Who is Kevin Hassett? Wolfe looks at the Trump ally tipped to become Fed Chair.

The economic policy debate is still dominated by Keynesian central bankers and politicians, even though the financial authorities have demonstrated a clear lack of discipline in implementing Keynes’ model of surplus in good times to finance deficits in bad times.

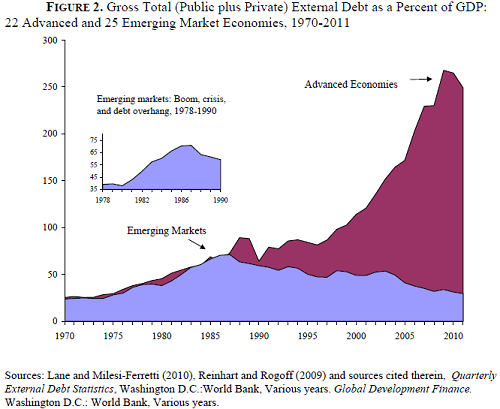

The current modus operandi in the West has become worryingly dependent on the ability of the central planners to pull their favoured economic levers whenever ‘necessary’. If you don’t believe this, take a look at the graph below:

Research from Reinhart et al in Q2 of this year has once again proved a welcome addition to the debate. Carmen and Vincent Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff are seen as international experts on the economic implications of debt, and their new research paper, ‘Debt Overhangs: Past and Present’, is well worth a read.

For anyone following our inspirations in what goes into these pages, this recent research continues the themes addressed in Reinhart and Rogoff’s excellent 2009 book, ‘This Time Is Different’.

Implications Of Too Much Debt

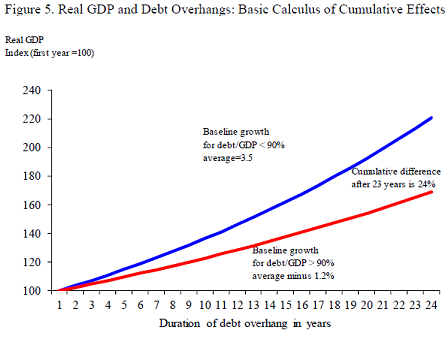

Debt Overhangs looks at economic performance in developed nations since 1800, when debt/GDP ratios exceed 90% for at least five years, and the authors make some important findings. The paper notes that public debt overhangs are associated with weak economic growth of 1.2% less than growth found in lower debt periods. Typical economic growth in GDP of 3.5% per annum is reduced to 2.3% per annum. The authors also note that our record debt levels might even have potentially greater negative effects on growth. This seems plausible, as larger debts mean greater interest payment burdens, further diverting productive capital from a useful home.

We have often argued in these pages that excessive debt chokes our economic motor, as too much potentially productive capital is lost to servicing interest payments.

Long-Term Effects

Beyond this we should particularly note the authors’ new findings on the long term negative effects on economic growth. This reduced economic growth seems to have such a significant impact due to the long term duration it exhibits itself over.

Within the sample period, 26 episodes of debt overhang were found, of which 20 last more than a decade. And, of the 26 episodes the average duration is found to be ~23 years. As the authors comment: “the long duration also implies that cumulative shortfall in output from debt overhang is potentially massive”. Losing growth of 1.2% a year really compounds over time, as the authors’ graph below shows:

But is debt an issue with low interest rates?

In a word: yes.

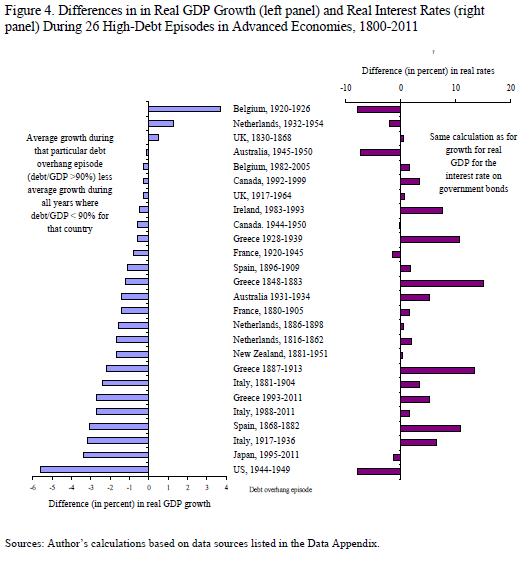

Reinhart et al find that the negative effects of debt on economic growth exert themselves even when the debtor nations are able to keep borrowing at low interest rates.

“We find that growth effects are significant even in the many episodes where debtor countries were able to secure continual access to capital markets at relatively low real interest rates. That is, growth reducing effects of high public debt are apparently not transmitted exclusively through high real interest rates”.

The chart below shows the authors’ findings here across these 26 debt overhangs:

Is This Research A Lone Star?

Given the conclusions of this latest research from Reinhart and Rogoff, you might think this is interesting but question how common such academic findings are.

Well, these findings are common enough for there to now be a significant body of highly regarded, peer-reviewed research arguing in this direction.

The authors’ latest research adds to their own extensive library of books, journal publications and research papers, alongside research with similar conclusions such as:

- ‘The Real Effects of Debt’ by Cecchetti, Mohanty, and Zampolli, August 2011

- ‘Government Size and Growth’ by Bergh and Henrekson, April 2011

- ‘The Impact of High and Growing Government Debt on Economic Growth’ by Checherita and Rother, August 2010

- ‘Public Debt and Growth’ by Kumar, Mohan, and Jaejoon Woo, July 2010

Politicians use the word ‘growth’ more than almost any other term when discussing the economy and continuing financial crisis. Just note how often the word appears in the speeches of Obama, Cameron and various Eurocrats.

Leaning on the justification of growth is fine, but to help achieve some actual growth means surrounding yourself with the best advisers, carefully listening to what the breadth of economic research suggests, and then designing the appropriate policy responses.

At the moment the Obamas, Eurocrats and even Camerons (not much debt reduction happening in the UK!) of the world often surround themselves with old names with wrong-headed ides. Obama’s inner circle is especially revealing here, with the inclusion of Lawrence Summers being an example of the problem at hand. These economic inner circles also tend to bare most attention to the academic research of the likes Bernanke, Krugman and Eichengreen, and act in the belief that we need to keep spending and borrowing to create growth and later surplus.

Debt And Solvency

The implications of debt are not well respected by these economic elites. Today’s problems are of debt and solvency, not a lack of liquidity. We are not able to solve things by just adding a bit more debt now, and then pay it off a few years down the line. Reinhart et al make a finding that debunks the Keynesian assumption that we can increase spending and debt levels in line with the business cycle, noting that “the long duration (of debt overhangs) belies the view that the correlation is caused mainly by debt build-ups during business cycle recessions”.

The findings of Reinhart et al need more attention, if we are to avoid more short-termist fiscal and monetary policy. The longer we ignore debt, and provide liquidity and loose monetary conditions, the greater continued negative effect this debt will have.

When looking at current economic policy actions, Sprott Asset Management joke in the title of their latest commentary that ‘The Solution… is the problem’. We couldn’t agree more.