Nobody has made the case for unpredictability of complex systems or examined the risks of using past events to predict future ones better than author Nassim Taleb.

But perhaps no one has felt this dilemma more acutely than your Thanksgiving turkey.

In his book, Anti-Fragile, Taleb describes what he calls The Great Turkey Problem:

A turkey is fed for a thousand days by a butcher; every day confirms to its staff of analysts that butchers love turkeys ‘with increased statistical confidence’. The butcher will keep feeding the turkey until a few days before Thanksgiving. Then comes that day when it is really not a very good idea to be a turkey. So with the butcher surprising it, the turkey will have a revision of belief – right when its confidence that the butcher loves turkeys is maximal and ‘it is very quiet’ and soothingly predictable in the life of the turkey.

It’s an astute allegory on the seemingly universal human belief that we can predict the future despite much evidence to the contrary.

Our ingrained tendency is to assume that, because things have a gone a certain way for so long, they will continue to do so. This is the mindset that can be attributed to nearly every crisis and major event, such as:

- The mining and metals crash of 2012;

- The housing market crash/global financial crisis of 2008; and

- The ‘Long Peace’ leading up to WWI.

The data is often clearly advertising the risk of extreme events, and, despite the arm waving of a few Cassandras (think Michael Burry in the Big Short), our brains have a hard time extrapolating a situation beyond the immediate past.

Or, put more simply:

Because of this tendency I try to remind myself to suspend belief in the ability of “experts” to predict metal prices (or the future of anything). A quick review of the track record of nearly any mining analyst tends to make this easy, as their long-term success rates tend to be about on par with a coin toss.

But to give the poor analysts a break, this makes sense as they’ve essentially been set up for failure.

The number of factors at play are usually staggering in their complexity, and the ability to capture, organize, interpret and then shoehorn that information into anything resembling accuracy is a monumental feat.

However, what we can do (on Taleb’s advice) is bet against complexity and those trying to predict the outcome of complex systems.

Not Only Electric Vehicles

This all came to mind as I was reading about the platinum market. The general narrative is this: electric vehicles will soon take over, Europe (and everybody else) is cracking down on diesel, and the need for the catalytic converter is all but dead.

As approximately 40% of platinum mined goes to use in the catalytic converter, the logic follows that the demand will be crushed and, therefore, the price will follow suit.

A case is occasionally made that growth in China and the developing world will keep up demand for the diesel engine in the medium term, but, even so, in the fullness of time the EV will conquer and platinum is doomed.

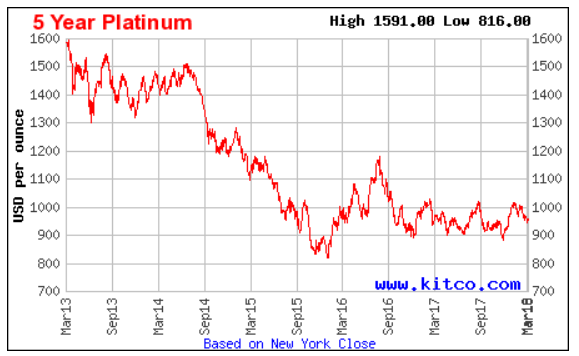

This may very well all be true, and is certainly reflected in the near past.

But remember: The world is complex, not linear.

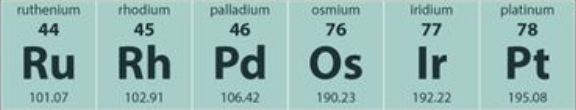

Platinum is only the most famous member of a group of metals aptly named the platinum group metals or PGMs. These elements are grouped together, both on the periodic table and in life, due to their similar properties and tendency to be found together in the same deposit:

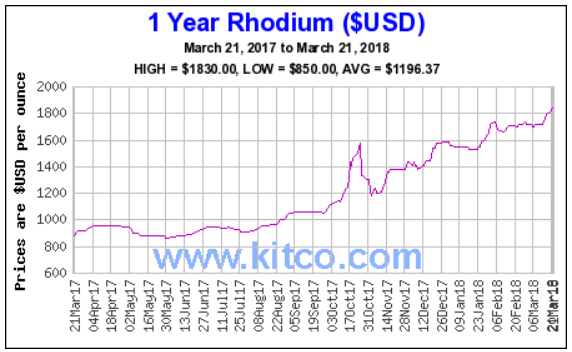

And while platinum has suffered a beating over the past five years, its cousin’s palladium (Pd) and rhodium (Rh) have been on a serious roll.

Palladium was the best performing metal of 2017, reaching an all-time high of $1,139 per oz. last January. Rhodium has more than doubled in the past year skyrocketing from $800 per oz. to over $1,800 per oz. The price of these metals are driven primarily by their use in automobiles for pollution reduction.

