What’s at stake: Productivity growth fell sharply following the global financial crisis and has remained sluggish since, inducing many to talk of a “productivity puzzle”. In the US, we may be seeing what look like early signs of a reversal. We review recent contributions on this theme.

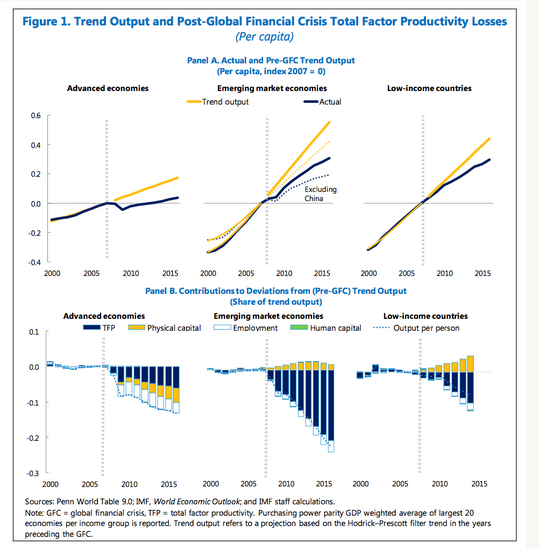

A recent IMF note finds that the productivity slowdown reflects both crisis legacies and structural headwinds. In advanced economies, the global financial crisis has led to “productivity hysteresis” — persistent productivity losses from a seemingly temporary shock. Behind this are balance sheet vulnerabilities, protracted weak demand and elevated uncertainty, which jointly triggered an adverse feedback loop of weak investment, weak productivity and bleak income prospects. Structural headwinds, already blowing before the crisis, include a waning ICT boom and slowing technology diffusion, partly reflecting an aging workforce, slowing global trade and weaker human capital accumulation.

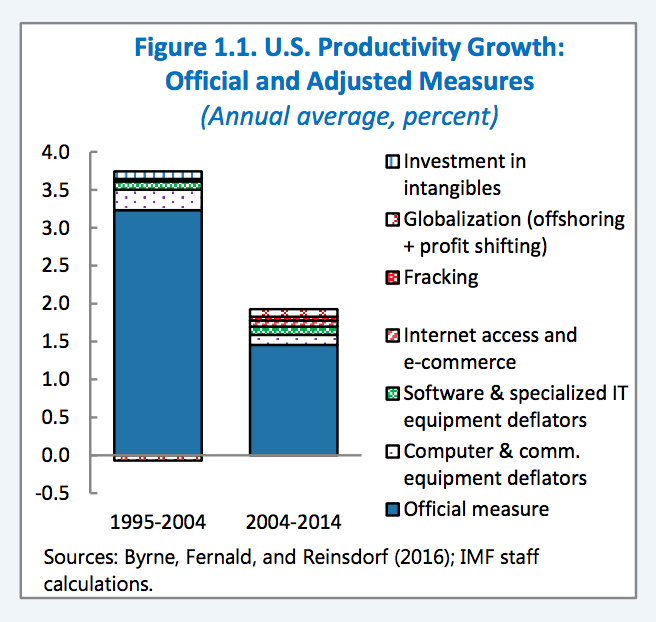

Because the pace of innovation in the hard-to-measure digital economy is very rapid, measurement error has been put forward as an explanation. Byrne et al. (2016) examine this issue in the US context and find little evidence that this slowdown arises from growing mismeasurement of the gains from innovation in information technology–related goods and services. First, the mismeasurement of information technology hardware is significant preceding the slowdown, so the quantitative effect on productivity was larger in the 1995–2004 period than since then, despite mismeasurement worsening for some types of information technology.

Second, many of the consumer benefits from the “new” economy are, conceptually, non-market: they raise consumer well-being but do not imply that market sector production functions are shifting out more rapidly than measured. Moreover, estimated gains in nonmarket production are too small to compensate for the loss in overall well-being from slower market sector productivity growth. In addition to information technology, other measurement issues that can be quantified (such as increasing globalisation and fracking) are also quantitatively small relative to the slowdown.

Chad Syverson conducts four disparate analyses, each of which offers empirical challenges to this “mismeasurement hypothesis”. First, the productivity slowdown has occurred in dozens of countries, and its size is unrelated to measures of the countries’ consumption or production intensities of information and communication technologies (i.e. the type of goods most often cited as sources of mismeasurement). Second, estimates from the existing research literature of the surplus created by internet-linked digital technologies fall far short of the $2.7 trillion or more of “missing output” resulting from the productivity growth slowdown.

