Last week I was in beautiful Argentina with a diverse team of investors and mining executives, including my good friend Frank Giustra; Ian Telfer, founder of Silver Wheaton (NYSE:SLW) and current Chairman of the Board of Goldcorp (NYSE:GG), which has sizeable investments in Argentina; and Serafino Iacono, Chairman of the Board of Pacific Exploration and Production (TO:PEN) (formerly Pacific Rubiales), which is active throughout South America. Together we toured various natural gas and crude oil mining projects in Tierra del Fuego, Mendoza and Santa Cruz, where we had the opportunity to speak with Governor Alicia Kirchner, elder sister to former Argentinian president Néstor Kirchner.

One of the highlights of the trip was meeting with current president Mauricio Macri in Buenos Aires. Macri, as you might know, was elected in late 2015 on his credentials as a businessman and former mayor of Buenos Aires. His administration ends more than a decade of socialist rule by Kirchner and his wife Cristina Fernández, who was indicted this past December on corruption charges.

Even with Macri at the helm, corruption remains a problem in Argentina. The South American country currently ranks 95th in Transparency International’s 2016 Corruption Perceptions Index.

But economic conditions are improving. After contracting 1 percent in 2016, country GDP is expected to grow as much as 2.8 percent this year.

Macri’s mission to make Argentina great again has already led him to abolish currency controls, return to world credit markets, attract foreign investors and set in motion a plan to reduce the fiscal deficit. After that, he hopes to get around to tax reform. In the meantime, there’s the energy sector.

A Plan to End Natural Gas Imports by 2022

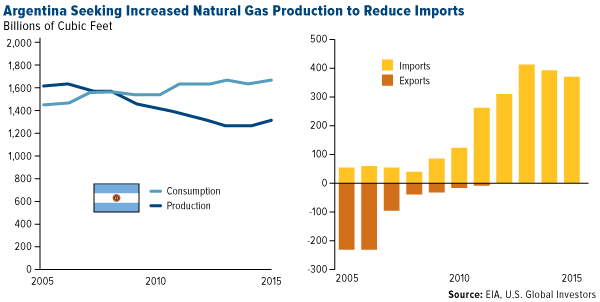

Since 2008, Argentina has been a net importer of hydrocarbons, mainly natural gas, which represents more than half of the country’s energy matrix. Prices are low right now, so the economic impact is not detrimental. Should prices begin to rise substantially, however, it could destroy the economy. As such, my friends and colleagues were invited to help develop the fields and prevent further overreliance on imports. The government, in fact, wants to end them altogether by 2022.

Production declined mainly because of underinvestment during the two Kirchner administrations. Stringent regulations forced companies to sell product in the domestic market at a discount to international prices. Capital dried up to reinvest in the fields, and the natural decline of well production drove the overall output down. Making matters worse, companies lacked access to capital markets due to the Argentina sovereign debt default in 2001.

As I said, the country is fabulously rich in hydrocarbons such as natural gas and petroleum. It’s estimated to have the world’s third-largest natural gas reserves and, according to the independent research Wilson Center, it “could possibly be the country with the most promising shale prospects outside of the United States.” Its most promising formation is Vaca Muerta (“Dead Cow”), located in the Neuquén basin, which has been compared to Texas’ prolific Eagle Ford play in terms of depth and thickness.

YPF (NYSE:YPF), the government’s oil company, has already done exceptional exploration work, so there are numerous areas ready to be developed. This is the opportunity for us.

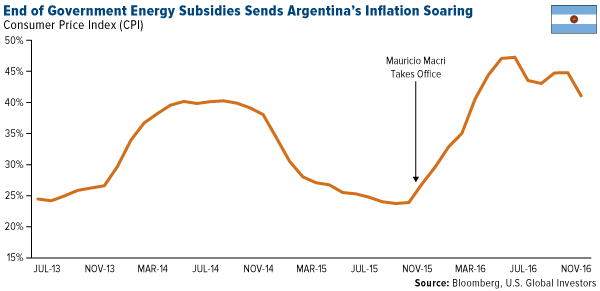

Having seen the projects firsthand and spoken to policymakers, I’m confident Macri can help open up Argentina’s energy sector and streamline production. Upon taking office, one of the president’s first acts was to slash the previous administration’s energy subsidies, which cost the government more than $51 billion over the past 13 years. Electricity bills in Buenos Aires rose a reported 500 percent as a result, but the move allowed the government to save a much-needed $4 billion in 2016 alone.

Policy Change in the U.S. Has Also Had Amazing Consequences

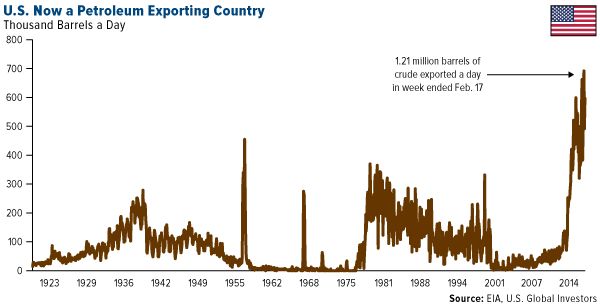

As for the U.S. energy sector, crude exports have never been stronger. After Congress lifted the U.S. oil export ban in December 2015, exporters didn’t hesitate to turn on the spigots. Now, for the second week as of February 17, the U.S. sent more than 1 million barrels of crude onto world markets, filling the gap created by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) in December when it agreed to trim production.

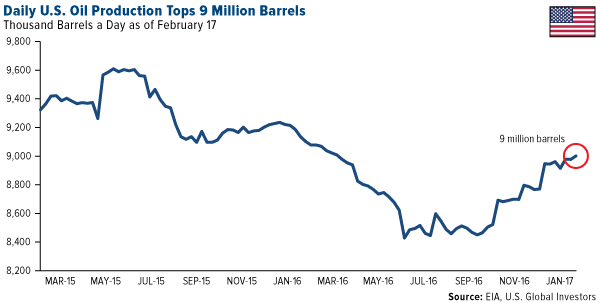

Producers are also ramping up activity. In the week ended February 17, companies pumped more than 9 million barrels a day for the first time since April 2016. The recent weekly record of 9.6 million barrels a day, set in July 2015, could be tested if producers continue their upward trend.

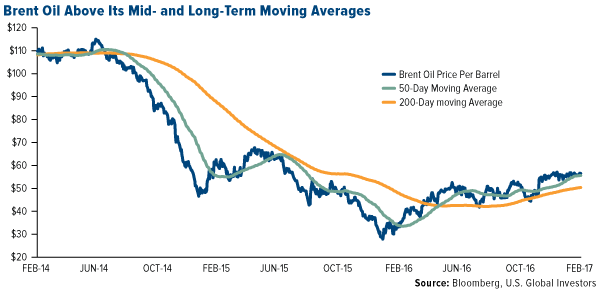

Even with increased output, prices continue to creep up. From its low of just over $30 a barrel last February, Brent crude has climbed 88 percent.

Happy investing!

Disclosure: All opinions expressed and data provided are subject to change without notice. Some of these opinions may not be appropriate to every investor. This commentary should not be considered a solicitation or offering of any investment product. Certain materials in this commentary may contain dated information. The information provided was current at the time of publication.