Academic financial quantitative analysis began in earnest in the 1970's as a response to the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH). EMH proponent believed that you can't beat the market with stock picking because everything about a stock is already known by the market.

As a test of EMH, researchers began to scour the CRSP tapes of stock prices and found "anomalies". They found that you could beat the market with well diversified portfolios of small cap stocks, stocks with low P/B, low P/E and so on. Thus quantitative analysis was born.

Today, we have gone well beyond the early days of anomalies literature. Now technical analysts have embraced quant techniques with gusto, Most of what technical quant research have been in the form of, "What did the market do when X happened?"

Among many others, leaders of this form of analysis include Ryan Detrick, his former employer Schaeffers Research, and Rob Hanna at Quantifiable Edges.

Yet, there are many pitfalls to quantitative technical analysis, as the fundamental quants have learned through many decades of painful experience.

The Zweig Breadth Thrust: A case study

Consider the following example as a case study: Last Thursday, the market flashed a Zweig Breadth Thrust buy signal, which I wrote about (see Bingo! We have a buy signal!) and a number of other technical analysts comment on as well.

What was curious was the differing interpretation of the implications of this signal. Tom McClellan classified the returns of past ZBT signals and came to a lukewarm conclusion:

Signal type Quantity

Great! 11

Meh… 4

Horrible 12I am one of the biggest believers in the world about the idea of stock market breadth being one of the best tools we have to indicate financial market liquidity. But based on this evidence, I cannot offer much in the way of optimistic commentary about this current ZBT signal, especially since it has occurred at a point that appears to be the early stage of a new downtrend. Robust rallies within downtrends are great opportunities to get ready for the next phase of the downtrend. The problem is that they often disguise themselves that way, when in reality a new uptrend is beginning after a long bear market. This current moment does not seem like the end of a long bear market just yet.

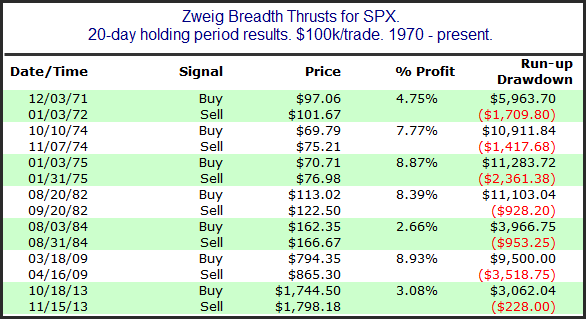

By contrast, Quantifiable Edges had an unabashed bullish take on ZBT signals since 1970:

What's going on? How can two different analysts looking at the same data come up with such vastly different conclusions?

What's the theory behind the signal?

What I will try to do in these pages is to take apart the ZBT signal and identify the differences of interpretation.

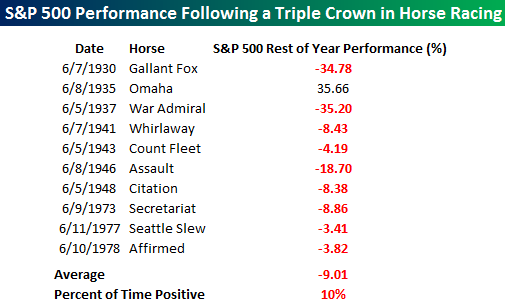

First and foremost, what I learned as a quant is to make sure that there is an economic rationale behind a market factor or signal. Consider the following market signal uncovered by Bespoke, which has had an incredible success rate and has been performing quite well this year. But would you really put money on it? (Recall that American Pharoah won the Triple Crown this year).

First lesson: There are spurious correlations everywhere.

In the case of the ZBT, we are betting on breadth and momentum. There is a set of well established academic literature that momentum works, both fundamentally (estimate revision, earnings surprise) and price momentum.

There are a number of nuances to positive breadth and, more importantly, price momentum. Sure, price momentum in stock picking gets you better returns, but the downside volatility can rip your face off. Just ask recent holders of biotech stocks. I call that approach Momentum 1.0.

Here is Momentum 2.0. Researchers at Cass Business School found a better way of approaching price momentum (paper here). Stock level price momentum works much better when the market is going up. Avoid betting on price momentum when the market is falling. I found a similar effect when picking sectors and industries in my own work (link here).

In the case ZBTs, they are powerful bull moves in a very short time, which leaves the market highly overbought. With such an overbought market, should you continue to bet on positive breadth and price momentum?

That`s the next lesson: Really understand what you are betting on.

Don't torture the data until it talks

Quants fall into the trap of "torturing the data until it talks" all the time in their research. If X doesn't give you the results that you want, tweaked the parameters slightly one way, or second or third way until you do. Such an approach can lead to a convoluted set of rules like the Hindenburg Omen (see The hidden message of the Hindenburg Omen).

