AI is popular. Emerging market bonds, needless to say, are not.

Which is perfect for us responsible contrarians striving to retire on dividends. The more neglected an asset, the better.

But what’s the catalyst for these big yields? I’m talking dividends between 6.5% and 12.1%, by the way.

That’s easy. When the buck gets banged up, these funds soar. And that is exactly what is playing out today.

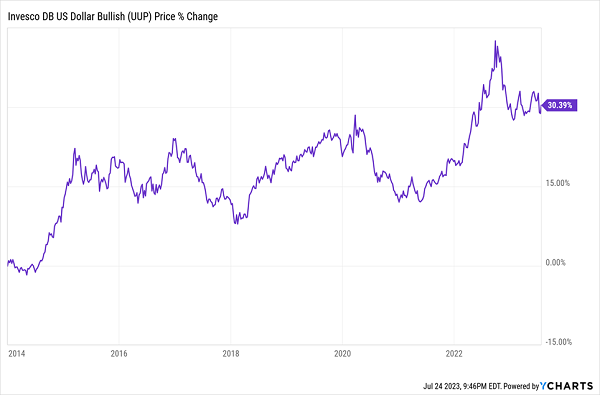

The US dollar has been en fuego for the past decade. I know, it’s hard to believe given the noise from the “demise of the dollar” crowd. But these guys have lost a lot of money betting against the buck.

Why the rally in the Greenback? Lots of reasons: the strength of the U.S. economy, relative economic weakness in other parts of the world, and the dollar’s status as a safe-haven protection against the unknown.

A Divine Decade for the Dollar

But it’s increasingly looking likely that the U.S. dollar has peaked, at least on a medium-term basis. The Federal Reserve has signaled, for now, at least a pause in its interest-rate hikes. On the horizon—a horizon that keeps moving out of analysts’ crosshairs, mind you—a recession might be brewing. And inflation, while marginally higher last month, has spent a full year in retreat.

In other words: The dollar should continue easing in the months ahead. And that is going to light a fire under emerging-market bonds (EMBs).

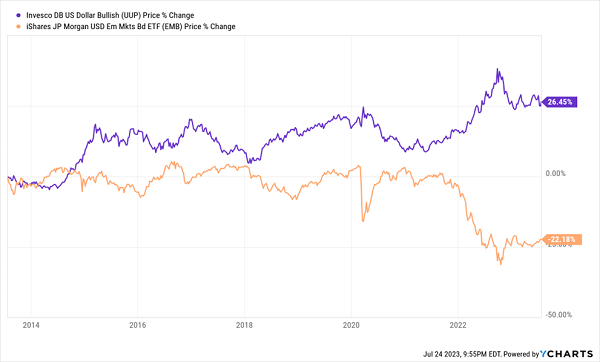

A weak buck is a big catalyst for EMBs. Foreign countries and companies often borrow in U.S. dollars rather than their own currency—but they still have to service the debt in their own currency, or buy U.S. dollars to do it, and a burlier U.S. dollar makes that more difficult. Thus, EMBs typically suffer when the dollar is rising, which is why it’s best to buy EMBs when the dollar is heading flat to lower.

A Strong Inverse Relationship Between the Dollar and Emerging-Market Bonds

So, if the time to buy is now, what should we be buying?

As always, with debt, look to closed-end funds (CEFs), which can turbocharge both the upside opportunity and the potential yields. Right now, a few EMB-focused CEFs yield as much as 12.1%.

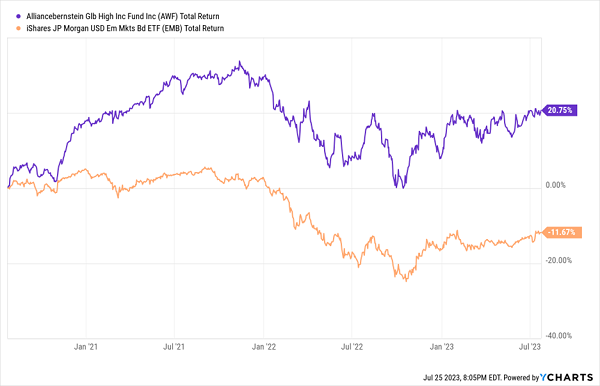

One way to stick a toe into EMBs is with a global fund—a CEF that invests around the world, so emerging-market bonds are part of the platter, but not the whole enchilada. The AllianceBernstein (NYSE:AB) Global High Income Fund (AWF, 7.9% distribution rate) does just that while throwing off a fat yield of nearly 8%.

Director Paul DeNoon—who helmed AWF to “Best Fund Over 10 Years” standing with Lipper between 2012 through 2015—invests in everything from U.S. Treasuries to South African bonds to mortgage-backed securities. He mostly sticks to higher-rated junk debt; below-investment-grade corporates make up more than three-quarters of the fund right now. EMBs are currently a small portion of the portfolio, though Paul might very well increase his exposure if the opportunity seems ripe.

When it came time for us to sell out of emerging-market debt, we held on to AWF. That’s largely because Paul is a flexible manager. When EMBs make sense, he uses them. If not, he has other weapons in his arsenal.