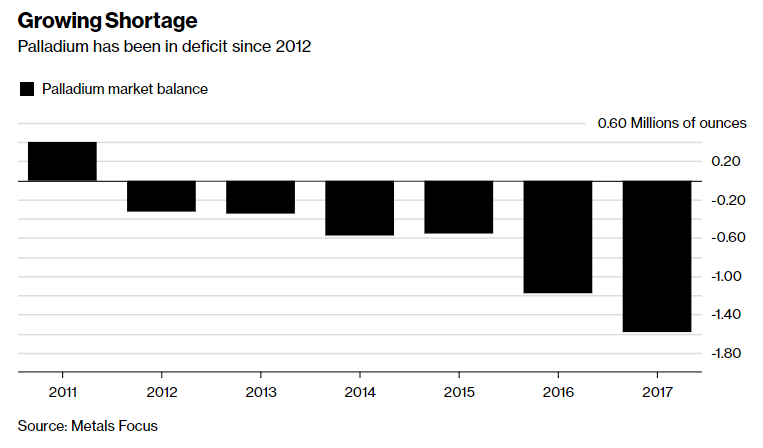

However, unlike platinum that is used to reduce diesel emissions, Pd and Rh are used in gasoline powered vehicles, and it appears that the specter of EVs has done nothing to dampen appetites. Demand has far out-stripped production since 2012, which has resulted in a subsequent price squeeze and pressure on stockpiles.

What Does This Mean for Platinum?

The similarities between the platinum group metals means that, for certain purposes, they are interchangeable. If the prices of Pd and Rh continue to rise it’s conceivable that automakers may make the switch to the use of platinum in gas powered engines.

This is not going to happened overnight, the retooling of auto plants to utilize platinum would not come cheaply and will likely require a further depletion of PGM stockpiles. But, while palladium may have hit a new ceiling rhodium is nowhere near its early 2000’s price of $10,000 per oz. (not a typo!).

The average South African PGM producer extracts an ore comprised of roughly 60% platinum, 30% palladium and 10% rhodium, which means proportionally there should always be a greater supply of platinum making it the more reliable metal. Thus, it’s not inconceivable that automakers will make the jump to using the more plentiful platinum.

But the real elephant in the room affecting all PGMs is South Africa.

The Ramaphosa Problem

South Africa produces approximately 90% of the worlds platinum and much of its palladium (second only to Russia). It currently holds 80% of the worlds known PGM reserves.

When Cyril Ramaphosa was elected President last year the mining and business community were excited to welcome the “pro-business” politician. To say that they’ve been disappointed is a serious understatement.

Despite initial hopes for the country’s new leader, he began his tenure by ripping up the most recent mining charter (completed in 2017) with plans to roll out a revised version this May. The new charter will require 30% black ownership of mines as well as requiring miners to guarantee that at least 80% of their total spending goes to local firms, including a minimum of 65% of spending going to black-owned suppliers.

To make matters worse, SA appears well on its way to widespread land nationalization a topic Chris covered recently here. Last month the ruling African National Congress (ANC), together with opposition party the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), voted to change the country’s constitution to reduce property rights.

EFF leader Julius Malema told reporters after the vote that the push is for all the land, including farms and urban properties. “Every land in South Africa should be expropriated without compensation,” he said. “The state should be the custodian of the land.”

Not good.

Well, not good for South Africa at least, but potentially very good for PGMs. In fact, there may be no better way to be short South Africa than to be long platinum.

With dropping production rates, stringent ownership requirements, and the looming threat of nationalization affecting 90% of the world’s PGM supply, platinum prices could see a major upswing in the coming year.

Avoiding the Turkey Problem

The problem with turkeys is that they tend to assume complex issues have simple answers. Which is why, given time, both the literal and the figurative tend to find themselves in an undesirable situation.

PGMs, like most metal pricing, is complex and cannot be reduced to any single issue or even the few discussed here. I tend to agree that in the fullness of time electric vehicles will come to dominate the market; but this will not happen overnight, or even in the next 5 years. Gasoline powered, and even diesel, vehicles will continue to be an integral part of society in the coming years, especially in developing countries.

I’ve considered the idea that the developing world may simply “skip” the personal hydrocarbon vehicle and go straight to some form of electric ride sharing, much as they skipped the telephone landline and went straight to cell phones. I think this is true to a degree and will be the likely fate of the working class. But the infrastructure isn’t there yet for mass adoption of EVs, nor is it coming on fast enough.

As economic tides continue to rise around the world and drag people into the middle consumer class there will continue to be a demand for personal vehicles; for the medium term at least, the majority of those will be hydrocarbons (and PGMs).

Coupled with instability in the world’s major platinum producing regions and intense pressure on PGM stockpiles, I’d be willing to bet that platinum starts to move in the same direction as its more en vogue cousins.

Complex systems act in unpredictable ways. It’s impossible to predict the future, but often the best way to do so is to bet against those that think they can.

The most difficult part about PGMs is finding exposure to good assets and good teams outside of South Africa. In the coming weeks we’ll be exploring opportunities in the space and looking at leaders best positioned to leverage the current climate.

In the meantime, perhaps consider a ham this Easter?