Mexico will have a new President on December 1. Falling short in each of the prior two elections, Andrés Manuel López Obrador won convincingly this time. Though a thorough leftist, AMLO, as he is called in Mexico, ran on the familiar populist, anti-establishment topics. For yet another country its political background has shifted dramatically.

Mexicans are apparently completely fed up with violent crime and the thorough corruption that accompanies it. Both of those priorities, however, have been priorities for a long time south of the US border. What’s different in 2018 is the absence of economy. It’s quite natural for any population to perhaps put up with a lot of negatives if things are going well. When they aren’t, everything is up for revision.

This has been the most violent election campaign in Mexico in living memory. Now that voting day has arrived, however, many Mexicans see it as an opportunity to remove the government that has led the country to this point.

Millions of ordinary Mexicans are angry at President Enrique Peña Nieto and his administration, particularly over the sluggish economy and widespread corruption, crime and impunity.

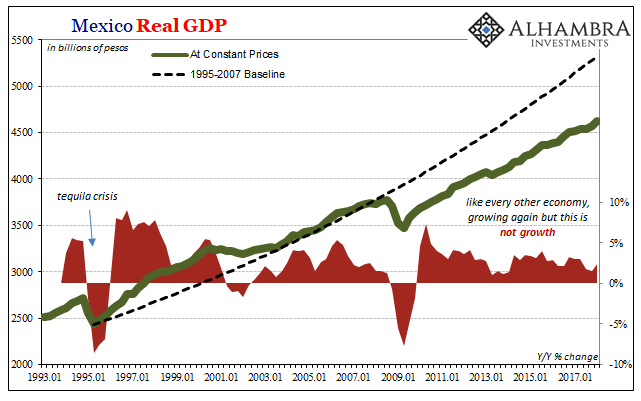

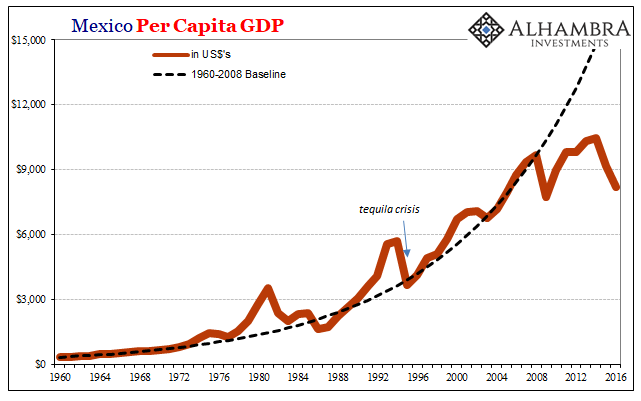

“Sluggish” is putting it mildly, though if this were the US economy it would be described as “prosperous.” Like so many other places around the world, Mexico’s system is growing but it hasn’t actually experienced growth in over a decade. That’s something deeper and more troublesome than mere sluggishness; thus, political paradigm shift.

Prior to AMLO’s victory, there were rumors he would add Guillermo Ortiz to his prospective cabinet. A globally respected former central banker, Ortiz would add significant weight to the populist attempt at finding a solution. He has prior experience, though not quite like this.

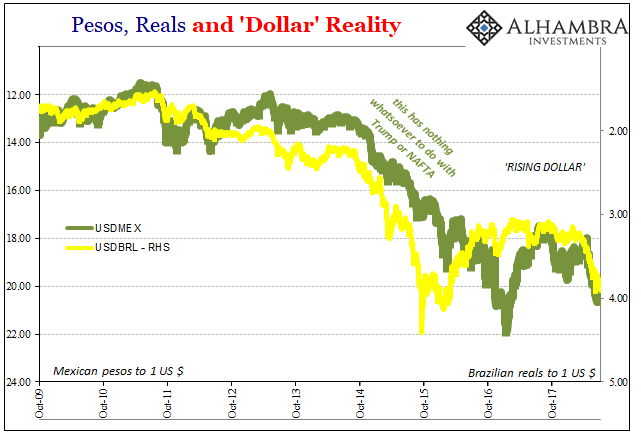

Ortiz was also Mexico’s Finance Minister in 1994 and 1995 during the so-called Tequila Crisis. It was a currency/peso disaster not anything related to the alcoholic beverage. The details aren’t important here in this context, suffice to write that it was in every way a precursor (“dollar”) of the Asian flu, which followed several years later.

Mexico suffered actual devaluation as well as the humiliation of a bailout arranged at the behest of the United States.

Notice, however, the difference. Though the Tequila Crisis was and remains the worst economic setback for Mexico since the 1930s, there was no lasting damage from it. Mexico’s economy recovered quickly and then grew rapidly for the rest of the nineties. It is from this result which puts Guillermo Ortiz back in the spotlight.

He would be wise to perhaps politely decline any invitation by AMLO. What’s happened over the last decade in Mexico is all-too-familiar, except if you are an Economist trained at the usual pedigreed academic institutions. Ortiz studied at Stanford, which merely means he won’t have the slightest idea why Mexico’s economy has deviated so sharply since 2008; even though a huge clue is given to everyone by the date of departure.

In other words, neither Mexico’s new government nor Banxico has any real influence over the economic or monetary trajectory. It’s all guided by the peso, which means “dollar.” In dollar terms, you can see why the populist AMLO won so big this time compared to those previous two electoral defeats:

Before 2008, Mexico had experienced currency problems but those had followed debt-fueled periods of extremely robust growth. They were, to put it simply, reversions to the mean; the Tequila Crisis being a really devastating one.

The last decade, by contrast, isn’t that. The economy no longer grows at all, not real growth anyway just the usual positive numbers. But it still suffers the peso all the same. Mexico’s currency began slumping long before anyone took Donald Trump’s campaign seriously. It’s not NAFTA that is causing the deficiency, but it is the uncertainty over NAFTA’s future that weighed so heavily on this election.

When things haven’t been going right for a very long time, a campaign issue like the possible alteration of trade benefits can end up being the final straw. Mexicans, like Italians or Brazilians, simply don’t want to fall any further behind. Given how the economy is always framed by every country’s establishment in the same most charitable terms, eventually the population won’t accept the same old rhetoric. Enough is enough; the breaking point is different each time, but the result politically is increasingly the same.

The world’s pre-2007 status quo is breaking down because the global economy did. There is increasing fragmentation all over. The worldwide system has never recovered, though in some places it has been better and a bit more stable than in others. James Carville’s vulgar summation applies here more than it did during that contentious 1992 US Presidential election which brought up “free trade” and gave us Ross Perot’s warning for the eventual “giant sucking sound.”

The economy, stupid. Only the cause of the economy’s break is the euro-dollar system. It’s the “dollar,” stupid.

It seemed great on the way up, even making central bankers look good who really had little idea during its ascent. After ten plus years on the way down, though, the only constant is that there are no winners. Not even AMLO. The Mexican people will have given him the unenviable task of trying to figure out what to do about a global system orthodox Economists still don’t understand nor admit.

Devaluation isn’t an option (see MXN above), nor is a bailout (ask Argentina how that’s going). Mexico’s problem is everyone’s problem, starting with economists.