Thanks, Paul!

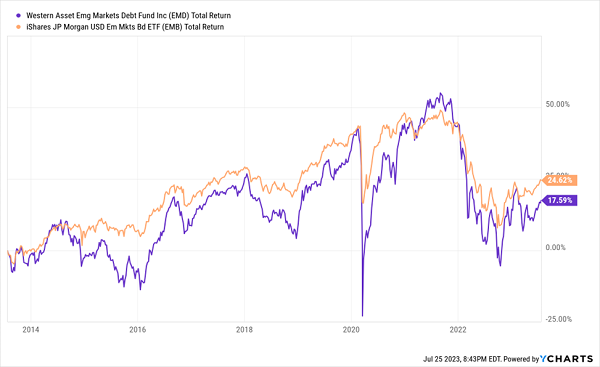

A more direct way to invest in EMBs is the Western Asset Emerging Markets Debt (NYSE:EMD) (EMD, 9.5% distribution rate), which features not only a high yield of nearly 10%, but also monthly distributions.

EMD is a broad, diversified basket of emerging-market debt that’s almost entirely invested in U.S. dollar-denominated bonds. It spreads its investments across sovereign (45%), corporate (30%) and quasi-sovereign (14%) bonds, with a sprinkling of local-currency-debt and other investments.

Credit quality largely straddles the junk line, with 37% in BBB debt, and 30% in BB debt. And geographically speaking, there’s little concentration worry here. EMD invests in dozens of countries, with Mexico the largest exposure at just 9%; Indonesia (5%), Brazil (5%) and Oman (4%) are among other highly represented nations.

Despite a pretty high use of leverage, at 28%, EMD isn’t an overly volatile fund.

But It’s Not Terribly Productive, Either

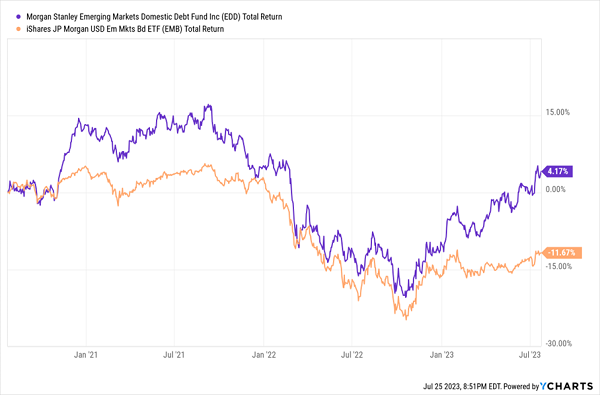

You might switch tactics and consider the Morgan Stanley (NYSE:MS) Emerging Markets Domestic Debt Fund (EDD, 6.5% distribution rate).

Like EMD, EDD offers a broad swath of emerging-market debt across the world, but it does so in primarily non-U.S.-denominated bonds. Risks are somewhat similar—a strong dollar can harm these bonds—but the pain is typically felt at the extremes. That is, rampant global inflation can weigh on local-debt EMBs, as can deep, extended recessions.

Comparatively, though, EDD has held up quite well compared to its USD-denominated brethren. Moderate use of leverage (13%) helps keep volatility muted, too.

EDD Isn’t Nearly So Jet Lagged

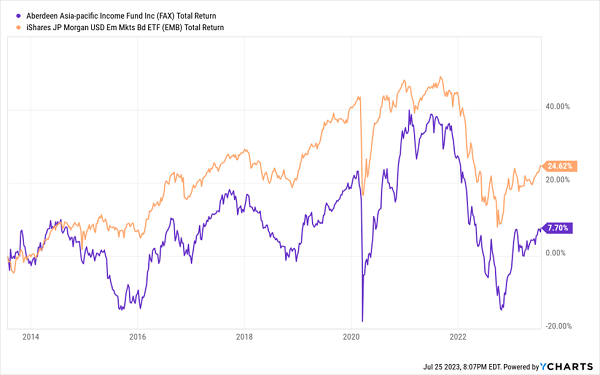

The abrdn Asia-Pacific Income Fund (FAX, 12.1% distribution rate) is a specific bet on emerging-market debt, and one with a mouth-watering yield—paid monthly—to boot!

FAX invests in EM sovereign, quasi-sovereign and corporate debt from Asian and Pacific countries such as India, Indonesia and China. It also leans most heavily on BBB-rated bonds, sticking largely to the investment-grade side of the bond rating scale.

Asia-Pacific’s biggest strength—a heaping helping of debt leverage, at 32% currently—is also its biggest drawback. When EMBs are in vogue, we’ve used FAX to turbo-charge returns in the space. But it plummets hard when they fall out of favor.

It’s OK to Own FAX, But Only When the Time Is Right

Disclosure: Brett Owens and Michael Foster are contrarian income investors who look for undervalued stocks/funds across the U.S. markets. Click here to learn how to profit from their strategies in the latest report, "7 Great Dividend Growth Stocks for a Secure Retirement."