hampered by extensive illegal mining, and the authorities have been engaged in a long running struggle to control illegal mining, principally to avoid environmental damage that occurs at unregulated mines.

Tin has benefitted from a broader commodity rebound this year. Prices are rising and LME inventory is falling as demand from the electronics industry, particularly in China, remains solid. However, one of the key supply-side variables is Myanmar, China’s new source of supply.

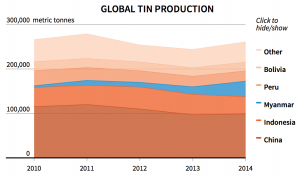

As the graph below from Thomson Reuters shows, Myanmar is the only significant global source that has been on the rise in recent years. All others by and large have remained static or fallen.

Source: Thomson Reuters

Indonesia has the potential to export more concentrate. Its drive to control illegal mining and encourage greater domestic value-added refining has limited export volumes in recent years, encouraging China to increase imports from neighbouring Myanmar.

Reuters reports that almost all Chinese tin ore and concentrate imports now come from Myanmar, following the 2013 discovery of high grade reserves at Man Maw in northeast Myanmar. Annual production is now estimated at about 33,000 tons of tin concentrate, which Reuters reports is more than 10% of the metal’s global output.

Governments and corporations have largely turned a blind eye to the fact that the mine is controlled by the United Wa State Army, the strongest of the myriad armed groups that have kept Myanmar in a state of near-perpetual civil war for decades. Companies sub-contract supply chain auditing to third parties like Conflict Free Sourcing Initiative (CFSI), but many see this as sidestepping their ethical sourcing responsibilities.

CFSI is an Africa-focused organisation without the resources to investigate Asian supply chains effectively. Major Chinese refiners such as Yunnan Tin make no secret of the fact that they buy Myanmar-sourced concentrate extensively (up to a third of Yunnan’s tins is said to come from the country, and much of that will be from Man Maw). This metal then finds its way into Apple phones, as well as thousands of other electronic devices, jewellery and chemical pastes.

The extent to which the sourcing of tin from what is widely regarded as a conflict zone possesses a future hazard remains to be seen. But costs are rising as mining in Man Maw moves underground, and output may fall. Combined with both short- and medium-term projections of rising demand, this could be supportive of higher tin prices this year and next.

Tin consumers should monitor the news on Myanmar’s tin supply. If a solution to territorial independence could be reached with the United Wa State Army that controls mining in the remote Wa territory, external investment could rise, and volumes could increase and prices could fall. However, all previous attempts have failed. It is just as likely supply chain concerns are acknowledged by western firms and efforts brought to bear on Chinese smelters to limit imports in which case prices could rise. Few metals are as beholden on one region as a swing producer as tin is on Myanmar.

by Stuart Burns