While researchers can take steps to minimize the backtesting problem of data torture, users of the research don't have that luxury. However, research users can try to understand what a model is really telling them by perturbing the rules to see how the results vary. In the case of the ZBT, we are further hampered by the low number of observations. There are very few instances of ZBTs, so it is equally important to dive into the data to really understand what it is telling us.

In that regard, several points come to mind in the differing viewpoints on ZBT return results. Tom McClellan's analysis, he cited four signals since 2008.

If you look closely, the 2011 signal is missing from Rob Hanna's table. Both the 2011 and 2013 signals are also missing from my own analysis, which is based on Stockcharts.com data. This is a classic case of perturbing the data. Rather than point fingers to say who is right or wrong, data and signal variations can be explained a number of different ways:

- Differences in data feeds: I have noticed that Stockcharts.com TRIN readings can differ slightly from NYSE published TRIN. This may be caused by a difference in data feeds, e.g. NYSE vs. consolidated tape.

- Differences in calculation techniques: One of the sources of possible model readings could come from the way the weighting technique used in the calculation of the Exponential Moving Average, or EMA.

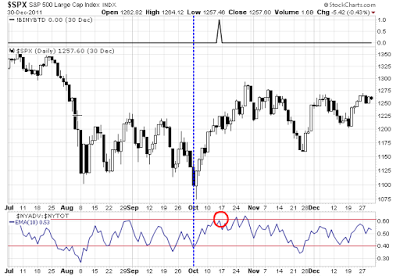

What's even more puzzling is that Stockcharts.com has its own ZBT flag and its readings appear to be inconsistent with the observed readings derived from their own EMA calculations. Consider this chart of the most recent signal. Note how the ZBT flag (top panel) went negative as a setup signal, followed by the buy signal shortly afterwards. This can be confirmed by the EMA moving below 0.40 and rising above 0.615 in the bottom panel.

Now look at the 2011 "signal", or non-signal: There was no negative setup signal in the ZBT flag in the top panel, but it did flash a buy signal afterwards. However, the bottom panel indicates that EMA did not actually exceed 0.615, though it got close.

It`s the same story with the 2013 "signal", or non-signal. The ZBT flag (top panel) did not flash a negative value to signal a setup, though it did show a buy signal shortly after. The EMA (bottom panel) did not reach 0.615 when the ZBT flag showed the buy signal.

Another observation I found from Tom McClellan's analysis is that most of the poor performance of ZBT occurred in the 1930's and before the Second World War. Using McClellan's own classifications, ZBT would have had this record in the post-war period:

Signal type Quantity

Great! 9

Meh… 3

Horrible 1

Conclusion: ZBT = BuyWhat can we conclude from examining the data? Perturbing the data can yield different ZBT signals, Even discounting the different versions of the ZBT buy signals, I think that everyone can conclude that we saw a bona fide ZBT buy signal last week.

The question then becomes one of what subsequent returns were and how much can we rely on ZBT to take action in our portfolios. My conclusion, which agrees with Rob Hanna, is that the stock market tends to rise after ZBT buy signals. At worse, stocks didn't go up, so a long position really doesn't hurt you very much. The poor ZBT returns from the 1930's represent a market environment from a long-ago era that may not be applicable today and therefore those results should be discounted.

Even McClellan's observation of the single bad return in the post-War period isn't that bad:

Bottom line: ZBT = Buy the market.

For my last word to quants everywhere: Learn to apply a critical eye and common sense sanity checks to your analysis. Read the Financial Modelers' Manifesto and always remember The Modelers' Hippocratic Oath:

~ I will remember that I didn't make the world, and it doesn't satisfy my equations.

~ Though I will use models boldly to estimate value, I will not be overly impressed by mathematics.

~ I will never sacrifice reality for elegance without explaining why I have done so.

~ Nor will I give the people who use my model false comfort about its accuracy. Instead, I will make explicit its assumptions and oversights.

~ I understand that my work may have enormous effects on society and the economy, many of them beyond my comprehension.

Notice

If you are interested in subscribing to content like this when Humble Student of the Markets becomes a subscription site, please register your email address at the poll here to receive an early bird discount. Further details on the transition, pricing, etc. can be found here. The poll will be open until midnight, Sunday October 11, 2015 (Pacific Time).

Cam Hui is a portfolio manager at Qwest Investment Fund Management Ltd. (""Qwest""). This article is prepared by Mr. Hui as an outside business activity. As such, Qwest does not review or approve materials presented herein. The opinions and any recommendations expressed in this blog are those of the author and do not reflect the opinions or recommendations of Qwest.

None of the information or opinions expressed in this blog constitutes a solicitation for the purchase or sale of any security or other instrument. Nothing in this article constitutes investment advice and any recommendations that may be contained herein have not been based upon a consideration of the investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs of any specific recipient. Any purchase or sale activity in any securities or other instrument should be based upon your own analysis and conclusions. Past performance is not indicative of future results. Either Qwest or Mr. Hui may hold or control long or short positions in the securities or instruments mentioned.