By David Messler

- Fuel prices have crept higher and higher this year, but the cause is quickly becoming a finger-pointing contest with no real winner

- Rising demand and dwindling supply are the true force behind the increase in gasoline and diesel prices

- While central banks can work to reduce demand, the market may struggle to solve supply issues

Oil prices are a common topic of conversation around the office water cooler these days. As you might expect, perspective matters. The folks at the Halliburton office in Midland, Texas likely view the advent of $100 WTI much more warmly than many others whose living doesn’t depend on it directly.

At the other end of the spectrum, truckers, the good folks who deliver everything from baby formula to hamburger patties, are pleading for relief from diesel prices that have doubled in the space of a year.

The old saying, “One man’s meat, is another man’s poison,” probably never rang truer. These pleas have caught the ears of many of our political leaders. With few exceptions, they have resolutely, and indignantly laid the blame for high gasoline, and diesel prices directly at the feet of the oil companies that produce, refine, and distribute these products.

The president also has made strident comments regarding oil companies. In a number of recent interviews, he has castigated them for diverting capital toward shareholders in lieu of break-neck drilling to raise oil supplies, with the desired outcome of lowering oil prices.

One can only wonder if the irony of that commentary is lost on the president.

President Biden has been frustrated in his attempts to reduce oil prices, or properly affix blame for them. Starting last year he publicly exhorted the Saudis to raise production to reduce prices.

The attendant irony of making this request to one of the top global oil producers seems to once again be lost on the Commander-in-Chief.

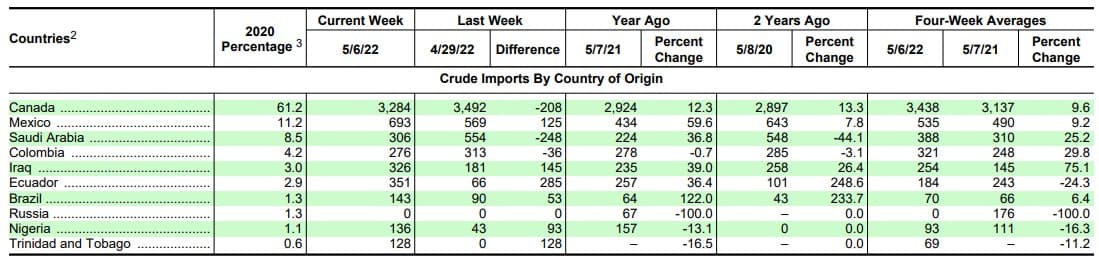

The Saudis, not so politely, demurred. In an odd pivot, he then sent emissaries to Venezuela to see if they might be of some help along these lines. Data contained in the most recent edition of the EIA-Weekly Petroleum Status Report-WPSR does not suggest this trip was fruitful.

Undeterred, earlier this year, plans were made to personally renew his insistence that Saudi Arabia begins to pump more. A notion that the Saudis quickly discouraged.

Shortly after receiving news of the visit being declined, President Biden then called the leader of Saudi Arabia, Sheikh Mohammed bin Salman—MBS, to make his case. Reportedly, the sheik was not available when the call was made.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine then supplied the president with an obvious bogeyman for the high cost of fuel. The president has often referred to “Putin’s war,” as being responsible for the high cost of driving for Americans. An assertion that doesn’t bear up under strict scrutiny.

There is a vague association that can be made, however, as the loss of Russian supplies, and near-universal embargoes, have stressed an already tight situation globally.

On two occasions, Biden authorized tapping the Strategic Petroleum Reserve—SPR, with the hope of dropping the cost of gas and diesel for consumers. He has also authorized refiners to keep the E-15 blend to increase supplies of fuel during the summer driving season.

Biden’s attempt to deflect blame for the high prices and the attempt to flood the market with oil have both been perceived as failures, and perhaps left people confused about the primary source of cost inflation in the world today.

In this article, we will examine some data points and make a determination as to whether oil companies are responsible for the high price of refined products.

Are high gasoline and diesel prices the direct result of high oil prices?

The high cost of the two primary transport fuels, gasoline and diesel, are on every pundit’s lips these days. You almost can’t turn on the TV without seeing a panel of talking heads opine about the historic high prices for this commodity, which moves the bulk of trade in global commerce.

High prices for diesel are certainly uncomfortably high and need to be brought into a normal framework ASAP. But are high oil prices the root cause?

