The lag effect of monetary policy changes will surprise the Fed as the fiscal “pig” of stimulus begins to exit the economic “python.”

For those unfamiliar with the term “pig in a python,” it refers to when a python consumes its prey. It does so by swallowing it whole, in this case, a pig. The American-English definition of “pig in a python” became an analogy for the demographic bulge in the U.S.

– the people who were born during the ‘baby boom’ of the years immediately following the Second World War (1939-45), considered as a demographic bulge;

– any short-term increase or notably large group.

We can apply that analogy to the massive fiscal and monetary stimulus injected into the “economic python” in 2020-21. As discussed previously, those massive monetary and fiscal inputs were the root cause of the current inflationary spike. To wit:

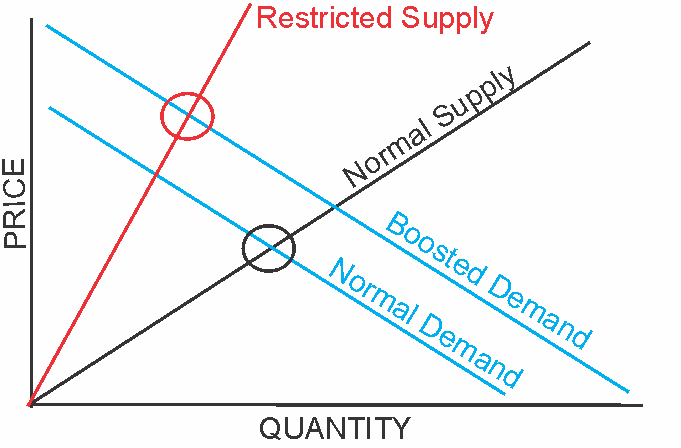

“As Milton Friedman once stated, corporations don’t cause inflation; governments create inflation by printing money. There was no better example of this than the massive Government interventions in 2020 and 2021 that sent subsequent rounds of checks to households (creating demand) when an economic shutdown constrained supply due to the pandemic.

The following economic illustration shows such taught in every “Econ 101” class. Unsurprisingly, inflation is the consequence if supply is restricted and demand increases by providing “stimulus” checks.”

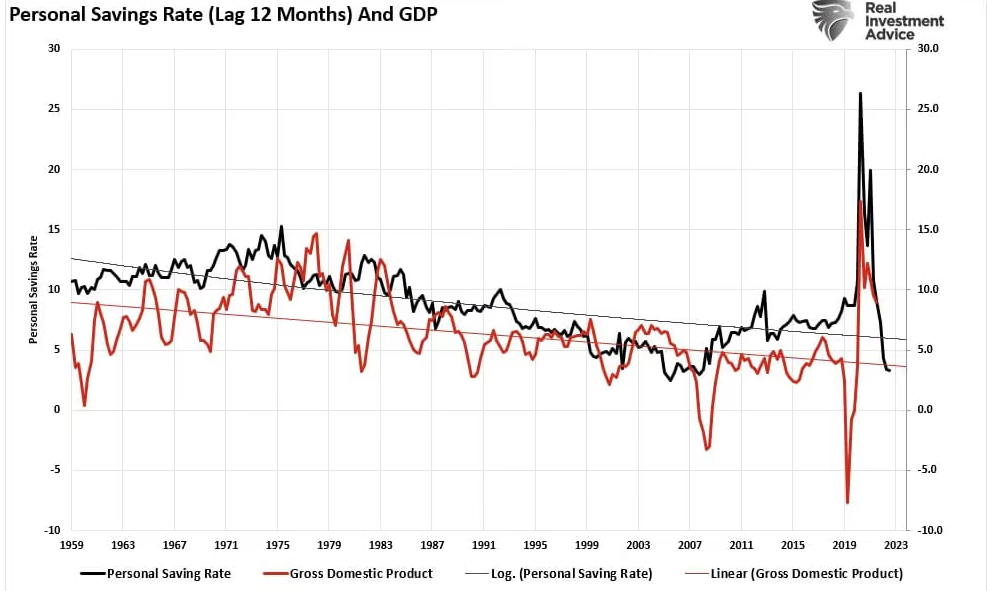

The massive surge in stimulus sent directly to households resulted in an unprecedented spike in “savings,” creating artificial demand. As shown, the “pig in the python” effect is evident. Over the next two years, that “bulge” of excess liquidity will revert to the previous growth trend. Economic growth will lag the reversion in savings by about 12 months. This “lag effect” is critical to monetary policy outcomes.

