There is growing debate about a common European military policy and defence spending. Such moves would have major economic implications. We look at the supply side and summarise some key facts about the European defence sector: its size, structure, and ability to meet a possibly increased demand from EU member states.

With a turnover of over €100 billion in 2015, the European defence industry does not rank among the largest manufacturing sectors in the EU. Nevertheless, the industry employs around 500 000 people directly and indirectly generates 1 200 000 jobs (in 2014). This gives the industry an additional importance beyond its inherent security aspect.

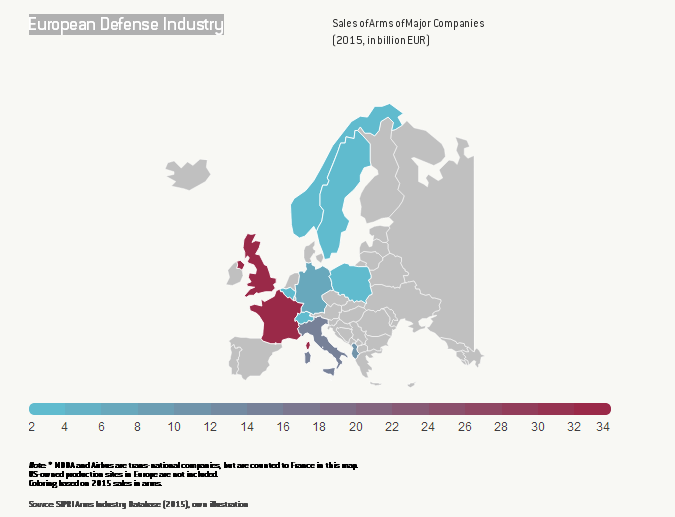

The structure of the European defence industry, similar to other manufacturing industries, is highly dispersed with a few large players and about 1350 small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). While companies are scattered over almost the whole EU, a few countries (Austria, Czech Republic, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom) host the bulk of SMEs as well as top companies.

SIDE NOTE: This “top group” consists of 31 companies covered by the SIPRI Arms Industry Database of the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI)

Even within the “top group” of European defence companies, yearly turnovers range between €0.5 billion and €23 billion EUR (average €3 billion). Employment ranges between 1900 and 154 000 employees (average 30 000 employees).

As shown in the map above, the UK, France, and Italy dominate the European market in terms of the number of active companies and their sales of arms. In the UK BAE Systems (LON:BAES) (€23 billion of arms sales and 82 500 employees) is the largest defence company. In France it is Thales (€7 billion and 62 000) and Safran (PA:SAF) (€4.5 billion and 70 000). In Italy Finmeccanica (€8 billion and 47 000) is the largest. In addition, Airbus, a trans-European company, ranks second (€13 billion and 136 000) in Europe after BAE Systems. Note that some of these companies are not exclusively producers of arms, which explains the varying ratios of sales to employees.

Looking at smaller companies is difficult because of a lack of information on Eurostat. However, the data which is available indicates that small companies are mainly active in the production of weapons and ammunition, while large companies focus more on vehicle production and aircrafts.

To sum up, the European defence sector is comprised of a few top players such as BAE Systems, Airbus, Finmeccanica, and Thales, along with hundreds of SMEs. A more harmonised and streamlined European defence policy might bring efficiency gains due to a further specialisation of countries, regions or companies in certain technologies.

The data presented here also show that the European defence industry is not evenly spread across the EU. This suggests that increased military spending by EU member states may not flow equally to all member states. For example, Germany may be one of the countries that will increase defence spending most strongly. But Germany’s domestic defence industry is comparatively small, and therefore might not be the destination of increased funding. If increased spending in one country flows to firms in other countries, this could result in new trade flows.