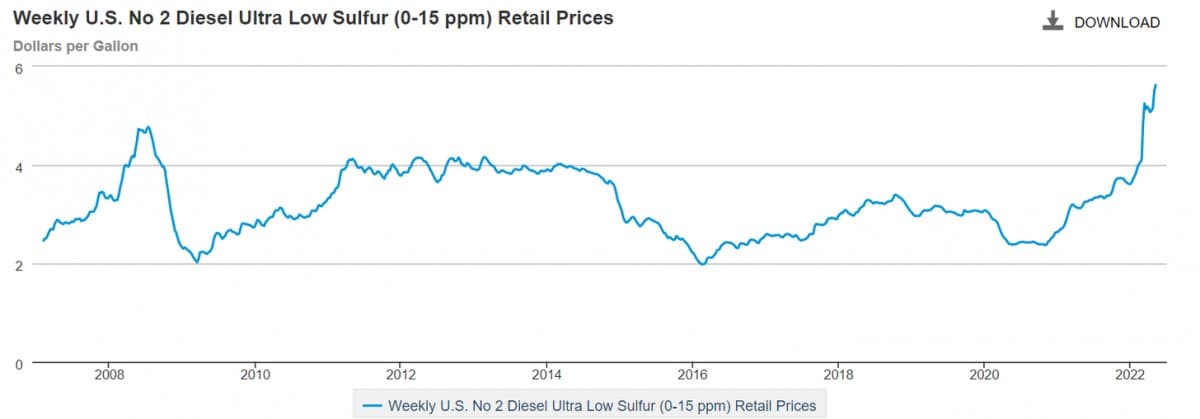

Have a look at the EIA graphic above. You can see I’ve put a 10-year range on it. If you go back to 2014, oil prices were above $100 a barrel. Now, look at the reference price for diesel.

It was right around $4.00 per gallon, a far cry from the $5.65 a gallon that is associated with the current, $100 oil price. What changed?

Root causes of high gasoline and diesel prices

First, let me acknowledge that there are a lot of moving parts here, and it’s tough to get too detailed without writing a 100-page essay. Avoiding that, we will take a quick look at the key contributors to prices that are 50% higher now, than the last time crude oil topped $100 per barrel.

Reduced refining capacity is our first stop. In 2020 refining capacity declined by about 900K BOPD due to a number of plant closures. Demand was muted for the first half of 2020, but surged back as the promise of a vaccine gave people confidence that stepping outside their door was not a death sentence.

By the time May of 2022 rolled around, we had almost matched 2019 passenger volumes.

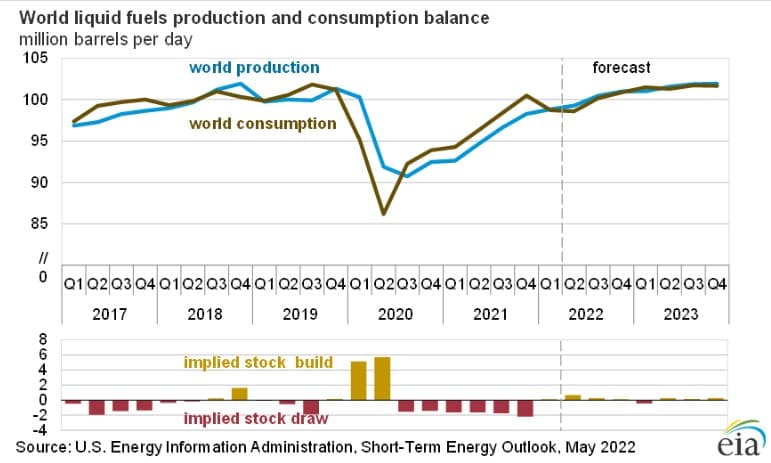

In the EIA graphic below you can see the supply and demand curves charted for the past few years. In 2022, the lines begin to overlap, and it should be noted, this does not include the effects of the projected loss of 40-50% of the former 10 mm BOEPD, produced by Russia.

In other words, there is probably a gap between demand and supply of about 4-5 mm BOEPD.

As Bloomberg notes, we are exporting more. Thanks to European refinery closures they need some of our supply, with several hundred thousand barrels being shut down, or in some cases being converted to biofuels. The linked Bloomberg article shows we exported a million barrels a day earlier this year.

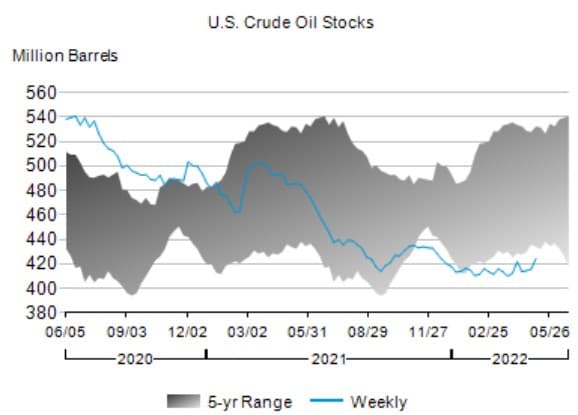

Inventories in the U.S. are down substantially below 5-year averages and have held in a 410-420 mm barrel range since Q-4 of last year. That may sound like a lot, but at consumption rates of about 20 mm BOPD, it’s about a 17-day supply.