Since 1980, personal savings and economic growth have continued to decline. That correlation is obvious, considering economic growth is ~70% consumption. Unfortunately, due to the massive debt loads, the natural economic growth rate is below 2%. Such is evident that following each “crisis event,” the trend of economic growth continues to slow.

As noted, the “lag effect” of monetary policy will become more problematic for the Federal Reserve in the months ahead.

The Bulge And The Lag

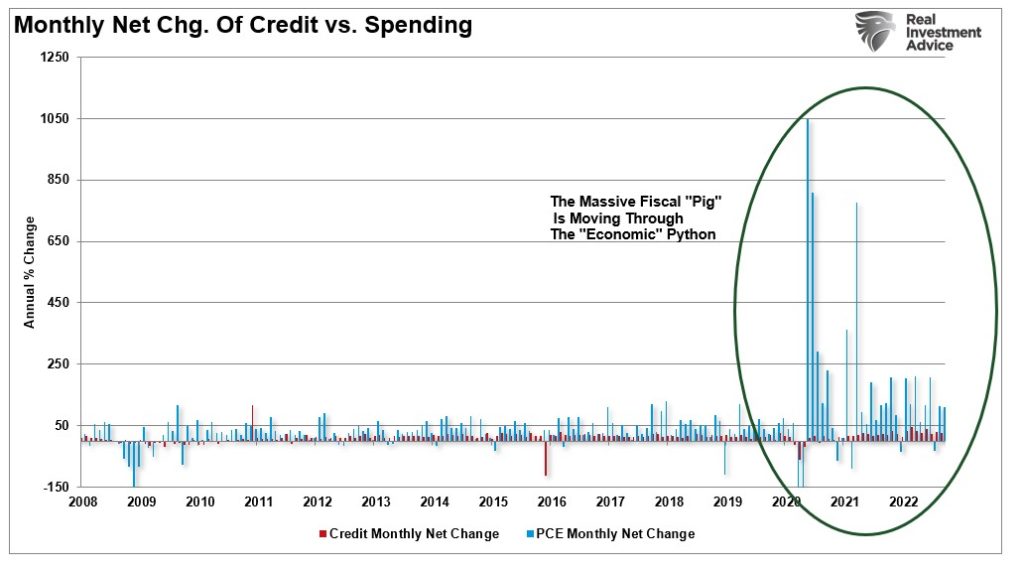

As noted, personal consumption expenditures (PCE) comprise roughly 70% of economic activity. The chart below shows the monthly net change in PCE and credit card debt. The surge in spending following the $5 trillion in the fiscal stimulus is apparent. Currently, that spending is running well above the long-term average even though it continues to revert.

That bulge in spending is pulling forward future consumption. In other words, as households received stimulus money, they spent it on things they would have bought in the future. For example, many individuals bought new computers to work from home, made household improvements, or purchased a new car. The problem with “pulling forward” future consumption is that it creates a void in the future. If that void remains unfilled, it will drag on economic growth.

The remnants of the fiscal “pig” in the economic “python” is masking the effects of higher interest rates and more restrictive monetary accommodation. While the tighter monetary policy will eventually bite deeply into economic growth, there is an extended “lag effect” as excess liquidity provides a buffer. However, as shown, while increases in credit and the remnants of fiscal largesse continue to support spending, the reversion to historical norms is inevitable.