Third, if measurement problems were to account for even a modest share of this missing output, the properly measured output and productivity growth rates of industries that produce and service ICTs would have to have been multiples of their measured growth in the data. Fourth, while measured gross domestic income has been on average higher than measured gross domestic product since 2004 — perhaps indicating workers are being paid to make products that are given away for free or at highly discounted prices — this trend actually began before the productivity slowdown and moreover reflects unusually high capital income rather than labour income (i.e., profits are unusually high).

A McKinsey Global Institute discussion paper undertakes a microanalysis and identifies six characteristics of the productivity-growth slowdown. These characteristics are low value-added growth during the recovery after the financial crisis; a shift in the composition of employment in the economy toward lower-productivity sectors; a lack of productivity-accelerating sectors after the financial crisis; weak capital-intensity growth; uneven rates of digitisation across sectors, where the least digitised often are the largest sectors, with relatively low productivity; and diverging firm-level productivity, with slowing business dynamism.

A closer look at the lack of productivity-accelerating sectors reveals that productivity performance of businesses and sectors does not slow down or speed up in unison. The shifts in aggregate productivity growth are rather the result of individual sectors accelerating and decelerating at different times. The productivity boom of 1995 to 2000 was characterised by an exceptional combination of large-employment sectors experiencing a productivity acceleration. In contrast, what is striking about the recent slowdown in productivity growth is the distinct lack of accelerating sectors, and the few that are accelerating are relatively small in terms of employment. This raises questions: is the lack of accelerating sectors temporary, or are there common patterns between industries that may be more permanent barriers to productivity growth?

Redmond et al (2017) examine the empirical relationship between credit conditions and total factor productivity growth during the financial crisis. They argue that tighter credit conditions may have contributed to the decline in total factor productivity: obtaining credit was more difficult and expensive for firms and the reduced credit supply may have prevented firms from investing in innovation and creating new jobs. The empirical analysis shows the crisis indeed altered this relationship. During normal times, total factor productivity growth fluctuates over the business cycle along with changes in the intensity with which available labour and capital are used; credit conditions are unimportant. During the crisis, however, distressed credit markets and tighter lending conditions were significant drags on total factor productivity growth.

Because productivity’s sensitivity to credit conditions once again diminished after the crisis, the post-crisis easing of credit conditions did not boost productivity growth. As a result, the financial crisis left productivity, and therefore output, on a lower trajectory. Adverse credit conditions appear to have dampened total factor productivity growth by curtailing productivity-boosting innovation during the crisis rather than by hampering the efficient allocation of the economy’s productive resources through reduced creation and destruction of firms and jobs.

Gavyn Davies argue that some of these headwinds caused by the GFC should have become less powerful as the economic recovery has progressed, especially in economies such as the US where labour markets have fully returned to normal. With US labour utilisation having little further room to grow, productivity has now, for the first time since 2008, become the main constraint on the GDP growth rate.

Fortunately, there seem to be a few early signs that productivity might be starting to recover in the US. In particular, the contribution to productivity growth derived from “capital services per hour worked” has started to rise, implying that investment may finally be improving, as it normally does late in the economic cycle. If confirmed, these signs support the theory that productivity will recover now that the headwinds from the GFC have started to abate and that it has important implications for our understanding of the “productivity puzzle”.

Noah Smith points out that productivity comes from the level of technology, the quality of government and the skills of the population – three things that are notoriously hard to boost and where many of the obvious steps have already been taken. Yet, Smith argues that a bit remains, and before countries go looking for ways to radically transform their economic and political systems, they should do the easy tasks that remain undone. The first is to raise government spending on research.

In many research domains increasing investments are needed in order to maintain the same rate of progress or open up entirely new fields. Second, there are some types of regulations that are detrimental to the economy, such as occupational licensing or restrictive land use regulation by tech hubs. Infrastructure repair is another obvious task, especially in the U.S. But the biggest piece of low-hanging fruit might be skilled immigration which, according to the best economic research available, raises the wages of native-born people in rich countries.

Tyler Cowen writes that one productivity problem is that we are only human. He suggests we should focus on how hard it is to build communities and how trying it can be to get people to see the world in the same way. That may sound entirely off point, but in many cases productivity improvements are difficult to accomplish because humans do not behave rationally. A significant percentage of humans can process material without much social reinforcement, but in most cases there seems to be a logic for the usefulness of face-to-face contact.

Cowen proposes three answers to the productivity problem. First, we can make online communities more vivid. Second, we can make face-to-face communities more effective. Third, individuals should read and cultivate Stoic philosophy in themselves: more self-reliance and less dependence on social cues for doing the right thing will increase economic performance. The enterprise of boosting the productivity of our robots and smart software is coming along just fine. We humans should take a look at ourselves for the next step.