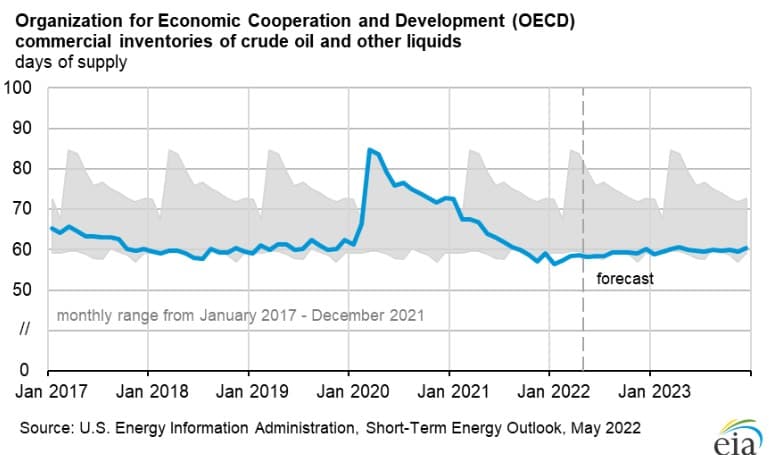

OECD inventories are in the same fix with the current ~60-day supply, well below the normal ~80 mm bbl supply for this time of year.

In each case, surging demand is meeting low inventories, and contributing to prices pushing inexorably higher.

All of that brings us to the big reason for high refined product prices that diverge from the last time oil topped $100 per barrel. The money supply has been increasing gradually since the financial meltdown of 2008.

With what is termed an “Accommodative” monetary strategy, the Fed has kept interest rates artificially low since that time creating asset bubbles of various classes, but particularly in stocks.

Savers have had no option but to invest in stocks for yield. And, the Dow index has risen from 7K in Feb of 2009, to nearly 37K in recent months.

You can see the curves for the stock market and the money supply track each other closely. Aided by the Fed’s printing press, people poured money into the stock market, pushing it ever higher.

Inflation was kept in check for most of this period by an ample supply of goods and services.

The COVID-19 shutdown that began in March of 2020 introduced a new wrinkle in global commerce. Supply chains and logistics were affected for the first time causing bottlenecks and backups that created substantial gaps between surging demand, and the supply of everything.

This occurred just as the U.S. Fed and Central Banks around the world began injecting liquidity into the system. Inflation had to be the result, and the rise from 0.5% in 2020 to the present day is charted below.

So what’s next for oil and gas and refined products?

The U.S. Central Bank, the Federal Reserve has begun to shift its 15-year-old posture of “Accommodation,” to remove excess liquidity from the system by increasing the discount rate—the rate it charges lending institutions and reducing asset-bond, purchases.

The posture is known as “Tightening.” This will have the effect of increasing the interest rates paid by consumers and corporations and dampening demand for everything, including petroleum refined products.

Reduced demand will begin to relieve upward pressure on the prices of gasoline and diesel. To what degree remains to be seen. We still have all the other problems that make it an open question as to when or if they will begin to decline toward more affordable levels.

Mixed messages from the government and outright obstruction in the form of over-regulation, and reduced leasing opportunities cast a shadow on the future supplies of crude oil.

Your takeaway

Hopefully, now you have a more complete picture of why gasoline and diesel prices are so high. Oil companies are not to blame for high prices or inflation. They are price takers in a global market, not price makers.

Prices are set by a combination of market forces, and government intervention. Right now the price of diesel and everything else largely reflects those forces and dilution (debasement) of the currency that occurred over the last several years.

Only time and action by the Central Banks can begin to relieve the monetary inflationary pressures we have discussed. The other factors, reduced refining capacity, low inventories, supply chain woes, and lack of upstream investment will take their own toll, providing support for current prices and possible lift in spite of everything governments do to bring them down.

Related: Highest Ever U.S. Gasoline Prices Aren’t Destroying Demand

Which stock should you buy in your very next trade?

AI computing powers are changing the stock market. Investing.com's ProPicks AI includes 6 winning stock portfolios chosen by our advanced AI. In 2024 alone, ProPicks AI identified 2 stocks that surged over 150%, 4 additional stocks that leaped over 30%, and 3 more that climbed over 25%. Which stock will be the next to soar?

Unlock ProPicks AI