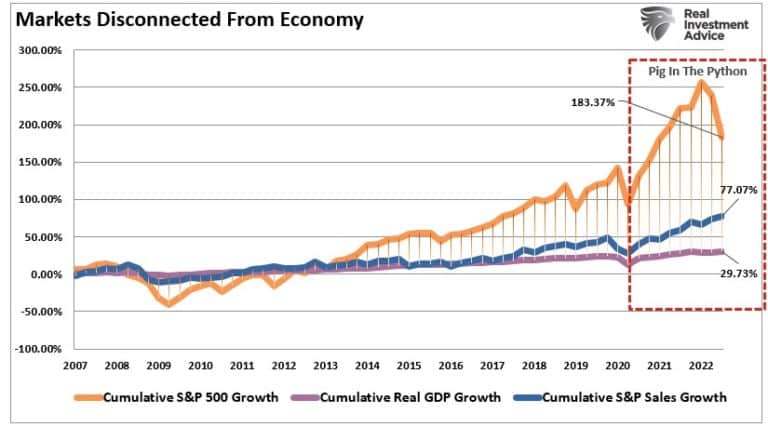

As the “pig” exits the “python,” the lag effect will catch up to stock prices that have vastly outgrown corporate revenue and economic growth.

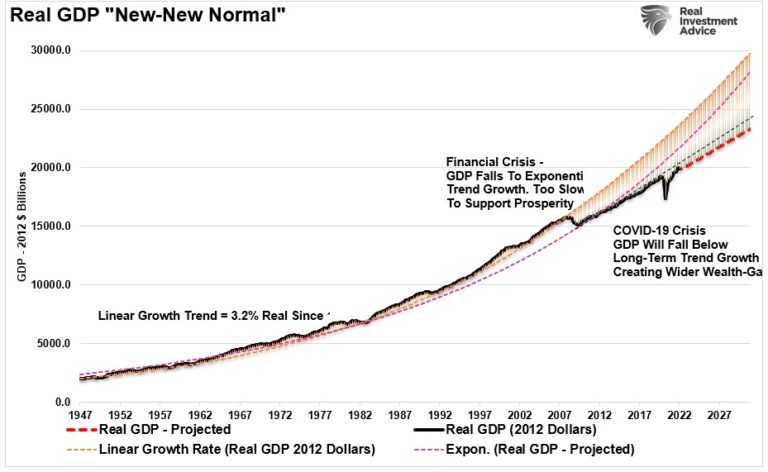

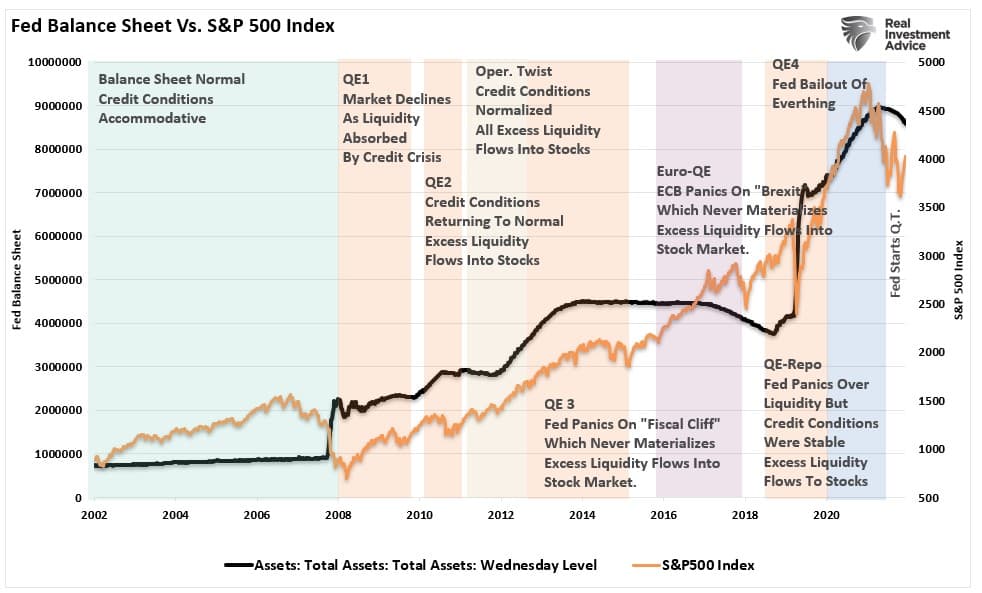

Of course, that massive divergence in asset prices from underlying fundamental growth is attributable to repeated rounds of monetary interventions by the Federal Reserve.

