America’s largest pension fund, the California Public Employees Retirement System (CALPERS), reported a 1% return on its investments for the 12 months that ended June 30, 2012. This disappointing return fell woefully short of the plan’s target return of 7.5%.

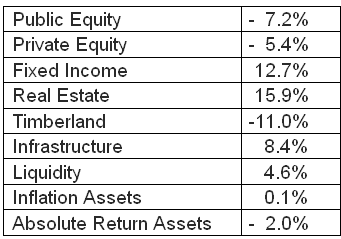

An analysis of the plan’s returns by asset class showed the following:

While a single years’ performance should not be treated as dispositive, CALPERS’ experience is dispositive of a number of anomalies that arise in a zero interest rate environment.

CALPERS’ performance is a case study in the challenges facing large pension fund (and all investors) in a world without yield. The fact that fixed income produced a double digit return while equities produced large losses unveils some of the fallacies that continue to govern institutional investment thinking. Conventional thinking has argued that equities are far more attractive than fixed income in an environment where bonds pay very low interest rates and stocks are trading at reasonable price/earnings multiples. Yet as CALPERS and other investors have discovered to their surprise, fixed income is producing stellar returns while public and private equity are not.

CALPERS attributed its stock market losses in part to poor manager selection, but many equity managers (including equity-oriented hedge funds) disappointed in 2011 and continue to do so in 2012. Such widespread underperformance speaks to the asset class rather than the practitioners. In contrast, 10-year Treasuries have offered increasingly low yields for the privilege of loaning money to the spendthrift U.S. government. Nonetheless, the return on these instruments (which some have described as certificates of confiscation) have been extremely high over the past two years.

CALPERS’ returns do not tell us much about the risk-adjusted nature of the returns. Disappointing private equity returns are a case in point. Despite the fact that private equity lost less money than public equity, the private equity performance was arguably much worse once it was adjusted for the characteristics of private equity funds: egregiously high fees; high leverage; concentration risk; and illiquidity. And let us now forget how this asset class imploded in 2008 and is still digging out from that disaster.

Institutions remain convinced that they must have large allocations to private equity. This is a result of the success of early investors in private equity such as the Yale University Endowment Fund led by David Swenson. But early investors participated in early private equity firms’ monopoly profits. The industry has since become overcrowded and risk-adjusted returns are now poor. Many institutions are increasing their allocations to private equity; it is time to rethink that approach.

The men and women managing large pension funds have a difficult task. But they need to revise their thinking about asset allocation. They rely too much on consultants, who in turn rely too much on conventional thinking that has proven time and again to be misguided. Traditional notions of asset allocation continue to lead institutions into traps such as excessive allocations to private equity that lead to unacceptably low returns. It is time for a new intellectual regime that recognizes that low interest rates are here to stay but neither assures low fixed income returns nor promise high equity returns.

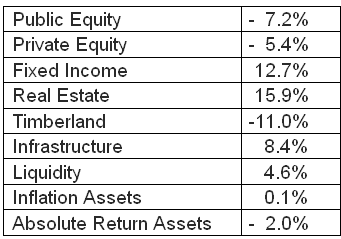

An analysis of the plan’s returns by asset class showed the following:

While a single years’ performance should not be treated as dispositive, CALPERS’ experience is dispositive of a number of anomalies that arise in a zero interest rate environment.

CALPERS’ performance is a case study in the challenges facing large pension fund (and all investors) in a world without yield. The fact that fixed income produced a double digit return while equities produced large losses unveils some of the fallacies that continue to govern institutional investment thinking. Conventional thinking has argued that equities are far more attractive than fixed income in an environment where bonds pay very low interest rates and stocks are trading at reasonable price/earnings multiples. Yet as CALPERS and other investors have discovered to their surprise, fixed income is producing stellar returns while public and private equity are not.

CALPERS attributed its stock market losses in part to poor manager selection, but many equity managers (including equity-oriented hedge funds) disappointed in 2011 and continue to do so in 2012. Such widespread underperformance speaks to the asset class rather than the practitioners. In contrast, 10-year Treasuries have offered increasingly low yields for the privilege of loaning money to the spendthrift U.S. government. Nonetheless, the return on these instruments (which some have described as certificates of confiscation) have been extremely high over the past two years.

CALPERS’ returns do not tell us much about the risk-adjusted nature of the returns. Disappointing private equity returns are a case in point. Despite the fact that private equity lost less money than public equity, the private equity performance was arguably much worse once it was adjusted for the characteristics of private equity funds: egregiously high fees; high leverage; concentration risk; and illiquidity. And let us now forget how this asset class imploded in 2008 and is still digging out from that disaster.

Institutions remain convinced that they must have large allocations to private equity. This is a result of the success of early investors in private equity such as the Yale University Endowment Fund led by David Swenson. But early investors participated in early private equity firms’ monopoly profits. The industry has since become overcrowded and risk-adjusted returns are now poor. Many institutions are increasing their allocations to private equity; it is time to rethink that approach.

The men and women managing large pension funds have a difficult task. But they need to revise their thinking about asset allocation. They rely too much on consultants, who in turn rely too much on conventional thinking that has proven time and again to be misguided. Traditional notions of asset allocation continue to lead institutions into traps such as excessive allocations to private equity that lead to unacceptably low returns. It is time for a new intellectual regime that recognizes that low interest rates are here to stay but neither assures low fixed income returns nor promise high equity returns.