For investors, one question that needs to be answered is what happens when the “pig finally exits the python.”

The Pig Exits The Python

Investors are currently clinging from one economic headline, or Fed comment, to the next in hopes of a sign the Fed will restart monetary accommodation. However, the Federal Reserve remains adamant that inflation is the more significant concern and that some “economic pain” may be needed.

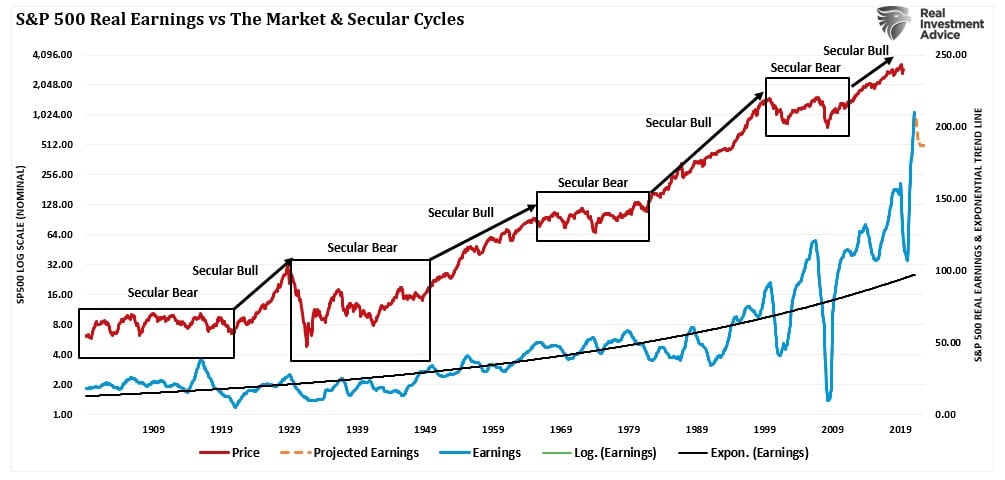

As noted, earnings are currently highly elevated due to the massive fiscal interventions that dragged forward consumption. We previously discussed that earnings are extremely deviated above their long-term growth trends and well above what the economy can naturally generate.

“The problem of overvaluation in a slow-growth economic environment is problematic. The massive surge in earnings during the pandemic-driven shutdown is unsustainable as the economy normalizes. Massive stimulus programs, combined with enormous unemployment, led to surging profits that are not replicable in the future. As shown, earnings are one of the most mean-reverting data series in existence, and ultimately if earnings don’t revert, capitalism is no longer functioning correctly.”

Earnings can not, over the long term, outgrow the economy. Such is because it is economic activity that creates corporate revenues. As the lag effect of monetary tightening bits into economic growth, both economic growth and corporate earnings must revert to historical norms. Such suggests that asset prices are vulnerable to significant repricing to reflect future economic realities. The outcome seems inevitable without either the Federal Reserve reverting to quantitative easing or the Government injecting more fiscal stimulus.

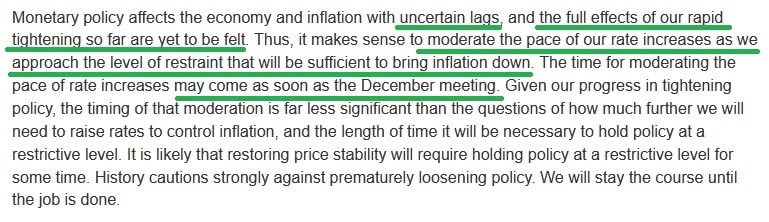

Jerome Powell’s recent statement from the Brookings Institution speech was full of warnings about the lag effect of monetary policy changes. It was also clear there is no “pivot” in policy coming anytime soon.

Investors should remain cautious as the “pig exits the python” over the next several months. The consequence must be that markets adjust to a world with less monetary accommodation. In such an environment, accelerated returns will no longer be possible.